Why America misses its icon Harry Dean Stanton

His last film, 'Lucky', completed six months before his death, echoes the actor's own incredible life

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Marlon Brando used to telephone his friend Harry Dean Stanton late at night in the 1970s to chat about acting. “He taught me Shakespearean monologues from The Tempest and Macbeth,” recalled Stanton.

Stanton’s favourite soliloquy was Macbeth’s one about life being “a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing,” which Stanton would recite to friends and strangers and follow by saying: “Great line, eh?”

The meaning of life and death, and whether existence is anything more than a “black void”, is also at the heart of Stanton’s final movie, Lucky, which he completed just six months before he died at the age of 91 on 15 September 2017.

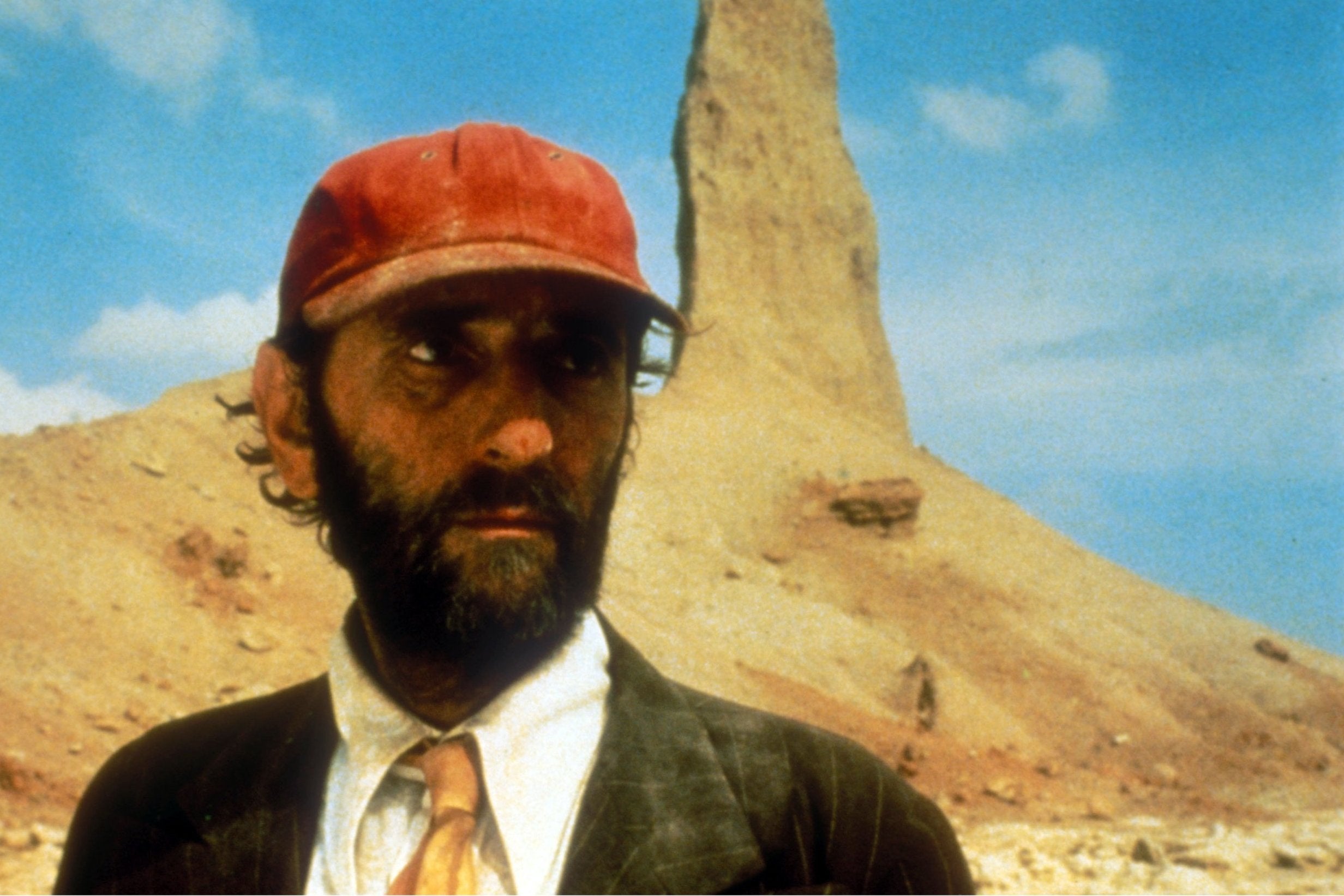

In Lucky, which marks John Carroll Lynch’s directorial debut, he plays a loner called Lucky in a small Californian desert town who is meditating on his past and his own mortality. The character echoes Stanton’s own life, with scriptwriters Logan Sparks and Drago Sumonja drawing on the experiences of one of the most remarkable actors of modern times.

Lucky explains that his name comes from his time in the Second World War when he served aboard USS Landing Ship Tank (LST) 970, as did Stanton himself. “I was in the battle of Okinawa,” the actor recalled. “People who are actors now don’t have that kind of life experience; I saw action on a ship. I was damn lucky I didn’t get blown up or killed.”

Stanton had got the job after the intervention of a career sailor uncle, who told him the safest job in the navy was as a cook on a supply ship. What neither knew was that the vessel was hauling big shells for battleships and was a constant target for Japanese bombers. Sparks, who was Stanton’s close friend for more than a decade and who was also the film’s co-producer, tells me: “Harry said it was always scary because when those LST’s were hit they would go up like a Roman candle.”

The experience gave the actor a lasting knowledge of the fragility of life – not that concerns over longevity stopped him being a chain-smoker for seven decades. Brando once threatened to throw Stanton out of a window for lighting up a cigarette during a meal at an elegant restaurant. In a segment taken from real life, Lucky smokes even when he is doing his daily yoga exercises.

“Filming was a bitter-sweet time,” says Sparks. “Harry said that whatever happens this would be his last movie. He knew the scenes inside and out and would swim around in the lines until his fingers got pruney. He was enthralled with making the movie, but a lot of the topics upset him. He was really scared and he was also at peace. There was a strange duality.

“The last time I saw him at his house was about six months after the film had been made. He was sitting on his sofa and was really ill and coughing. He looked at me and said: ‘I’m scared.’ Then he tried to light a cigarette and when I said: ‘Those things will kill you,’ he said: ‘I hope it does.’ I knew it was the beginning of the end. He got an infection and died of congestive heart failure. I held his hand at the hospital when he passed away. I made a promise that I would be there to the end and I am really glad that I kept my promise.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Stanton’s last role is a fitting curtain call on a wonderful career. He said that “whatever psychological traumas or conflicts I’m going through I try to put into my roles”. This happens in Lucky in an exceptionally moving scene when Stanton shows his gift at evoking painful emotions through the sheer honesty of his performance.

His character phones a friend at night and confesses a memory that has haunted him all his life. “When I was a kid living in Kentucky I had this BB gun that didn’t shoot straight,” he says. “So I was out one day, shooting at things, trees, leaves, and there was a mockingbird up in a tree singing its heart out. And I aimed my gun just to scare him away, pulled the trigger, and the singing stopped … the silence it cast in the world was devastating.”

It is such a powerful monologue that I wondered whether it is true. “That was a real story that happened when Harry was a little boy,” says Sparks. “He told me about it a decade or so before and the story really shook me up. He said it was the saddest moment of his whole life.”

“Filming the mockingbird scene really affected him. I drove him to the set every morning and on the day the monologue was filmed, he said: ‘I don’t want to do that.’ I told him it was an opportunity to get it off his chest and share that pain with the world. He rode in silence for a while and then said: ‘Well, I’ll give it a shot.’ When he finished the scene, there wasn’t a dry eye in the house.”

Even as a young actor, Stanton’s appearance had its own unique character, a face that was able to channel harrowing emotions. That’s part of what made him so special. His face in Lucky is more grizzled and lean than in the celebrated Paris, Texas days of his late fifties, but those same distinctive hollow eyes are still transfixing.

Although those eyes radiate sadness, they also seem to say that if you lose all hope, you can always find it again. David Lynch, who stars in the film and directed Stanton in the TV show Twin Peaks, believes that “all actors will agree, no one gives a more honest, natural, truer performance than Harry Dean Stanton”.

Stanton made more than 200 films before Lucky, joking that the big break for a former navy man came in a debut filming an air force documentary. In the 1950s and 1960s he did the rounds of bit-part television roles and minor film characters, often playing cowboys, police officers or small-town losers and conmen. He was, however, particularly proud of a brief, uncredited, part in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1956 thriller The Wrong Man. “To put it mildly, I was just a very late bloomer,” he said.

He began to break out of obscurity in the late 1960s and went on to have impressive minor roles in some of the finest films of the late 20th century, including In the Heat of the Night, Cool Hand Luke, The Godfather Part II, Alien, One from the Heart and Repo Man.

During Lucky he would share memories of his past career and unsurprisingly one movie stood out. “The film he talked about most on the set was Paris, Texas,” says Sparks. This masterpiece came when Stanton was 58, and was finally and unexpectedly given a chance to be a leading man.

Director Wim Wenders, whose film went on to win the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, said: “Even when he did Paris, Texas, Harry was full of self-doubt, and we had to hold his hands every evening.” Stanton admitted that he was “shy” and that, even at such an advanced stage in his career, he was “a man who had an extreme lack of self-confidence”.

But this vulnerability helped him give the performance of a lifetime as Travis Henderson. He captured and conveyed the achingly painful emotions of a forlorn lost soul. Wenders believes it had a lot to do with his essential “innocence” as a person and how “he kept the child that’s dead in most adults”.

Travis is a wandering amnesiac who, seeking repentance, returns to the wife and son he left mysteriously four years before. The scene at the Keyhole Club, in which he talks to his wife Jane (Nastassja Kinski) through a one-way mirror, is one of the most heart-breaking in modern cinema.

Stanton was a master of pathos and knew what he was doing. “Paris, Texas gave me a chance to play compassion and I’m spelling that with a capital C,” he said. “I liked the writing, the cinematography, Ry Cooder’s scoring, and the casting, just all of it. It was the first lead I played, too. A romantic lead.”

Parts of Lucky are reminiscent of Paris, Texas. The images of Stanton walking through desert locations, and the sense of a man lost in the wilderness of nature as well as his own thoughts, was done intentionally.

“We wanted to do an homage,” says Sparks. “I have always thought that Paris, Texas is a very European film. It’s through the eyes of Americana but from a European perspective. Growing up in Arizona, you are used to the open spaces. The start of Lucky is like pieces of a mosaic, with his character basically being born from the desert.”

Stanton was born on 14 July 1926 in West Irvine, Kentucky. He said he imagined being an actor from the moment he walked out of a movie house as a child “thinking I was Humphrey Bogart”. In 1979 he played Asa Hawks in John Huston’s adaptation of the Flannery O’Connor’s novel Wise Blood in 1979.

As well as being a fan of O’Connor’s books, he was delighted to work with the director of the Bogart film Key Largo, which he had seen as a young man in 1948. “I worked with the best directors. Martin Scorsese, John Huston, David Lynch, Alfred Hitchcock,” he said in 2013.

His southern Baptist family upbringing was not a happy one, though. “My father and mother were not compatible. I don’t think they had a good wedding night and I was the product of that. We weren’t close.”

Stanton used to talk about his childhood with Sparks: “His mother was very aware of his success,” says Sparks. “His dad Sheridan was always called ‘Shorty’. He was a short little man. He was barber in West Irvine and Harry used to joke: ‘Well, if you think West Irvine is small, you should have seen East Irvine.’ His dad also worked as a tobacco farmer and Harry said he was a very serious man, from a different generation.”

Before his parents’ divorce, Stanton would sometimes escape their rows by listening to records. Music remained a true love throughout his life. After a spell studying radio journalism at the University of Kentucky, he answered a “singers wanted” advert in his local newspaper and then toured the country with a choral group, singing in department stores and town halls.

“I’ve always been a singer. I sang in high school, glee clubs; I was a soloist. I was singing when I was five years old. I had a lot of speech training and a lot of voice training and I was just blessed with a good voice and a good ear for music,” he said.

One of the reasons he had such fond memories of making Cool Hand Luke with Paul Newman was because “I got to sing in that one. I like to sing and it was fun.” In the 1967 movie he performs four songs, including a haunting version of the gospel tune “Just a Closer Walk with Thee”, which made fellow actress Jo Van Fleet weep.

The man from Kentucky loved nostalgic music, especially the traditional Mexican song “Canción Mixteca” – which he sings in Paris, Texas backed by Cooder on guitar. He once credited the guitar legend with getting him back playing music. “Ry was the one who got me singing as an adult. I’ve played all over America and even in Australia since then.”

He performed with Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Leon Russell and Willie Nelson. Kris Kristofferson and former girlfriend Debbie Harry have both written songs about him and in 2014 he released the album Harry Dean Stanton: Partly Fiction, which includes a fine version of “Hands on the Wheel”, a hit for Nelson.

Visitors to his home in the hills above Los Angeles would be struck by a doormat that said “Welcome UFOs and Crews”, a large photograph of a baby pinned on his fridge – not his own child, but that of guitarist friend Dave Stewart and Siobhan Fahley – and the impressive collection of musical instruments on the walls of the house. There were finely tuned acoustic and slide guitars, resonators, banjos and mandolins.

Stanton also performs music in Lucky – including playing “Red River Valley” on the harmonica and singing a touching version of “Volver, Volver” at a fiesta – and he sang at Sparks’s wedding, putting his own spin on Roy Orbison’s country music classic “Blue Bayou”.

“Harry used to say: ‘I was best man at Jack Nicholson’s first wedding ... and at his first divorce,’” recalls Sparks. “He was best man at my wedding in 2015, which was held in my backyard in north Hollywood. It was very unconventional.

“There was a marching band, a replica of the Doctor Who Tardis and my wife was seven months pregnant. As she walked down the aisle, barefoot in a red dress to the sounds of the Beach Boys song “Wouldn’t it Be Nice”, Harry stopped the ceremony and said: ‘This is the craziest shotgun wedding I have ever been to’. The place just erupted in laughter and we started again. He played the harmonica and sang “Blue Bayou” for our first married song.”

Stanton was famously good friends with Nicholson and the pair starred with Brando in Arthur Penn’s The Missouri Breaks in 1976. They partied so much after filming that they were told to leave the local motel. Stanton said he owed a lot to Nicholson’s advice that you have to behave on screen as you do in real life. They lived together in Laurel Canyon after Nicholson’s divorce in 1968 and played a lot of golf. Stanton said he was surprised to find he had “a real knack for the game”.

Much of Lucky is about longevity and Stanton’s life was full of lasting friendships, not least with Lynch. Stanton persuaded him to play Howard in the movie, a character who is pining for a lost tortoise called Roosevelt.

“Harry and David were best friends,” says Sparks. “Their relationship was great. David would come over to Harry’s house and they would watch game shows from the 1970s. Most of all they liked to get together and sit on Harry’s sofa, smoke cigarettes and not talk. Harry used to quote Charles Bukowski all the time about how your family can be shit but you can choose your friends.”

Stanton seems to have been a man of contradictions. He was someone who loved the History Channel, the literature of Gertrude Stein and ferociously competitive games of Scrabble. He was also a man content to while away hours watching game shows or Court TV.

He said he stopped playing poker because he lost hundreds of thousands of dollars. Maybe those sad eyes were too much of a giveaway for a weak hand? Sparks acknowledges a duel nature in the actor. “Harry was very compassionate and had a huge heart but he was also quick to say: ‘Hey, how about you go fuck yourself,’” he says.

There was genuine grief in Hollywood when Stanton died, from the many stars whose lives he had touched. Sean Penn called him “the gentlest, kindest, most ornery and philosophical old bastard any of us ever knew”. Randy Quaid’s brother, Dennis, who had been Stanton’s assistant on The Missouri Breaks, described him as “a lifetime mentor, friend and father-figure”.

Former lover Rebecca de Mornay, who met him as a 23-year-old when they were in the 1982 film One from the Heart, said they remained friends after splitting up and that she still looked back fondly on their early days. “He hit on me, and I was 33 years younger than him. He had a great pickup line: ‘Do you believe in magic?’”

As well as fellow actors, Stanton enjoyed a rapport with the public. “Part of the reason he was so powerful as an actor was that he was so real on screen,” says Sparks. “Ordinary people recognised things about him in their own lives. People related to him. Harry would be approached by people who told him that he reminded them of their dad.

“I heard many, many people come up and say because of him in Pretty in Pink they had a better relationship with their own father. He would also get lots of science-fiction fans telling him they liked him in Alien. He was one of the Americana icons that we don’t know what to do without now.”

In addition to all the films, Stanton had a long career in television, going back to Gunsmoke in the 1950s. One of his best TV roles was as Roman Grant in the HBO show Big Love, which ran from 2006 to 2011, and it was while working there that he met Sparks.

“I drove him for one day and we just hit it off. We became buddies,” Sparks says. “We had been in the car about 15 minutes, and he was smoking, and I clearly recall the very first thing he said to me. ‘Hey, can you remember where you were before you were born?’ he said suddenly. I said: ‘You know, I can’t.’ Harry paused and said: ‘Well, what makes you think there is something afterwards?’”

Logan Sparks will be appearing at the Curzon Soho on Saturday 15 September for a special post-screening discussion about Lucky – Details here. Lucky is screening in cinemas nationwide and On Demand. Book Tickets here

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments