Groundhog Day is 25 years old but fittingly eternal

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.How should one live? What should one live for? Hedonism? Knowledge? Charity? Experience? Love? Is it even possible to extricate these from one another?

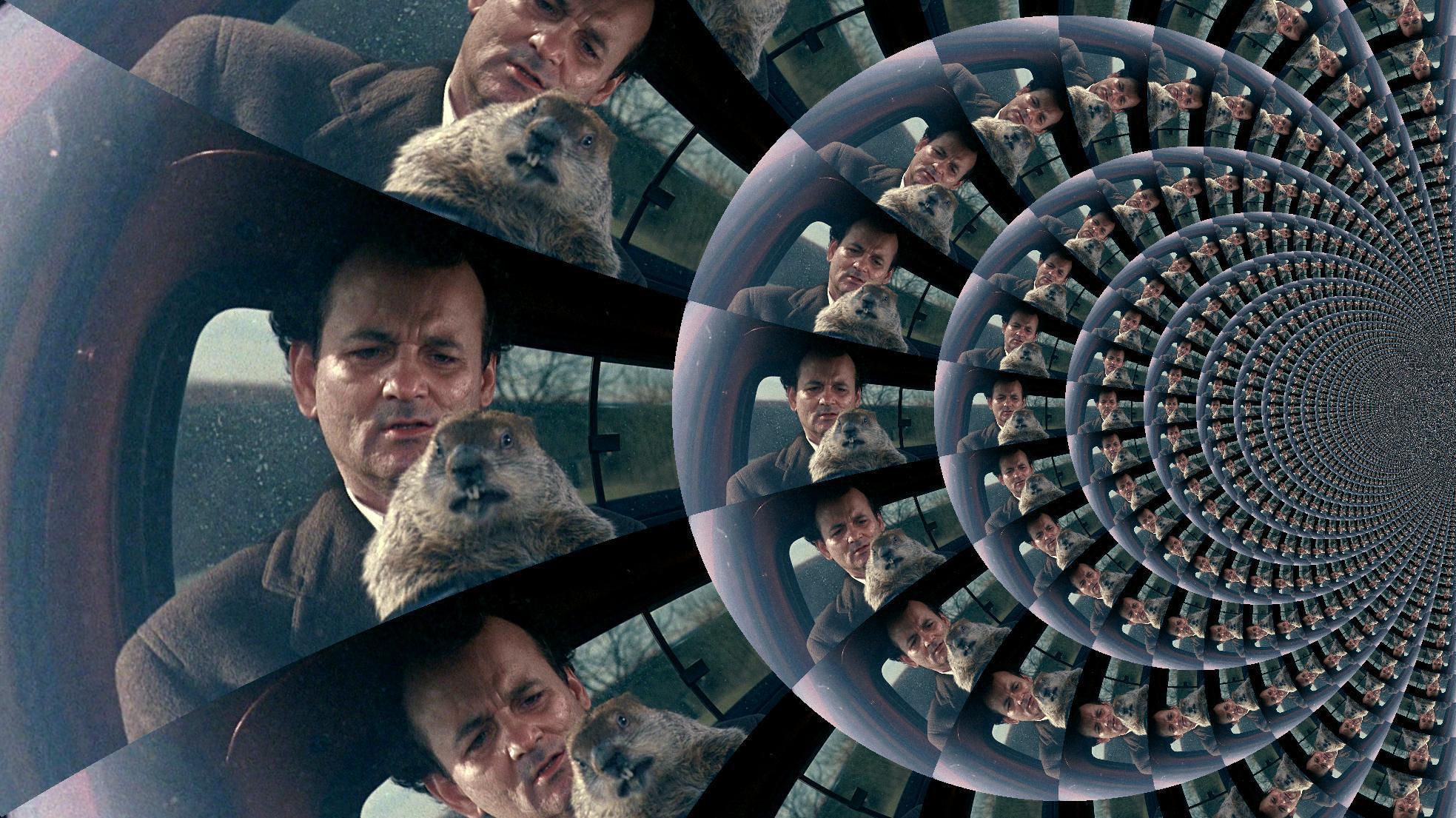

An endless, perpetual playground, albeit a dreary, small-town Pennsylvania one, is the perfect place to explore these concepts, an intellectual exercise of the greatest significance; for Heidegger, the question of eternal recurrence was the “most burdensome thought”, perhaps the “thought of thoughts”. And yet, Harold Ramis’ Groundhog Day, which turns 25 this month, never struggles under the weight of this philosophical heft, nor does it particularly regard it – it’s almost happenstance.

“I never intended it to be anything more than a good, heartfelt, entertaining story,” Ramis once said, and this is what makes the film so successful. Groundhog Day stays resolutely romcom and refuses to get bogged down in analysis of Phil Connors’ days in Punxsutawney (37 of which are seen on screen, though the entirety of his purgatory could be anywhere between 30 years (Ramis’ revised estimate) to 10,000 years (amount of time it takes for the soul to evolve to the next level according to Buddhist doctrine), something it’s hard to imagine happening had the film been made today, when philosophical ruminations in voiceover often prove irresistible to filmmakers.

Though the film might feel effortless, it was not. Bill Murray and Ramis would end up not speaking for nearly 20 years after quibbles with the script, which was the subject of several would-be catastrophic changes long before Murray was even in the mix (the role was first offered to Tom Hanks and Michael Keaton).

Initially, screenwriter Danny Rubin wanted to include voiceover narration from Phil, which might have over-explained his mental state that we’re otherwise left to imagine ourselves. Worse, the studio wanted Rubin to make the film more conventional, leading him to acquiesce and submit a new draft in which there was an explanation for Phil being trapped in time – some ghastly plot device involving a scorned girlfriend casting a spell, which Rubin insisted would “take away everything that was innovative and interesting and turn it into an easily-dismissed Hollywood comedy”. There was also talk of, in the third act, giving Phil a sense that he might be able to close the time loop, which presumably would have precipitated an Inception-esque, plot-driven ending.

But Ramis steadied the course and the film stayed playfully simple, having the same kind of shrugging demeanour as the man at the centre of it. The love story shouldn’t work, Murray being so deadpan and non-emotive while Andie McDowell (Rita) dials up the schmaltz, but this ultimately serves to make regular life seem artificial, dreamlike and saccharine, reinforcing Phil’s profound sense of misery and exhaustion amongst it.

The film refuses to date, and different days in Phil’s long life stand out with each repeat viewing, my favourite being the stretch when, having successfully seduced Rita, he tries to do it again on autopilot each day, these scenes bringing to mind the forced conviviality and regurgitated anecdotes of a 58th Tinder date.

A perfectly-balanced movie, Groundhog Day is never taxing, a light, warm film and an “easy watch”, in spite of its propensity to ask big questions like:

How should one live? What should one live for? Hedonism? Knowledge? Charity? Experience? Love? Is it even possible to extricate these from one another?

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

An endless, perpetual playground, albeit a dreary, small-town Pennsylvania one, is the perfect place to explore these concepts, an intellectual exercise of the greatest significance; for Heidegger, the question of eternal recurrence was the “most burdensome thought”, perhaps the “thought of thoughts”. And yet, Harold Ramis’ Groundhog Day, which turns 25 this month, never struggles under the weight of this philosophical heft, nor does it particularly regard it – it’s almost happenstance.

“I never intended it to be anything more than a good, heartfelt, entertaining story,” Ramis once said, and this is what makes the film so successful. Groundhog Day stays resolutely romcom and refuses to get bogged down in analysis of Phil Connors’ days in Punxsutawney (37 of which are seen on screen, though the entirety of his purgatory could be anywhere between 30 years (Ramis’ revised estimate) to 10,000 years (amount of time it takes for the soul to evolve to the next level according to Buddhist doctrine), something it’s hard to imagine happening had the film been made today, when philosophical ruminations in voiceover often prove irresistible to filmmakers.

Though the film might feel effortless, it was not. Bill Murray and Ramis would end up not speaking for nearly 20 years after quibbles with the script, which was the subject of several would-be catastrophic changes long before Murray was even in the mix (the role was first offered to Tom Hanks and Michael Keaton).

Initially, screenwriter Danny Rubin wanted to include voiceover narration from Phil, which might have over-explained his mental state that we’re otherwise left to imagine ourselves. Worse, the studio wanted Rubin to make the film more conventional, leading him to acquiesce and submit a new draft in which there was an explanation for Phil being trapped in time – some ghastly plot device involving a scorned girlfriend casting a spell, which Rubin insisted would “take away everything that was innovative and interesting and turn it into an easily-dismissed Hollywood comedy”. There was also talk of, in the third act, giving Phil a sense that he might be able to close the time loop, which presumably would have precipitated an Inception-esque, plot-driven ending.

But Ramis steadied the course and the film stayed playfully simple, having the same kind of shrugging demeanour as the man at the centre of it. The love story shouldn’t work, Murray being so deadpan and non-emotive while Andie McDowell (Rita) dials up the schmaltz, but this ultimately serves to make regular life seem artificial, dreamlike and saccharine, reinforcing Phil’s profound sense of misery and exhaustion amongst it.

The film refuses to date, and different days in Phil’s long life stand out with each repeat viewing, my favourite being the stretch when, having successfully seduced Rita, he tries to do it again on autopilot each day, these scenes bringing to mind the forced conviviality and regurgitated anecdotes of a 58th Tinder date.

A perfectly-balanced movie, Groundhog Day is never taxing, a light, warm film and an “easy watch”, in spite of its propensity to ask big questions like:

How should one live? What should one live for? Hedonism? Knowledge? Charity? Experience? Love? Is it even possible to extricate these from one another?

An endless, perpetual playground, albeit a dreary, small-town Pennsylvania one, is the perfect place to explore these concepts, an intellectual exercise of the greatest significance; for Heidegger, the question of eternal recurrence was the “most burdensome thought”, perhaps the “thought of thoughts”. And yet, Harold Ramis’ Groundhog Day, which turns 25 this month, never struggles under the weight of this philosophical heft, nor does it particularly regard it – it’s almost happenstance.

“I never intended it to be anything more than a good, heartfelt, entertaining story,” Ramis once said, and this is what makes the film so successful. Groundhog Day stays resolutely romcom and refuses to get bogged down in analysis of Phil Connors’ days in Punxsutawney (37 of which are seen on screen, though the entirety of his purgatory could be anywhere between 30 years (Ramis’ revised estimate) to 10,000 years (amount of time it takes for the soul to evolve to the next level according to Buddhist doctrine), something it’s hard to imagine happening had the film been made today, when philosophical ruminations in voiceover often prove irresistible to filmmakers.

Though the film might feel effortless, it was not. Bill Murray and Ramis would end up not speaking for nearly 20 years after quibbles with the script, which was the subject of several would-be catastrophic changes long before Murray was even in the mix (the role was first offered to Tom Hanks and Michael Keaton).

Initially, screenwriter Danny Rubin wanted to include voiceover narration from Phil, which might have over-explained his mental state that we’re otherwise left to imagine ourselves. Worse, the studio wanted Rubin to make the film more conventional, leading him to acquiesce and submit a new draft in which there was an explanation for Phil being trapped in time – some ghastly plot device involving a scorned girlfriend casting a spell, which Rubin insisted would “take away everything that was innovative and interesting and turn it into an easily-dismissed Hollywood comedy”. There was also talk of, in the third act, giving Phil a sense that he might be able to close the time loop, which presumably would have precipitated an Inception-esque, plot-driven ending.

But Ramis steadied the course and the film stayed playfully simple, having the same kind of shrugging demeanour as the man at the centre of it. The love story shouldn’t work, Murray being so deadpan and non-emotive while Andie McDowell (Rita) dials up the schmaltz, but this ultimately serves to make regular life seem artificial, dreamlike and saccharine, reinforcing Phil’s profound sense of misery and exhaustion amongst it.

The film refuses to date, and different days in Phil’s long life stand out with each repeat viewing, my favourite being the stretch when, having successfully seduced Rita, he tries to do it again on autopilot each day, these scenes bringing to mind the forced conviviality and regurgitated anecdotes of a 58th Tinder date.

A perfectly-balanced movie, Groundhog Day is never taxing, a light, warm film and an “easy watch”, in spite of its propensity to ask big questions like:

How should one live? What should one live for? Hedonism? Knowledge? Charity? Experience? Love? Is it even possible to extricate these from one another?

An endless, perpetual playground, albeit a dreary, small-town Pennsylvania one, is the perfect place to explore these concepts, an intellectual exercise of the greatest significance; for Heidegger, the question of eternal recurrence was the “most burdensome thought”, perhaps the “thought of thoughts”. And yet, Harold Ramis’ Groundhog Day, which turns 25 this month, never struggles under the weight of this philosophical heft, nor does it particularly regard it – it’s almost happenstance.

“I never intended it to be anything more than a good, heartfelt, entertaining story,” Ramis once said, and this is what makes the film so successful. Groundhog Day stays resolutely romcom and refuses to get bogged down in analysis of Phil Connors’ days in Punxsutawney (37 of which are seen on screen, though the entirety of his purgatory could be anywhere between 30 years (Ramis’ revised estimate) to 10,000 years (amount of time it takes for the soul to evolve to the next level according to Buddhist doctrine), something it’s hard to imagine happening had the film been made today, when philosophical ruminations in voiceover often prove irresistible to filmmakers.

Though the film might feel effortless, it was not. Bill Murray and Ramis would end up not speaking for nearly 20 years after quibbles with the script, which was the subject of several would-be catastrophic changes long before Murray was even in the mix (the role was first offered to Tom Hanks and Michael Keaton).

Initially, screenwriter Danny Rubin wanted to include voiceover narration from Phil, which might have over-explained his mental state that we’re otherwise left to imagine ourselves. Worse, the studio wanted Rubin to make the film more conventional, leading him to acquiesce and submit a new draft in which there was an explanation for Phil being trapped in time – some ghastly plot device involving a scorned girlfriend casting a spell, which Rubin insisted would “take away everything that was innovative and interesting and turn it into an easily-dismissed Hollywood comedy”. There was also talk of, in the third act, giving Phil a sense that he might be able to close the time loop, which presumably would have precipitated an Inception-esque, plot-driven ending.

But Ramis steadied the course and the film stayed playfully simple, having the same kind of shrugging demeanour as the man at the centre of it. The love story shouldn’t work, Murray being so deadpan and non-emotive while Andie McDowell (Rita) dials up the schmaltz, but this ultimately serves to make regular life seem artificial, dreamlike and saccharine, reinforcing Phil’s profound sense of misery and exhaustion amongst it.

The film refuses to date, and different days in Phil’s long life stand out with each repeat viewing, my favourite being the stretch when, having successfully seduced Rita, he tries to do it again on autopilot each day, these scenes bringing to mind the forced conviviality and regurgitated anecdotes of a 58th Tinder date.

A perfectly-balanced movie, Groundhog Day is never taxing, a light, warm film and an “easy watch”, in spite of its propensity to ask big questions like:

How should one live? What should one live for? Hedonism? Knowledge? Charity? Experience? Love? Is it even possible to extricate these from one another?

An endless, perpetual playground, albeit a dreary, small-town Pennsylvania one, is the perfect place to explore these concepts, an intellectual exercise of the greatest significance; for Heidegger, the question of eternal recurrence was the “most burdensome thought”, perhaps the “thought of thoughts”. And yet, Harold Ramis’ Groundhog Day, which turns 25 this month, never struggles under the weight of this philosophical heft, nor does it particularly regard it – it’s almost happenstance.

“I never intended it to be anything more than a good, heartfelt, entertaining story,” Ramis once said, and this is what makes the film so successful. Groundhog Day stays resolutely romcom and refuses to get bogged down in analysis of Phil Connors’ days in Punxsutawney (37 of which are seen on screen, though the entirety of his purgatory could be anywhere between 30 years (Ramis’ revised estimate) to 10,000 years (amount of time it takes for the soul to evolve to the next level according to Buddhist doctrine), something it’s hard to imagine happening had the film been made today, when philosophical ruminations in voiceover often prove irresistible to filmmakers.

Though the film might feel effortless, it was not. Bill Murray and Ramis would end up not speaking for nearly 20 years after quibbles with the script, which was the subject of several would-be catastrophic changes long before Murray was even in the mix (the role was first offered to Tom Hanks and Michael Keaton).

Initially, screenwriter Danny Rubin wanted to include voiceover narration from Phil, which might have over-explained his mental state that we’re otherwise left to imagine ourselves. Worse, the studio wanted Rubin to make the film more conventional, leading him to acquiesce and submit a new draft in which there was an explanation for Phil being trapped in time – some ghastly plot device involving a scorned girlfriend casting a spell, which Rubin insisted would “take away everything that was innovative and interesting and turn it into an easily-dismissed Hollywood comedy”. There was also talk of, in the third act, giving Phil a sense that he might be able to close the time loop, which presumably would have precipitated an Inception-esque, plot-driven ending.

But Ramis steadied the course and the film stayed playfully simple, having the same kind of shrugging demeanour as the man at the centre of it. The love story shouldn’t work, Murray being so deadpan and non-emotive while Andie McDowell (Rita) dials up the schmaltz, but this ultimately serves to make regular life seem artificial, dreamlike and saccharine, reinforcing Phil’s profound sense of misery and exhaustion amongst it.

The film refuses to date, and different days in Phil’s long life stand out with each repeat viewing, my favourite being the stretch when, having successfully seduced Rita, he tries to do it again on autopilot each day, these scenes bringing to mind the forced conviviality and regurgitated anecdotes of a 58th Tinder date.

A perfectly-balanced movie, Groundhog Day is never taxing, a light, warm film and an “easy watch”, in spite of its propensity to ask big questions like:

How should one live? What should one live for? Hedonism? Knowledge? Charity? Experience? Love? Is it even possible to extricate these from one another?

An endless, perpetual playground, albeit a dreary, small-town Pennsylvania one, is the perfect place to explore these concepts, an intellectual exercise of the greatest significance; for Heidegger, the question of eternal recurrence was the “most burdensome thought”, perhaps the “thought of thoughts”. And yet, Harold Ramis’ Groundhog Day, which turns 25 this month, never struggles under the weight of this philosophical heft, nor does it particularly regard it – it’s almost happenstance.

“I never intended it to be anything more than a good, heartfelt, entertaining story,” Ramis once said, and this is what makes the film so successful. Groundhog Day stays resolutely romcom and refuses to get bogged down in analysis of Phil Connors’ days in Punxsutawney (37 of which are seen on screen, though the entirety of his purgatory could be anywhere between 30 years (Ramis’ revised estimate) to 10,000 years (amount of time it takes for the soul to evolve to the next level according to Buddhist doctrine), something it’s hard to imagine happening had the film been made today, when philosophical ruminations in voiceover often prove irresistible to filmmakers.

Though the film might feel effortless, it was not. Bill Murray and Ramis would end up not speaking for nearly 20 years after quibbles with the script, which was the subject of several would-be catastrophic changes long before Murray was even in the mix (the role was first offered to Tom Hanks and Michael Keaton).

Initially, screenwriter Danny Rubin wanted to include voiceover narration from Phil, which might have over-explained his mental state that we’re otherwise left to imagine ourselves. Worse, the studio wanted Rubin to make the film more conventional, leading him to acquiesce and submit a new draft in which there was an explanation for Phil being trapped in time – some ghastly plot device involving a scorned girlfriend casting a spell, which Rubin insisted would “take away everything that was innovative and interesting and turn it into an easily-dismissed Hollywood comedy”. There was also talk of, in the third act, giving Phil a sense that he might be able to close the time loop, which presumably would have precipitated an Inception-esque, plot-driven ending.

But Ramis steadied the course and the film stayed playfully simple, having the same kind of shrugging demeanour as the man at the centre of it. The love story shouldn’t work, Murray being so deadpan and non-emotive while Andie McDowell (Rita) dials up the schmaltz, but this ultimately serves to make regular life seem artificial, dreamlike and saccharine, reinforcing Phil’s profound sense of misery and exhaustion amongst it.

The film refuses to date, and different days in Phil’s long life stand out with each repeat viewing, my favourite being the stretch when, having successfully seduced Rita, he tries to do it again on autopilot each day, these scenes bringing to mind the forced conviviality and regurgitated anecdotes of a 58th Tinder date.

A perfectly-balanced movie, Groundhog Day is never taxing, a light, warm film and an “easy watch”, in spite of its propensity to ask big questions like:

How should one live? What should one live for? Hedonism? Knowledge? Charity? Experience? Love? Is it even possible to extricate these from one another?

An endless, perpetual playground, albeit a dreary, small-town Pennsylvania one, is the perfect place to explore these concepts, an intellectual exercise of the greatest significance; for Heidegger, the question of eternal recurrence was the “most burdensome thought”, perhaps the “thought of thoughts”. And yet, Harold Ramis’ Groundhog Day, which turns 25 this month, never struggles under the weight of this philosophical heft, nor does it particularly regard it – it’s almost happenstance.

“I never intended it to be anything more than a good, heartfelt, entertaining story,” Ramis once said, and this is what makes the film so successful. Groundhog Day stays resolutely romcom and refuses to get bogged down in analysis of Phil Connors’ days in Punxsutawney (37 of which are seen on screen, though the entirety of his purgatory could be anywhere between 30 years (Ramis’ revised estimate) to 10,000 years (amount of time it takes for the soul to evolve to the next level according to Buddhist doctrine), something it’s hard to imagine happening had the film been made today, when philosophical ruminations in voiceover often prove irresistible to filmmakers.

Though the film might feel effortless, it was not. Bill Murray and Ramis would end up not speaking for nearly 20 years after quibbles with the script, which was the subject of several would-be catastrophic changes long before Murray was even in the mix (the role was first offered to Tom Hanks and Michael Keaton).

Initially, screenwriter Danny Rubin wanted to include voiceover narration from Phil, which might have over-explained his mental state that we’re otherwise left to imagine ourselves. Worse, the studio wanted Rubin to make the film more conventional, leading him to acquiesce and submit a new draft in which there was an explanation for Phil being trapped in time – some ghastly plot device involving a scorned girlfriend casting a spell, which Rubin insisted would “take away everything that was innovative and interesting and turn it into an easily-dismissed Hollywood comedy”. There was also talk of, in the third act, giving Phil a sense that he might be able to close the time loop, which presumably would have precipitated an Inception-esque, plot-driven ending.

But Ramis steadied the course and the film stayed playfully simple, having the same kind of shrugging demeanour as the man at the centre of it. The love story shouldn’t work, Murray being so deadpan and non-emotive while Andie McDowell (Rita) dials up the schmaltz, but this ultimately serves to make regular life seem artificial, dreamlike and saccharine, reinforcing Phil’s profound sense of misery and exhaustion amongst it.

The film refuses to date, and different days in Phil’s long life stand out with each repeat viewing, my favourite being the stretch when, having successfully seduced Rita, he tries to do it again on autopilot each day, these scenes bringing to mind the forced conviviality and regurgitated anecdotes of a 58th Tinder date.

A perfectly-balanced movie, Groundhog Day is never taxing, a light, warm film and an “easy watch”, in spite of its propensity to ask big questions like:

How should one live? What should one live for? Hedonism? Knowledge? Charity? Experience? Love? Is it even possible to extricate these from one another?

An endless, perpetual playground, albeit a dreary, small-town Pennsylvania one, is the perfect place to explore these concepts, an intellectual exercise of the greatest significance; for Heidegger, the question of eternal recurrence was the “most burdensome thought”, perhaps the “thought of thoughts”. And yet, Harold Ramis’ Groundhog Day, which turns 25 this month, never struggles under the weight of this philosophical heft, nor does it particularly regard it – it’s almost happenstance.

“I never intended it to be anything more than a good, heartfelt, entertaining story,” Ramis once said, and this is what makes the film so successful. Groundhog Day stays resolutely romcom and refuses to get bogged down in analysis of Phil Connors’ days in Punxsutawney (37 of which are seen on screen, though the entirety of his purgatory could be anywhere between 30 years (Ramis’ revised estimate) to 10,000 years (amount of time it takes for the soul to evolve to the next level according to Buddhist doctrine), something it’s hard to imagine happening had the film been made today, when philosophical ruminations in voiceover often prove irresistible to filmmakers.

Though the film might feel effortless, it was not. Bill Murray and Ramis would end up not speaking for nearly 20 years after quibbles with the script, which was the subject of several would-be catastrophic changes long before Murray was even in the mix (the role was first offered to Tom Hanks and Michael Keaton).

Initially, screenwriter Danny Rubin wanted to include voiceover narration from Phil, which might have over-explained his mental state that we’re otherwise left to imagine ourselves. Worse, the studio wanted Rubin to make the film more conventional, leading him to acquiesce and submit a new draft in which there was an explanation for Phil being trapped in time – some ghastly plot device involving a scorned girlfriend casting a spell, which Rubin insisted would “take away everything that was innovative and interesting and turn it into an easily-dismissed Hollywood comedy”. There was also talk of, in the third act, giving Phil a sense that he might be able to close the time loop, which presumably would have precipitated an Inception-esque, plot-driven ending.

But Ramis steadied the course and the film stayed playfully simple, having the same kind of shrugging demeanour as the man at the centre of it. The love story shouldn’t work, Murray being so deadpan and non-emotive while Andie McDowell (Rita) dials up the schmaltz, but this ultimately serves to make regular life seem artificial, dreamlike and saccharine, reinforcing Phil’s profound sense of misery and exhaustion amongst it.

The film refuses to date, and different days in Phil’s long life stand out with each repeat viewing, my favourite being the stretch when, having successfully seduced Rita, he tries to do it again on autopilot each day, these scenes bringing to mind the forced conviviality and regurgitated anecdotes of a 58th Tinder date.

A perfectly-balanced movie, Groundhog Day is never taxing, a light, warm film and an “easy watch”, in spite of its propensity to ask big questions like:

How should one live? What should one live for? Hedonism? Knowledge? Charity? Experience? Love? Is it even possible to extricate these from one another?

An endless, perpetual playground, albeit a dreary, small-town Pennsylvania one, is the perfect place to explore these concepts, an intellectual exercise of the greatest significance; for Heidegger, the question of eternal recurrence was the “most burdensome thought”, perhaps the “thought of thoughts”. And yet, Harold Ramis’ Groundhog Day, which turns 25 this month, never struggles under the weight of this philosophical heft, nor does it particularly regard it – it’s almost happenstance.

“I never intended it to be anything more than a good, heartfelt, entertaining story,” Ramis once said, and this is what makes the film so successful. Groundhog Day stays resolutely romcom and refuses to get bogged down in analysis of Phil Connors’ days in Punxsutawney (37 of which are seen on screen, though the entirety of his purgatory could be anywhere between 30 years (Ramis’ revised estimate) to 10,000 years (amount of time it takes for the soul to evolve to the next level according to Buddhist doctrine), something it’s hard to imagine happening had the film been made today, when philosophical ruminations in voiceover often prove irresistible to filmmakers.

Though the film might feel effortless, it was not. Bill Murray and Ramis would end up not speaking for nearly 20 years after quibbles with the script, which was the subject of several would-be catastrophic changes long before Murray was even in the mix (the role was first offered to Tom Hanks and Michael Keaton).

Initially, screenwriter Danny Rubin wanted to include voiceover narration from Phil, which might have over-explained his mental state that we’re otherwise left to imagine ourselves. Worse, the studio wanted Rubin to make the film more conventional, leading him to acquiesce and submit a new draft in which there was an explanation for Phil being trapped in time – some ghastly plot device involving a scorned girlfriend casting a spell, which Rubin insisted would “take away everything that was innovative and interesting and turn it into an easily-dismissed Hollywood comedy”. There was also talk of, in the third act, giving Phil a sense that he might be able to close the time loop, which presumably would have precipitated an Inception-esque, plot-driven ending.

But Ramis steadied the course and the film stayed playfully simple, having the same kind of shrugging demeanour as the man at the centre of it. The love story shouldn’t work, Murray being so deadpan and non-emotive while Andie McDowell (Rita) dials up the schmaltz, but this ultimately serves to make regular life seem artificial, dreamlike and saccharine, reinforcing Phil’s profound sense of misery and exhaustion amongst it.

The film refuses to date, and different days in Phil’s long life stand out with each repeat viewing, my favourite being the stretch when, having successfully seduced Rita, he tries to do it again on autopilot each day, these scenes bringing to mind the forced conviviality and regurgitated anecdotes of a 58th Tinder date.

A perfectly-balanced movie, Groundhog Day is never taxing, a light, warm film and an “easy watch”, in spite of its propensity to ask big questions like:

How should one live? What should one live for? Hedonism? Knowledge? Charity? Experience? Love? Is it even possible to extricate these from one another?

An endless, perpetual playground, albeit a dreary, small-town Pennsylvania one, is the perfect place to explore these concepts, an intellectual exercise of the greatest significance; for Heidegger, the question of eternal recurrence was the “most burdensome thought”, perhaps the “thought of thoughts”. And yet, Harold Ramis’ Groundhog Day, which turns 25 this month, never struggles under the weight of this philosophical heft, nor does it particularly regard it – it’s almost happenstance.

“I never intended it to be anything more than a good, heartfelt, entertaining story,” Ramis once said, and this is what makes the film so successful. Groundhog Day stays resolutely romcom and refuses to get bogged down in analysis of Phil Connors’ days in Punxsutawney (37 of which are seen on screen, though the entirety of his purgatory could be anywhere between 30 years (Ramis’ revised estimate) to 10,000 years (amount of time it takes for the soul to evolve to the next level according to Buddhist doctrine), something it’s hard to imagine happening had the film been made today, when philosophical ruminations in voiceover often prove irresistible to filmmakers.

Though the film might feel effortless, it was not. Bill Murray and Ramis would end up not speaking for nearly 20 years after quibbles with the script, which was the subject of several would-be catastrophic changes long before Murray was even in the mix (the role was first offered to Tom Hanks and Michael Keaton).

Initially, screenwriter Danny Rubin wanted to include voiceover narration from Phil, which might have over-explained his mental state that we’re otherwise left to imagine ourselves. Worse, the studio wanted Rubin to make the film more conventional, leading him to acquiesce and submit a new draft in which there was an explanation for Phil being trapped in time – some ghastly plot device involving a scorned girlfriend casting a spell, which Rubin insisted would “take away everything that was innovative and interesting and turn it into an easily-dismissed Hollywood comedy”. There was also talk of, in the third act, giving Phil a sense that he might be able to close the time loop, which presumably would have precipitated an Inception-esque, plot-driven ending.

But Ramis steadied the course and the film stayed playfully simple, having the same kind of shrugging demeanour as the man at the centre of it. The love story shouldn’t work, Murray being so deadpan and non-emotive while Andie McDowell (Rita) dials up the schmaltz, but this ultimately serves to make regular life seem artificial, dreamlike and saccharine, reinforcing Phil’s profound sense of misery and exhaustion amongst it.

The film refuses to date, and different days in Phil’s long life stand out with each repeat viewing, my favourite being the stretch when, having successfully seduced Rita, he tries to do it again on autopilot each day, these scenes bringing to mind the forced conviviality and regurgitated anecdotes of a 58th Tinder date.

A perfectly-balanced movie, Groundhog Day is never taxing, a light, warm film and an “easy watch”, in spite of its propensity to ask big questions like:

How should one live? What should one live for? Hedonism? Knowledge? Charity? Experience? Love? Is it even possible to extricate these from one another?

An endless, perpetual playground, albeit a dreary, small-town Pennsylvania one, is the perfect place to explore these concepts, an intellectual exercise of the greatest significance; for Heidegger, the question of eternal recurrence was the “most burdensome thought”, perhaps the “thought of thoughts”. And yet, Harold Ramis’ Groundhog Day, which turns 25 this month, never struggles under the weight of this philosophical heft, nor does it particularly regard it – it’s almost happenstance.

“I never intended it to be anything more than a good, heartfelt, entertaining story,” Ramis once said, and this is what makes the film so successful. Groundhog Day stays resolutely romcom and refuses to get bogged down in analysis of Phil Connors’ days in Punxsutawney (37 of which are seen on screen, though the entirety of his purgatory could be anywhere between 30 years (Ramis’ revised estimate) to 10,000 years (amount of time it takes for the soul to evolve to the next level according to Buddhist doctrine), something it’s hard to imagine happening had the film been made today, when philosophical ruminations in voiceover often prove irresistible to filmmakers.

Though the film might feel effortless, it was not. Bill Murray and Ramis would end up not speaking for nearly 20 years after quibbles with the script, which was the subject of several would-be catastrophic changes long before Murray was even in the mix (the role was first offered to Tom Hanks and Michael Keaton).

Initially, screenwriter Danny Rubin wanted to include voiceover narration from Phil, which might have over-explained his mental state that we’re otherwise left to imagine ourselves. Worse, the studio wanted Rubin to make the film more conventional, leading him to acquiesce and submit a new draft in which there was an explanation for Phil being trapped in time – some ghastly plot device involving a scorned girlfriend casting a spell, which Rubin insisted would “take away everything that was innovative and interesting and turn it into an easily-dismissed Hollywood comedy”. There was also talk of, in the third act, giving Phil a sense that he might be able to close the time loop, which presumably would have precipitated an Inception-esque, plot-driven ending.

But Ramis steadied the course and the film stayed playfully simple, having the same kind of shrugging demeanour as the man at the centre of it. The love story shouldn’t work, Murray being so deadpan and non-emotive while Andie McDowell (Rita) dials up the schmaltz, but this ultimately serves to make regular life seem artificial, dreamlike and saccharine, reinforcing Phil’s profound sense of misery and exhaustion amongst it.

The film refuses to date, and different days in Phil’s long life stand out with each repeat viewing, my favourite being the stretch when, having successfully seduced Rita, he tries to do it again on autopilot each day, these scenes bringing to mind the forced conviviality and regurgitated anecdotes of a 58th Tinder date.

A perfectly-balanced movie, Groundhog Day is never taxing, a light, warm film and an “easy watch”, in spite of its propensity to ask big questions like:

How should one live? What should one live for? Hedonism? Knowledge? Charity? Experience? Love? Is it even possible to extricate these from one another?

An endless, perpetual playground, albeit a dreary, small-town Pennsylvania one, is the perfect place to explore these concepts, an intellectual exercise of the greatest significance; for Heidegger, the question of eternal recurrence was the “most burdensome thought”, perhaps the “thought of thoughts”. And yet, Harold Ramis’ Groundhog Day, which turns 25 this month, never struggles under the weight of this philosophical heft, nor does it particularly regard it – it’s almost happenstance.

“I never intended it to be anything more than a good, heartfelt, entertaining story,” Ramis once said, and this is what makes the film so successful. Groundhog Day stays resolutely romcom and refuses to get bogged down in analysis of Phil Connors’ days in Punxsutawney (37 of which are seen on screen, though the entirety of his purgatory could be anywhere between 30 years (Ramis’ revised estimate) to 10,000 years (amount of time it takes for the soul to evolve to the next level according to Buddhist doctrine), something it’s hard to imagine happening had the film been made today, when philosophical ruminations in voiceover often prove irresistible to filmmakers.

Though the film might feel effortless, it was not. Bill Murray and Ramis would end up not speaking for nearly 20 years after quibbles with the script, which was the subject of several would-be catastrophic changes long before Murray was even in the mix (the role was first offered to Tom Hanks and Michael Keaton).

Initially, screenwriter Danny Rubin wanted to include voiceover narration from Phil, which might have over-explained his mental state that we’re otherwise left to imagine ourselves. Worse, the studio wanted Rubin to make the film more conventional, leading him to acquiesce and submit a new draft in which there was an explanation for Phil being trapped in time – some ghastly plot device involving a scorned girlfriend casting a spell, which Rubin insisted would “take away everything that was innovative and interesting and turn it into an easily-dismissed Hollywood comedy”. There was also talk of, in the third act, giving Phil a sense that he might be able to close the time loop, which presumably would have precipitated an Inception-esque, plot-driven ending.

But Ramis steadied the course and the film stayed playfully simple, having the same kind of shrugging demeanour as the man at the centre of it. The love story shouldn’t work, Murray being so deadpan and non-emotive while Andie McDowell (Rita) dials up the schmaltz, but this ultimately serves to make regular life seem artificial, dreamlike and saccharine, reinforcing Phil’s profound sense of misery and exhaustion amongst it.

The film refuses to date, and different days in Phil’s long life stand out with each repeat viewing, my favourite being the stretch when, having successfully seduced Rita, he tries to do it again on autopilot each day, these scenes bringing to mind the forced conviviality and regurgitated anecdotes of a 58th Tinder date.

A perfectly-balanced movie, Groundhog Day is never taxing, a light, warm film and an “easy watch”, in spite of its propensity to ask big questions like:

How should one live? What should one live for? Hedonism? Knowledge? Charity? Experience? Love? Is it even possible to extricate these from one another?

An endless, perpetual playground, albeit a dreary, small-town Pennsylvania one, is the perfect place to explore these concepts, an intellectual exercise of the greatest significance; for Heidegger, the question of eternal recurrence was the “most burdensome thought”, perhaps the “thought of thoughts”. And yet, Harold Ramis’ Groundhog Day, which turns 25 this month, never struggles under the weight of this philosophical heft, nor does it particularly regard it – it’s almost happenstance.

“I never intended it to be anything more than a good, heartfelt, entertaining story,” Ramis once said, and this is what makes the film so successful. Groundhog Day stays resolutely romcom and refuses to get bogged down in analysis of Phil Connors’ days in Punxsutawney (37 of which are seen on screen, though the entirety of his purgatory could be anywhere between 30 years (Ramis’ revised estimate) to 10,000 years (amount of time it takes for the soul to evolve to the next level according to Buddhist doctrine), something it’s hard to imagine happening had the film been made today, when philosophical ruminations in voiceover often prove irresistible to filmmakers.

Though the film might feel effortless, it was not. Bill Murray and Ramis would end up not speaking for nearly 20 years after quibbles with the script, which was the subject of several would-be catastrophic changes long before Murray was even in the mix (the role was first offered to Tom Hanks and Michael Keaton).

Initially, screenwriter Danny Rubin wanted to include voiceover narration from Phil, which might have over-explained his mental state that we’re otherwise left to imagine ourselves. Worse, the studio wanted Rubin to make the film more conventional, leading him to acquiesce and submit a new draft in which there was an explanation for Phil being trapped in time – some ghastly plot device involving a scorned girlfriend casting a spell, which Rubin insisted would “take away everything that was innovative and interesting and turn it into an easily-dismissed Hollywood comedy”. There was also talk of, in the third act, giving Phil a sense that he might be able to close the time loop, which presumably would have precipitated an Inception-esque, plot-driven ending.

But Ramis steadied the course and the film stayed playfully simple, having the same kind of shrugging demeanour as the man at the centre of it. The love story shouldn’t work, Murray being so deadpan and non-emotive while Andie McDowell (Rita) dials up the schmaltz, but this ultimately serves to make regular life seem artificial, dreamlike and saccharine, reinforcing Phil’s profound sense of misery and exhaustion amongst it.

The film refuses to date, and different days in Phil’s long life stand out with each repeat viewing, my favourite being the stretch when, having successfully seduced Rita, he tries to do it again on autopilot each day, these scenes bringing to mind the forced conviviality and regurgitated anecdotes of a 58th Tinder date.

A perfectly-balanced movie, Groundhog Day is never taxing, a light, warm film and an “easy watch”, in spite of its propensity to ask big questions like:

How should one live? What should one live for? Hedonism? Knowledge? Charity? Experience? Love? Is it even possible to extricate these from one another?

An endless, perpetual playground, albeit a dreary, small-town Pennsylvania one, is the perfect place to explore these concepts, an intellectual exercise of the greatest significance; for Heidegger, the question of eternal recurrence was the “most burdensome thought”, perhaps the “thought of thoughts”. And yet, Harold Ramis’ Groundhog Day, which turns 25 this month, never struggles under the weight of this philosophical heft, nor does it particularly regard it – it’s almost happenstance.

“I never intended it to be anything more than a good, heartfelt, entertaining story,” Ramis once said, and this is what makes the film so successful. Groundhog Day stays resolutely romcom and refuses to get bogged down in analysis of Phil Connors’ days in Punxsutawney (37 of which are seen on screen, though the entirety of his purgatory could be anywhere between 30 years (Ramis’ revised estimate) to 10,000 years (amount of time it takes for the soul to evolve to the next level according to Buddhist doctrine), something it’s hard to imagine happening had the film been made today, when philosophical ruminations in voiceover often prove irresistible to filmmakers.

Though the film might feel effortless, it was not. Bill Murray and Ramis would end up not speaking for nearly 20 years after quibbles with the script, which was the subject of several would-be catastrophic changes long before Murray was even in the mix (the role was first offered to Tom Hanks and Michael Keaton).

Initially, screenwriter Danny Rubin wanted to include voiceover narration from Phil, which might have over-explained his mental state that we’re otherwise left to imagine ourselves. Worse, the studio wanted Rubin to make the film more conventional, leading him to acquiesce and submit a new draft in which there was an explanation for Phil being trapped in time – some ghastly plot device involving a scorned girlfriend casting a spell, which Rubin insisted would “take away everything that was innovative and interesting and turn it into an easily-dismissed Hollywood comedy”. There was also talk of, in the third act, giving Phil a sense that he might be able to close the time loop, which presumably would have precipitated an Inception-esque, plot-driven ending.

But Ramis steadied the course and the film stayed playfully simple, having the same kind of shrugging demeanour as the man at the centre of it. The love story shouldn’t work, Murray being so deadpan and non-emotive while Andie McDowell (Rita) dials up the schmaltz, but this ultimately serves to make regular life seem artificial, dreamlike and saccharine, reinforcing Phil’s profound sense of misery and exhaustion amongst it.

The film refuses to date, and different days in Phil’s long life stand out with each repeat viewing, my favourite being the stretch when, having successfully seduced Rita, he tries to do it again on autopilot each day, these scenes bringing to mind the forced conviviality and regurgitated anecdotes of a 58th Tinder date.

A perfectly-balanced movie, Groundhog Day is never taxing, a light, warm film and an “easy watch”, in spite of its propensity to ask big questions like:

How should one live? What should one live for? Hedonism? Knowledge? Charity? Experience? Love? Is it even possible to extricate these from one another?

An endless, perpetual playground, albeit a dreary, small-town Pennsylvania one, is the perfect place to explore these concepts, an intellectual exercise of the greatest significance; for Heidegger, the question of eternal recurrence was the “most burdensome thought”, perhaps the “thought of thoughts”. And yet, Harold Ramis’ Groundhog Day, which turns 25 this month, never struggles under the weight of this philosophical heft, nor does it particularly regard it – it’s almost happenstance.

“I never intended it to be anything more than a good, heartfelt, entertaining story,” Ramis once said, and this is what makes the film so successful. Groundhog Day stays resolutely romcom and refuses to get bogged down in analysis of Phil Connors’ days in Punxsutawney (37 of which are seen on screen, though the entirety of his purgatory could be anywhere between 30 years (Ramis’ revised estimate) to 10,000 years (amount of time it takes for the soul to evolve to the next level according to Buddhist doctrine), something it’s hard to imagine happening had the film been made today, when philosophical ruminations in voiceover often prove irresistible to filmmakers.

Though the film might feel effortless, it was not. Bill Murray and Ramis would end up not speaking for nearly 20 years after quibbles with the script, which was the subject of several would-be catastrophic changes long before Murray was even in the mix (the role was first offered to Tom Hanks and Michael Keaton).

Initially, screenwriter Danny Rubin wanted to include voiceover narration from Phil, which might have over-explained his mental state that we’re otherwise left to imagine ourselves. Worse, the studio wanted Rubin to make the film more conventional, leading him to acquiesce and submit a new draft in which there was an explanation for Phil being trapped in time – some ghastly plot device involving a scorned girlfriend casting a spell, which Rubin insisted would “take away everything that was innovative and interesting and turn it into an easily-dismissed Hollywood comedy”. There was also talk of, in the third act, giving Phil a sense that he might be able to close the time loop, which presumably would have precipitated an Inception-esque, plot-driven ending.

But Ramis steadied the course and the film stayed playfully simple, having the same kind of shrugging demeanour as the man at the centre of it. The love story shouldn’t work, Murray being so deadpan and non-emotive while Andie McDowell (Rita) dials up the schmaltz, but this ultimately serves to make regular life seem artificial, dreamlike and saccharine, reinforcing Phil’s profound sense of misery and exhaustion amongst it.

The film refuses to date, and different days in Phil’s long life stand out with each repeat viewing, my favourite being the stretch when, having successfully seduced Rita, he tries to do it again on autopilot each day, these scenes bringing to mind the forced conviviality and regurgitated anecdotes of a 58th Tinder date.

A perfectly-balanced movie, Groundhog Day is never taxing, a light, warm film and an “easy watch”, in spite of its propensity to ask big questions like:

How should one live? What should one live for? Hedonism? Knowledge? Charity? Experience? Love? Is it even possible to extricate these from one another?

An endless, perpetual playground, albeit a dreary, small-town Pennsylvania one, is the perfect place to explore these concepts, an intellectual exercise of the greatest significance; for Heidegger, the question of eternal recurrence was the “most burdensome thought”, perhaps the “thought of thoughts”. And yet, Harold Ramis’ Groundhog Day, which turns 25 this month, never struggles under the weight of this philosophical heft, nor does it particularly regard it – it’s almost happenstance.

“I never intended it to be anything more than a good, heartfelt, entertaining story,” Ramis once said, and this is what makes the film so successful. Groundhog Day stays resolutely romcom and refuses to get bogged down in analysis of Phil Connors’ days in Punxsutawney (37 of which are seen on screen, though the entirety of his purgatory could be anywhere between 30 years (Ramis’ revised estimate) to 10,000 years (amount of time it takes for the soul to evolve to the next level according to Buddhist doctrine), something it’s hard to imagine happening had the film been made today, when philosophical ruminations in voiceover often prove irresistible to filmmakers.

Though the film might feel effortless, it was not. Bill Murray and Ramis would end up not speaking for nearly 20 years after quibbles with the script, which was the subject of several would-be catastrophic changes long before Murray was even in the mix (the role was first offered to Tom Hanks and Michael Keaton).

Initially, screenwriter Danny Rubin wanted to include voiceover narration from Phil, which might have over-explained his mental state that we’re otherwise left to imagine ourselves. Worse, the studio wanted Rubin to make the film more conventional, leading him to acquiesce and submit a new draft in which there was an explanation for Phil being trapped in time – some ghastly plot device involving a scorned girlfriend casting a spell, which Rubin insisted would “take away everything that was innovative and interesting and turn it into an easily-dismissed Hollywood comedy”. There was also talk of, in the third act, giving Phil a sense that he might be able to close the time loop, which presumably would have precipitated an Inception-esque, plot-driven ending.

But Ramis steadied the course and the film stayed playfully simple, having the same kind of shrugging demeanour as the man at the centre of it. The love story shouldn’t work, Murray being so deadpan and non-emotive while Andie McDowell (Rita) dials up the schmaltz, but this ultimately serves to make regular life seem artificial, dreamlike and saccharine, reinforcing Phil’s profound sense of misery and exhaustion amongst it.

The film refuses to date, and different days in Phil’s long life stand out with each repeat viewing, my favourite being the stretch when, having successfully seduced Rita, he tries to do it again on autopilot each day, these scenes bringing to mind the forced conviviality and regurgitated anecdotes of a 58th Tinder date.

A perfectly-balanced movie, Groundhog Day is never taxing, a light, warm film and an “easy watch”, in spite of its propensity to ask big questions like:

How should one live? What should one live for? Hedonism? Knowledge? Charity? Experience? Love? Is it even possible to extricate these from one another?

An endless, perpetual playground, albeit a dreary, small-town Pennsylvania one, is the perfect place to explore these concepts, an intellectual exercise of the greatest significance; for Heidegger, the question of eternal recurrence was the “most burdensome thought”, perhaps the “thought of thoughts”. And yet, Harold Ramis’ Groundhog Day, which turns 25 this month, never struggles under the weight of this philosophical heft, nor does it particularly regard it – it’s almost happenstance.

“I never intended it to be anything more than a good, heartfelt, entertaining story,” Ramis once said, and this is what makes the film so successful. Groundhog Day stays resolutely romcom and refuses to get bogged down in analysis of Phil Connors’ days in Punxsutawney (37 of which are seen on screen, though the entirety of his purgatory could be anywhere between 30 years (Ramis’ revised estimate) to 10,000 years (amount of time it takes for the soul to evolve to the next level according to Buddhist doctrine), something it’s hard to imagine happening had the film been made today, when philosophical ruminations in voiceover often prove irresistible to filmmakers.

Though the film might feel effortless, it was not. Bill Murray and Ramis would end up not speaking for nearly 20 years after quibbles with the script, which was the subject of several would-be catastrophic changes long before Murray was even in the mix (the role was first offered to Tom Hanks and Michael Keaton).

Initially, screenwriter Danny Rubin wanted to include voiceover narration from Phil, which might have over-explained his mental state that we’re otherwise left to imagine ourselves. Worse, the studio wanted Rubin to make the film more conventional, leading him to acquiesce and submit a new draft in which there was an explanation for Phil being trapped in time – some ghastly plot device involving a scorned girlfriend casting a spell, which Rubin insisted would “take away everything that was innovative and interesting and turn it into an easily-dismissed Hollywood comedy”. There was also talk of, in the third act, giving Phil a sense that he might be able to close the time loop, which presumably would have precipitated an Inception-esque, plot-driven ending.

But Ramis steadied the course and the film stayed playfully simple, having the same kind of shrugging demeanour as the man at the centre of it. The love story shouldn’t work, Murray being so deadpan and non-emotive while Andie McDowell (Rita) dials up the schmaltz, but this ultimately serves to make regular life seem artificial, dreamlike and saccharine, reinforcing Phil’s profound sense of misery and exhaustion amongst it.

The film refuses to date, and different days in Phil’s long life stand out with each repeat viewing, my favourite being the stretch when, having successfully seduced Rita, he tries to do it again on autopilot each day, these scenes bringing to mind the forced conviviality and regurgitated anecdotes of a 58th Tinder date.

A perfectly-balanced movie, Groundhog Day is never taxing, a light, warm film and an “easy watch”, in spite of its propensity to ask big questions like:

How should one live? What should one live for? Hedonism? Knowledge? Charity? Experience? Love? Is it even possible to extricate these from one another?

An endless, perpetual playground, albeit a dreary, small-town Pennsylvania one, is the perfect place to explore these concepts, an intellectual exercise of the greatest significance; for Heidegger, the question of eternal recurrence was the “most burdensome thought”, perhaps the “thought of thoughts”. And yet, Harold Ramis’ Groundhog Day, which turns 25 this month, never struggles under the weight of this philosophical heft, nor does it particularly regard it – it’s almost happenstance.

“I never intended it to be anything more than a good, heartfelt, entertaining story,” Ramis once said, and this is what makes the film so successful. Groundhog Day stays resolutely romcom and refuses to get bogged down in analysis of Phil Connors’ days in Punxsutawney (37 of which are seen on screen, though the entirety of his purgatory could be anywhere between 30 years (Ramis’ revised estimate) to 10,000 years (amount of time it takes for the soul to evolve to the next level according to Buddhist doctrine), something it’s hard to imagine happening had the film been made today, when philosophical ruminations in voiceover often prove irresistible to filmmakers.

Though the film might feel effortless, it was not. Bill Murray and Ramis would end up not speaking for nearly 20 years after quibbles with the script, which was the subject of several would-be catastrophic changes long before Murray was even in the mix (the role was first offered to Tom Hanks and Michael Keaton).

Initially, screenwriter Danny Rubin wanted to include voiceover narration from Phil, which might have over-explained his mental state that we’re otherwise left to imagine ourselves. Worse, the studio wanted Rubin to make the film more conventional, leading him to acquiesce and submit a new draft in which there was an explanation for Phil being trapped in time – some ghastly plot device involving a scorned girlfriend casting a spell, which Rubin insisted would “take away everything that was innovative and interesting and turn it into an easily-dismissed Hollywood comedy”. There was also talk of, in the third act, giving Phil a sense that he might be able to close the time loop, which presumably would have precipitated an Inception-esque, plot-driven ending.

But Ramis steadied the course and the film stayed playfully simple, having the same kind of shrugging demeanour as the man at the centre of it. The love story shouldn’t work, Murray being so deadpan and non-emotive while Andie McDowell (Rita) dials up the schmaltz, but this ultimately serves to make regular life seem artificial, dreamlike and saccharine, reinforcing Phil’s profound sense of misery and exhaustion amongst it.

The film refuses to date, and different days in Phil’s long life stand out with each repeat viewing, my favourite being the stretch when, having successfully seduced Rita, he tries to do it again on autopilot each day, these scenes bringing to mind the forced conviviality and regurgitated anecdotes of a 58th Tinder date.

A perfectly-balanced movie, Groundhog Day is never taxing, a light, warm film and an “easy watch”, in spite of its propensity to ask big questions like:

How should one live? What should one live for? Hedonism? Knowledge? Charity? Experience? Love? Is it even possible to extricate these from one another?

An endless, perpetual playground, albeit a dreary, small-town Pennsylvania one, is the perfect place to explore these concepts, an intellectual exercise of the greatest significance; for Heidegger, the question of eternal recurrence was the “most burdensome thought”, perhaps the “thought of thoughts”. And yet, Harold Ramis’ Groundhog Day, which turns 25 this month, never struggles under the weight of this philosophical heft, nor does it particularly regard it – it’s almost happenstance.

“I never intended it to be anything more than a good, heartfelt, entertaining story,” Ramis once said, and this is what makes the film so successful. Groundhog Day stays resolutely romcom and refuses to get bogged down in analysis of Phil Connors’ days in Punxsutawney (37 of which are seen on screen, though the entirety of his purgatory could be anywhere between 30 years (Ramis’ revised estimate) to 10,000 years (amount of time it takes for the soul to evolve to the next level according to Buddhist doctrine), something it’s hard to imagine happening had the film been made today, when philosophical ruminations in voiceover often prove irresistible to filmmakers.

Though the film might feel effortless, it was not. Bill Murray and Ramis would end up not speaking for nearly 20 years after quibbles with the script, which was the subject of several would-be catastrophic changes long before Murray was even in the mix (the role was first offered to Tom Hanks and Michael Keaton).

Initially, screenwriter Danny Rubin wanted to include voiceover narration from Phil, which might have over-explained his mental state that we’re otherwise left to imagine ourselves. Worse, the studio wanted Rubin to make the film more conventional, leading him to acquiesce and submit a new draft in which there was an explanation for Phil being trapped in time – some ghastly plot device involving a scorned girlfriend casting a spell, which Rubin insisted would “take away everything that was innovative and interesting and turn it into an easily-dismissed Hollywood comedy”. There was also talk of, in the third act, giving Phil a sense that he might be able to close the time loop, which presumably would have precipitated an Inception-esque, plot-driven ending.

But Ramis steadied the course and the film stayed playfully simple, having the same kind of shrugging demeanour as the man at the centre of it. The love story shouldn’t work, Murray being so deadpan and non-emotive while Andie McDowell (Rita) dials up the schmaltz, but this ultimately serves to make regular life seem artificial, dreamlike and saccharine, reinforcing Phil’s profound sense of misery and exhaustion amongst it.

The film refuses to date, and different days in Phil’s long life stand out with each repeat viewing, my favourite being the stretch when, having successfully seduced Rita, he tries to do it again on autopilot each day, these scenes bringing to mind the forced conviviality and regurgitated anecdotes of a 58th Tinder date.

A perfectly-balanced movie, Groundhog Day is never taxing, a light, warm film and an “easy watch”, in spite of its propensity to ask big questions like:

How should one live? What should one live for? Hedonism? Knowledge? Charity? Experience? Love? Is it even possible to extricate these from one another?

An endless, perpetual playground, albeit a dreary, small-town Pennsylvania one, is the perfect place to explore these concepts, an intellectual exercise of the greatest significance; for Heidegger, the question of eternal recurrence was the “most burdensome thought”, perhaps the “thought of thoughts”. And yet, Harold Ramis’ Groundhog Day, which turns 25 this month, never struggles under the weight of this philosophical heft, nor does it particularly regard it – it’s almost happenstance.

“I never intended it to be anything more than a good, heartfelt, entertaining story,” Ramis once said, and this is what makes the film so successful. Groundhog Day stays resolutely romcom and refuses to get bogged down in analysis of Phil Connors’ days in Punxsutawney (37 of which are seen on screen, though the entirety of his purgatory could be anywhere between 30 years (Ramis’ revised estimate) to 10,000 years (amount of time it takes for the soul to evolve to the next level according to Buddhist doctrine), something it’s hard to imagine happening had the film been made today, when philosophical ruminations in voiceover often prove irresistible to filmmakers.

Though the film might feel effortless, it was not. Bill Murray and Ramis would end up not speaking for nearly 20 years after quibbles with the script, which was the subject of several would-be catastrophic changes long before Murray was even in the mix (the role was first offered to Tom Hanks and Michael Keaton).

Initially, screenwriter Danny Rubin wanted to include voiceover narration from Phil, which might have over-explained his mental state that we’re otherwise left to imagine ourselves. Worse, the studio wanted Rubin to make the film more conventional, leading him to acquiesce and submit a new draft in which there was an explanation for Phil being trapped in time – some ghastly plot device involving a scorned girlfriend casting a spell, which Rubin insisted would “take away everything that was innovative and interesting and turn it into an easily-dismissed Hollywood comedy”. There was also talk of, in the third act, giving Phil a sense that he might be able to close the time loop, which presumably would have precipitated an Inception-esque, plot-driven ending.

But Ramis steadied the course and the film stayed playfully simple, having the same kind of shrugging demeanour as the man at the centre of it. The love story shouldn’t work, Murray being so deadpan and non-emotive while Andie McDowell (Rita) dials up the schmaltz, but this ultimately serves to make regular life seem artificial, dreamlike and saccharine, reinforcing Phil’s profound sense of misery and exhaustion amongst it.

The film refuses to date, and different days in Phil’s long life stand out with each repeat viewing, my favourite being the stretch when, having successfully seduced Rita, he tries to do it again on autopilot each day, these scenes bringing to mind the forced conviviality and regurgitated anecdotes of a 58th Tinder date.

A perfectly-balanced movie, Groundhog Day is never taxing, a light, warm film and an “easy watch”, in spite of its propensity to ask big questions like:

How should one live? What should one live for? Hedonism? Knowledge? Charity? Experience? Love? Is it even possible to extricate these from one another?

An endless, perpetual playground, albeit a dreary, small-town Pennsylvania one, is the perfect place to explore these concepts, an intellectual exercise of the greatest significance; for Heidegger, the question of eternal recurrence was the “most burdensome thought”, perhaps the “thought of thoughts”. And yet, Harold Ramis’ Groundhog Day, which turns 25 this month, never struggles under the weight of this philosophical heft, nor does it particularly regard it – it’s almost happenstance.

“I never intended it to be anything more than a good, heartfelt, entertaining story,” Ramis once said, and this is what makes the film so successful. Groundhog Day stays resolutely romcom and refuses to get bogged down in analysis of Phil Connors’ days in Punxsutawney (37 of which are seen on screen, though the entirety of his purgatory could be anywhere between 30 years (Ramis’ revised estimate) to 10,000 years (amount of time it takes for the soul to evolve to the next level according to Buddhist doctrine), something it’s hard to imagine happening had the film been made today, when philosophical ruminations in voiceover often prove irresistible to filmmakers.

Though the film might feel effortless, it was not. Bill Murray and Ramis would end up not speaking for nearly 20 years after quibbles with the script, which was the subject of several would-be catastrophic changes long before Murray was even in the mix (the role was first offered to Tom Hanks and Michael Keaton).

Initially, screenwriter Danny Rubin wanted to include voiceover narration from Phil, which might have over-explained his mental state that we’re otherwise left to imagine ourselves. Worse, the studio wanted Rubin to make the film more conventional, leading him to acquiesce and submit a new draft in which there was an explanation for Phil being trapped in time – some ghastly plot device involving a scorned girlfriend casting a spell, which Rubin insisted would “take away everything that was innovative and interesting and turn it into an easily-dismissed Hollywood comedy”. There was also talk of, in the third act, giving Phil a sense that he might be able to close the time loop, which presumably would have precipitated an Inception-esque, plot-driven ending.

But Ramis steadied the course and the film stayed playfully simple, having the same kind of shrugging demeanour as the man at the centre of it. The love story shouldn’t work, Murray being so deadpan and non-emotive while Andie McDowell (Rita) dials up the schmaltz, but this ultimately serves to make regular life seem artificial, dreamlike and saccharine, reinforcing Phil’s profound sense of misery and exhaustion amongst it.

The film refuses to date, and different days in Phil’s long life stand out with each repeat viewing, my favourite being the stretch when, having successfully seduced Rita, he tries to do it again on autopilot each day, these scenes bringing to mind the forced conviviality and regurgitated anecdotes of a 58th Tinder date.

A perfectly-balanced movie, Groundhog Day is never taxing, a light, warm film and an “easy watch”, in spite of its propensity to ask big questions like:

How should one live? What should one live for? Hedonism? Knowledge? Charity? Experience? Love? Is it even possible to extricate these from one another?

An endless, perpetual playground, albeit a dreary, small-town Pennsylvania one, is the perfect place to explore these concepts, an intellectual exercise of the greatest significance; for Heidegger, the question of eternal recurrence was the “most burdensome thought”, perhaps the “thought of thoughts”. And yet, Harold Ramis’ Groundhog Day, which turns 25 this month, never struggles under the weight of this philosophical heft, nor does it particularly regard it – it’s almost happenstance.

“I never intended it to be anything more than a good, heartfelt, entertaining story,” Ramis once said, and this is what makes the film so successful. Groundhog Day stays resolutely romcom and refuses to get bogged down in analysis of Phil Connors’ days in Punxsutawney (37 of which are seen on screen, though the entirety of his purgatory could be anywhere between 30 years (Ramis’ revised estimate) to 10,000 years (amount of time it takes for the soul to evolve to the next level according to Buddhist doctrine), something it’s hard to imagine happening had the film been made today, when philosophical ruminations in voiceover often prove irresistible to filmmakers.

Though the film might feel effortless, it was not. Bill Murray and Ramis would end up not speaking for nearly 20 years after quibbles with the script, which was the subject of several would-be catastrophic changes long before Murray was even in the mix (the role was first offered to Tom Hanks and Michael Keaton).

Initially, screenwriter Danny Rubin wanted to include voiceover narration from Phil, which might have over-explained his mental state that we’re otherwise left to imagine ourselves. Worse, the studio wanted Rubin to make the film more conventional, leading him to acquiesce and submit a new draft in which there was an explanation for Phil being trapped in time – some ghastly plot device involving a scorned girlfriend casting a spell, which Rubin insisted would “take away everything that was innovative and interesting and turn it into an easily-dismissed Hollywood comedy”. There was also talk of, in the third act, giving Phil a sense that he might be able to close the time loop, which presumably would have precipitated an Inception-esque, plot-driven ending.

But Ramis steadied the course and the film stayed playfully simple, having the same kind of shrugging demeanour as the man at the centre of it. The love story shouldn’t work, Murray being so deadpan and non-emotive while Andie McDowell (Rita) dials up the schmaltz, but this ultimately serves to make regular life seem artificial, dreamlike and saccharine, reinforcing Phil’s profound sense of misery and exhaustion amongst it.

The film refuses to date, and different days in Phil’s long life stand out with each repeat viewing, my favourite being the stretch when, having successfully seduced Rita, he tries to do it again on autopilot each day, these scenes bringing to mind the forced conviviality and regurgitated anecdotes of a 58th Tinder date.

A perfectly-balanced movie, Groundhog Day is never taxing, a light, warm film and an “easy watch”, in spite of its propensity to ask big questions like:

How should one live? What should one live for? Hedonism? Knowledge? Charity? Experience? Love? Is it even possible to extricate these from one another?

An endless, perpetual playground, albeit a dreary, small-town Pennsylvania one, is the perfect place to explore these concepts, an intellectual exercise of the greatest significance; for Heidegger, the question of eternal recurrence was the “most burdensome thought”, perhaps the “thought of thoughts”. And yet, Harold Ramis’ Groundhog Day, which turns 25 this month, never struggles under the weight of this philosophical heft, nor does it particularly regard it – it’s almost happenstance.

“I never intended it to be anything more than a good, heartfelt, entertaining story,” Ramis once said, and this is what makes the film so successful. Groundhog Day stays resolutely romcom and refuses to get bogged down in analysis of Phil Connors’ days in Punxsutawney (37 of which are seen on screen, though the entirety of his purgatory could be anywhere between 30 years (Ramis’ revised estimate) to 10,000 years (amount of time it takes for the soul to evolve to the next level according to Buddhist doctrine), something it’s hard to imagine happening had the film been made today, when philosophical ruminations in voiceover often prove irresistible to filmmakers.

Though the film might feel effortless, it was not. Bill Murray and Ramis would end up not speaking for nearly 20 years after quibbles with the script, which was the subject of several would-be catastrophic changes long before Murray was even in the mix (the role was first offered to Tom Hanks and Michael Keaton).

Initially, screenwriter Danny Rubin wanted to include voiceover narration from Phil, which might have over-explained his mental state that we’re otherwise left to imagine ourselves. Worse, the studio wanted Rubin to make the film more conventional, leading him to acquiesce and submit a new draft in which there was an explanation for Phil being trapped in time – some ghastly plot device involving a scorned girlfriend casting a spell, which Rubin insisted would “take away everything that was innovative and interesting and turn it into an easily-dismissed Hollywood comedy”. There was also talk of, in the third act, giving Phil a sense that he might be able to close the time loop, which presumably would have precipitated an Inception-esque, plot-driven ending.

But Ramis steadied the course and the film stayed playfully simple, having the same kind of shrugging demeanour as the man at the centre of it. The love story shouldn’t work, Murray being so deadpan and non-emotive while Andie McDowell (Rita) dials up the schmaltz, but this ultimately serves to make regular life seem artificial, dreamlike and saccharine, reinforcing Phil’s profound sense of misery and exhaustion amongst it.

The film refuses to date, and different days in Phil’s long life stand out with each repeat viewing, my favourite being the stretch when, having successfully seduced Rita, he tries to do it again on autopilot each day, these scenes bringing to mind the forced conviviality and regurgitated anecdotes of a 58th Tinder date.

A perfectly-balanced movie, Groundhog Day is never taxing, a light, warm film and an “easy watch”, in spite of its propensity to ask big questions like:

How should one live? What should one live for? Hedonism? Knowledge? Charity? Experience? Love? Is it even possible to extricate these from one another?

An endless, perpetual playground, albeit a dreary, small-town Pennsylvania one, is the perfect place to explore these concepts, an intellectual exercise of the greatest significance; for Heidegger, the question of eternal recurrence was the “most burdensome thought”, perhaps the “thought of thoughts”. And yet, Harold Ramis’ Groundhog Day, which turns 25 this month, never struggles under the weight of this philosophical heft, nor does it particularly regard it – it’s almost happenstance.

“I never intended it to be anything more than a good, heartfelt, entertaining story,” Ramis once said, and this is what makes the film so successful. Groundhog Day stays resolutely romcom and refuses to get bogged down in analysis of Phil Connors’ days in Punxsutawney (37 of which are seen on screen, though the entirety of his purgatory could be anywhere between 30 years (Ramis’ revised estimate) to 10,000 years (amount of time it takes for the soul to evolve to the next level according to Buddhist doctrine), something it’s hard to imagine happening had the film been made today, when philosophical ruminations in voiceover often prove irresistible to filmmakers.

Though the film might feel effortless, it was not. Bill Murray and Ramis would end up not speaking for nearly 20 years after quibbles with the script, which was the subject of several would-be catastrophic changes long before Murray was even in the mix (the role was first offered to Tom Hanks and Michael Keaton).