Gérard Depardieu’s brutish onscreen brilliance can’t save a legacy in freefall

He’s faced allegations of sexual abuse from more than a dozen women and yet only last month was called ‘a great actor who makes France proud’ by President Macron. Geoffrey Macnab unpicks a cinematic scandal that goes back decades – and finds younger fans of film ready to shunt the star off screen and into permanent obscurity

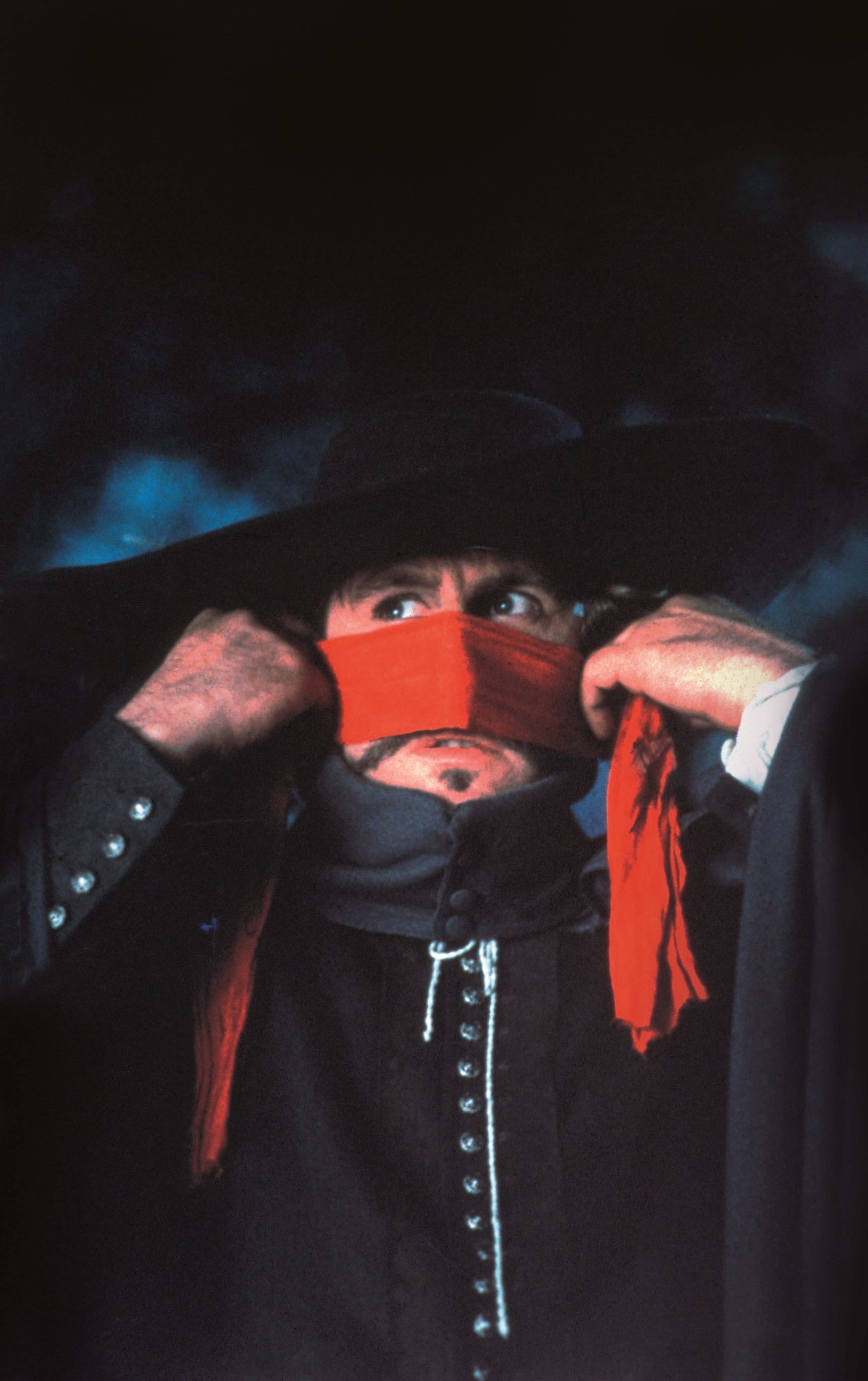

Poets and thugs: Gérard Depardieu always excelled at playing both. Projecting a yearning vulnerability, the hulking French actor’s best performances invariably walked a line between brutishness and delicacy. In the words of critic David Thomson, he has “the air of a rugby player... crossed with a great violinist”.

Today, it seems crass even to discuss Depardieu’s acting, given that he is facing multiple allegations of rape and sexual assault. The 75-year-old has denied emphatically that he is a rapist or a predator, telling Le Figaro: “I have never, ever abused a woman. Hurting a woman would be like kicking my own mother in the stomach.”

This week, Parisian prosecutors dismissed a complaint by actor Hélène Darras, who claimed that he had groped and propositioned her on the set of the 2007 film Disco. The case was abandoned after exceeding the statute of limitations; a dozen other women also lodged allegations against the actor last year.

The scandal has been raked over exhaustively in the French and international media. Audiences who were so moved by Depardieu’s performance as the ungainly, big-nosed soldier with the romantic soul in Cyrano de Bergerac, or by his role as the hunchback city dweller trying to build a life in the country in Jean de Florette, feel horribly betrayed. Questions are being asked about whether his films should remain in circulation – and whether people will still want to watch them.

Actors such as Kevin Spacey and Armie Hammer have seen mainstream Hollywood roles dry up in the wake of abuse allegations; token attempts are now being made to take Depardieu out of the public eye, too. Last month, his movies were yanked off Swiss public television. He had his waxwork removed from one French museum. A senior French TV exec insisted his work must not be “celebrated”. A Belgian town revoked his honorary citizenship. He was “stripped” of the National Order of Quebec.

Most of his movies, though, are still freely available in France and abroad. He is so intricately woven into the fabric of French cultural life over the last 50 years that it is almost impossible to cut him out. Internationally, he is also a huge figure – a Golden Globe winner and an Oscar nominee. Look at his filmography and you’ll find around 250 credits, including features and TV dramas. Erasing him and his work would leave a sizeable crater in French film culture. It would mean disregarding the efforts of his celebrated collaborators, and would prompt frenzied discussions about censorship, witch-hunts and freedom of speech.

Throughout his career, Depardieu has worked with revolutionary filmmakers such as François Truffaut, Agnès Varda, Marguerite Duras, Jean-Luc Godard and Claude Chabrol – and their collaborations are bound to be caught up in the row. As Le Figaro recently wrote, the Depardieu affair threatens to pull apart the “great family” of French cinema. The danger is that the younger generation will want nothing to do with its parents’ era – and that many great movies may be shunted into obscurity as a result.

More problematic, perhaps, is Depardieu’s continued involvement in new acting projects. He can be seen, for instance, as bulky Inspector Maigret in a recent adaptation of the Georges Simenon detective novels that recently launched on Prime Video. Netflix, meanwhile, is still streaming Marseille, its first French-language original production, in which he stars. Approached this week by The Independent about its stance on Depardieu, Netflix did not comment.

Some will argue they have no need to distance themselves from him. After all, French president Emmanuel Macron last month described him as “a great actor who makes France proud”, and said there was no question of taking away his Legion of Honour. Some of the actor’s contemporaries, including Charlotte Rampling and Carole Bouquet, signed a letter in his support. His champions are defending him on artistic grounds – but are showing an obvious tone-deafness in doing so. What they’re conspicuously failing even to acknowledge is the suffering and humiliation of his alleged victims.

As the controversy over the actor rumbles on, battle lines are being drawn across generational and gender divides. “The pro-Depardieu camp are seen by most everyone else in France as these kind of old, past-it boomers who love their sexual prerogative to run around abusing everyone they want,” US journalist Alexandra Marshall claimed in a recent edition of Air Mail’s Morning Meeting podcast. On the other side of the debate, she said, were “the younger more responsible people of today who are greatly affected by #MeToo and want people to remember that art is not an excuse to abuse women”.

Depardieu has a knack of wrong-footing his critics. A decade ago, I attended a late-night press conference on a Cannes beach for Abel Ferrara’s 2014 feature Welcome to New York. This was the notorious film in which he starred as a powerful politician accused of raping a maid in a New York hotel. At the time, there was another media storm around him – because he had been cosying up to Russian president Vladimir Putin and had recently accepted Russian citizenship. Memories were also still fresh of him urinating publicly in a plane in 2011.

The journalists in attendance didn’t know what to expect, but Depardieu soon had them eating out of his hand. He came across as gracious, charming, articulate, and very deferential to his co-star, Jacqueline Bisset, who played the wronged wife. It was impossible to reconcile the man in front of us with the ogre then being portrayed in the media. This was the actor in violinist mode.

But Depardieu has always been a contradictory figure, trailing chaos in his wake. “My biggest battle is my excessiveness,” he acknowledged early in his career. Even on screen, he is drawn to extreme roles, such as the 1976 film The Last Woman, in which he is shown sawing off his own penis. Off screen, he has continually behaved as if normal social constraints simply don’t apply to him.

There is a reason Depardieu doesn’t have a Hollywood career. During the early 1990s, a huge controversy exploded over what the US press called his “very sordid past” after he allegedly admitted to Time magazine that he had “participated” in rapes as “part of my childhood”. His 1991 biographer Marianne Gray reported that two of his most famous films, Green Card and Cyrano, were boycotted even then. Depardieu subsequently accused Time of mistranslating the quote, insisting that he had admitted only to having witnessed rapes.

This is why it’s so important that he is held to account now. He may be one of French cinema’s greatest and most versatile talents, but that doesn’t give him a licence to abuse. The myth that his excesses somehow feed his brilliance can’t be allowed to stand.