Scream queens: Remembering the short-lived queer villains of horror

A trio of 1980s thrillers made LGBT+ killers their focus, and were problematic in their day – but 40 years later, these films are being reappraised. Their outwardly queer villainy hasn’t been repeated since, says Adam White

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was the late 1970s, and the burgeoning gay rights movement had become too important for Hollywood to ignore. A decade earlier, the Stonewall riots had led to a wave of political progress – sexual orientation was becoming a new factor in anti-discrimination laws across the United States; pride marches and grassroots gay and lesbian organisations were born; and collective demand for equality reached fever pitch. In tandem with the real world, cinema got queered, too. In 1980, three major movies were released that featured openly queer leads. They also happened to be murderers and psychopaths.

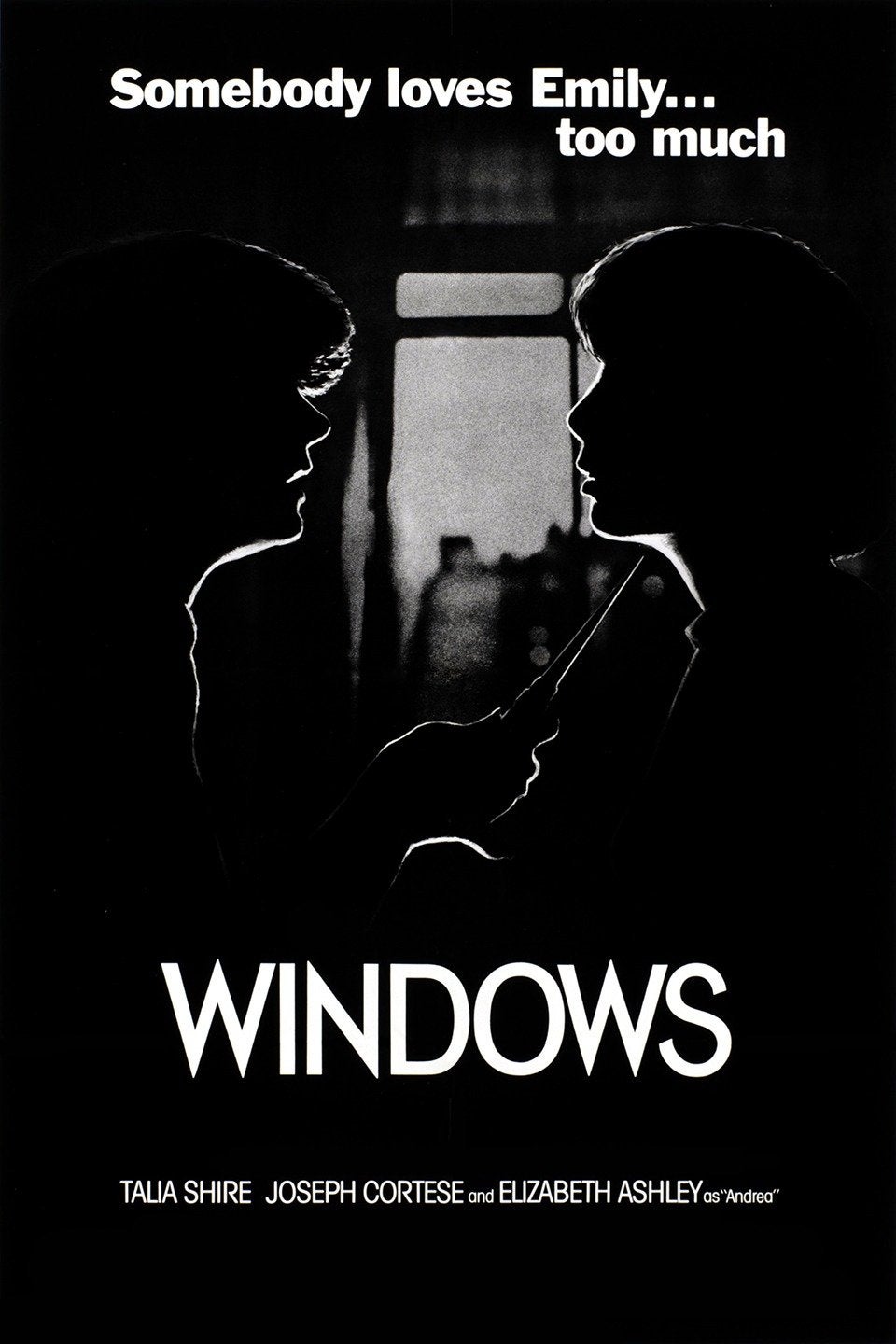

In William Friedkin’s “erotic thriller” Cruising, Al Pacino is a rookie cop who ventures into New York’s leather scene to catch a gay killer targeting other gay men. In Brian De Palma’s Dressed to Kill, a transgender psychiatrist embarks on a series of sordid murders, with two plucky straights tasked with unravelling the mystery. And in Gordon Willis’s Windows, a vulnerable young woman is stalked by her lesbian best friend, who secretly watches her through a telescope and pays a man to sexually assault her.

All three are sleazy metropolitan nightmares, with naive heterosexuals terrorised by the queer unknown. They were also picketed during their respective productions, before being engulfed by controversy upon release. At a time when positive representation was most needed, these movies were awash in negative portrayals of queerness. But in the intervening decades since their release 40 years ago, it’s possible to view them in another light. There’s a strange power to these films, primarily because depictions of deliciously evil and unambiguously queer villainy are so rare. Two have been reframed as cult classics: Cruising and Dressed to Kill are today typically regarded as transgressive queer thrillers awash in deliberate luridness, their modern appreciation speaking to the ebbs and flows of queer acceptance. They also showcase how stagnant queer representation in the mainstream has tended to be in the decades since.

In 1979, months after the assassination of Harvey Milk, California’s first openly gay elected official, this trio of movies were seen as a matter of life and death. “Cruising is not a film about how we live, it is a film about why we should be killed,” wrote Arthur Bell in New York’s Village Voice newspaper. He would urge gay New Yorkers and allies to disrupt production of the film and play loud music during the shooting of street scenes. A San Francisco-based activist group known as Women Against Violence in Pornography and the Media similarly called for a boycott of Dressed to Kill and Windows, with both films accused of glorifying violence against women and demonising the lesbian and transgender communities.

Considering all three films were written and directed by straight men, and the idea of queer equality was at the time so frightening to conservative America, few of their narratives were particularly surprising. After all, the country was built on a rigid understanding of sex and gender, and anyone existing outside of a repressed value system tended to be feared. If the cinema of the 1970s, from Dirty Harry to Death Wish, had instructed audiences to fear the black, working-class male, the 1980s seemed to pick the LGBT+ community as the new boogeyman.

This demonisation, says Dr Jon Mitchell, senior lecturer in American Studies at the University of East Anglia, was a continuation of the instincts hardwired to the American psyche. “The US has a long history of constituting itself against otherness,” he explains. “Whether it’s the Puritans with the devil and witches, the US against the Soviets, or militia groups against the new world order. The ‘sexual psychopath’ was just one in a long cast of ‘villains’.”

Elements of the outrage channel the times. At a moment in which the most vocal opponents of gay rights would talk of the leather-clad deviance of queer sex, Cruising’s exclusive focus on gay kink – which would serve as an introduction to queer sex for many viewers at the time – wasn’t a particularly everyday depiction. The terrible screenplays for both Windows and Dressed to Kill also meant their respective villains were confused creations. In Windows, its sole lesbian character seems to believe a straight woman’s sexuality would change if she is assaulted by a man. And Dressed to Kill’s ignorance reduces transgender identity to a kind of split-personality disorder, the film’s villain being at the mercy of male and female psychological “personas” who are fighting for control.

“They traffic in problematic tropes,” says Mitchell of the trio of films. “There’s the ‘dead gay’, ‘the sexual psychopath’, ‘the pervert’, ‘the paedophile’. This isn’t to say that the film-makers were doing it deliberately but they’re there to appease the cultural sensitivities of the conservative zeitgeist.”

Of the three films that appalled queer audiences in 1980, only Cruising could be considered a genuine work of art. While there’s a detached, almost anthropological quality to Friedkin’s dramatisation of gay sexuality, there’s also something richly empathetic about his approach, too. The leather bar at the centre of the film is presented as a space of sexual bohemia, with a freedom to dance and drink and explore that is cruelly absent from the rigid confines of the heterosexual world depicted elsewhere. The spectre of Aids on the horizon – the first reported case was declared just over a year after Cruising’s release – adds to the film’s unexpected sense of melancholy, even if only in hindsight.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

There’s also a curious subtext to Pacino’s character, who bears an uncanny resemblance to the killer’s victims, and who immediately returns home to have sex with his girlfriend at the end of each undercover shift. When he articulates to a superior his concern about being “in too deep” while undercover, it can easily be read as a sexually confused man shocked to discover what gets him off. The film’s famously ambiguous ending, with Pacino appearing to transform into what he most fears (either metaphorically or literally), only accentuates his character’s potential queerness.

While their hacky scripts prevent them from being genuinely great movies, Windows and Dressed to Kill have their virtues. The former is visually gorgeous, as Willis, a celebrated cinematographer whose work includes The Godfather, Manhattan and Klute, filled the screen with vivid blacks and crisp shots of autumnal Brooklyn. The latter, meanwhile, is nicely aware of its own griminess, its narrative failings eclipsed by De Palma’s stylish showmanship. It’s arguably the filmmaker in his aesthetic prime, full of OTT split screens, killer trans women in designer shades and porn star body doubles. Not a single person involved seems to take it seriously, which entirely rescues it.

Despite many of their failings, what is shared by all three movies is their embrace of outwardly queer villainy. Dangerous in 1980, it’s almost novel today. Queerness has always existed in horror genre antagonists, but historically it has been buried in the subtext. James Whale, one of Hollywood’s first openly gay directors, imbued his films with subtle queer themes, notably the zany flamboyance of Bride of Frankenstein. Few could argue that Rebecca’s Mrs Danvers, a tyrannical housekeeper fixated on the beauty of her former mistress, was anything other than a coded queer villain, while Psycho’s Norman Bates, a fey murderer who dresses up as his dead mother, was a gay, Freudian nightmare.

Cruising, Dressed to Kill and Windows are upfront about it all. Their villains are villainous literally because they’re queer, individuals pushed into madness by rejection and hostility – from objects of affection, from family or society at large. Viewed in 2020, they’re like something out of an alternate universe. Only Dressed to Kill still seems potentially destructive. One of the great sadnesses of its 40th anniversary is that many of its baffling misunderstandings of trans identity are suddenly relevant again. Even a decade ago, when trans people weren’t being so regularly villainised in the mainstream press, Dressed to Kill could have been described as harmless, its messaging so obviously ludicrous. That no longer seems the case.

It is, of course, for the greater good that American cinema shifted away from this kind of representation. By 1982, a year into the Aids crisis, major studios were producing films like the forgotten coming-out comedy Making Love, as well as the lesbian track-and-field drama Personal Best. More sensitive portrayals of queer life came later, via the moving Longtime Companion (1989) or the heavy-handed Philadelphia (1993), about a homophobic lawyer taught the error of his ways by a kindly gay man dying of Aids. Instead of being demonised, queer characters were humanised by their physical and emotional proximity to straight ones – the message evolved into “we are all the same”, ironing out much of the complexities or nuance.

It was progress, but also a vague form of assimilation. The queer sitcoms of the 1990s followed suit, with gay characters almost indistinguishable from their straight counterparts – be it the upper-middle-class domesticity of lesbian couple Carol and Susan on Friends, or Will of Will & Grace, a gay man depicted as respectable and elegant, whose “relatable” neuroses were so often contrasted against the loud, delusional queeniness of Sean Hayes’s Jack. Complex depictions of queerness, of a kind that could be sexy, violent or difficult, were confined to the fringes of film-making, via indie pioneers like Gregg Araki, Cheryl Dunye, Rose Troche and Todd Haynes.

On-screen queerness has become more nuanced in recent years, particularly via queer storytellers from Lena Waithe and Mae Martin to Jeremy O Harris. It remains elusive, though, to see queer villains of overt evilness in something that would ever touch a multiplex, studios often fearful to present queerness as anything other than resolutely “good”.

Even something as woeful as Windows seems radical as a result, awash with such extreme levels of ill-judged bad taste that it becomes glorious. Like Cruising and Dressed to Kill, it is offensive and shocking and deeply trashy. And nothing could be more queer.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments