‘Scorsese threw a desk over and ran out the room’: The tortured making of Gangs of New York, 20 years on

It took 25 years for Martin Scorsese to bring his passion project – based on a novel by Herbert Asbury – to the big screen, writes Tom Fordy. But not before a tumultuous production that saw him wage war against Harvey Weinstein and build a life-size recreation of New York

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

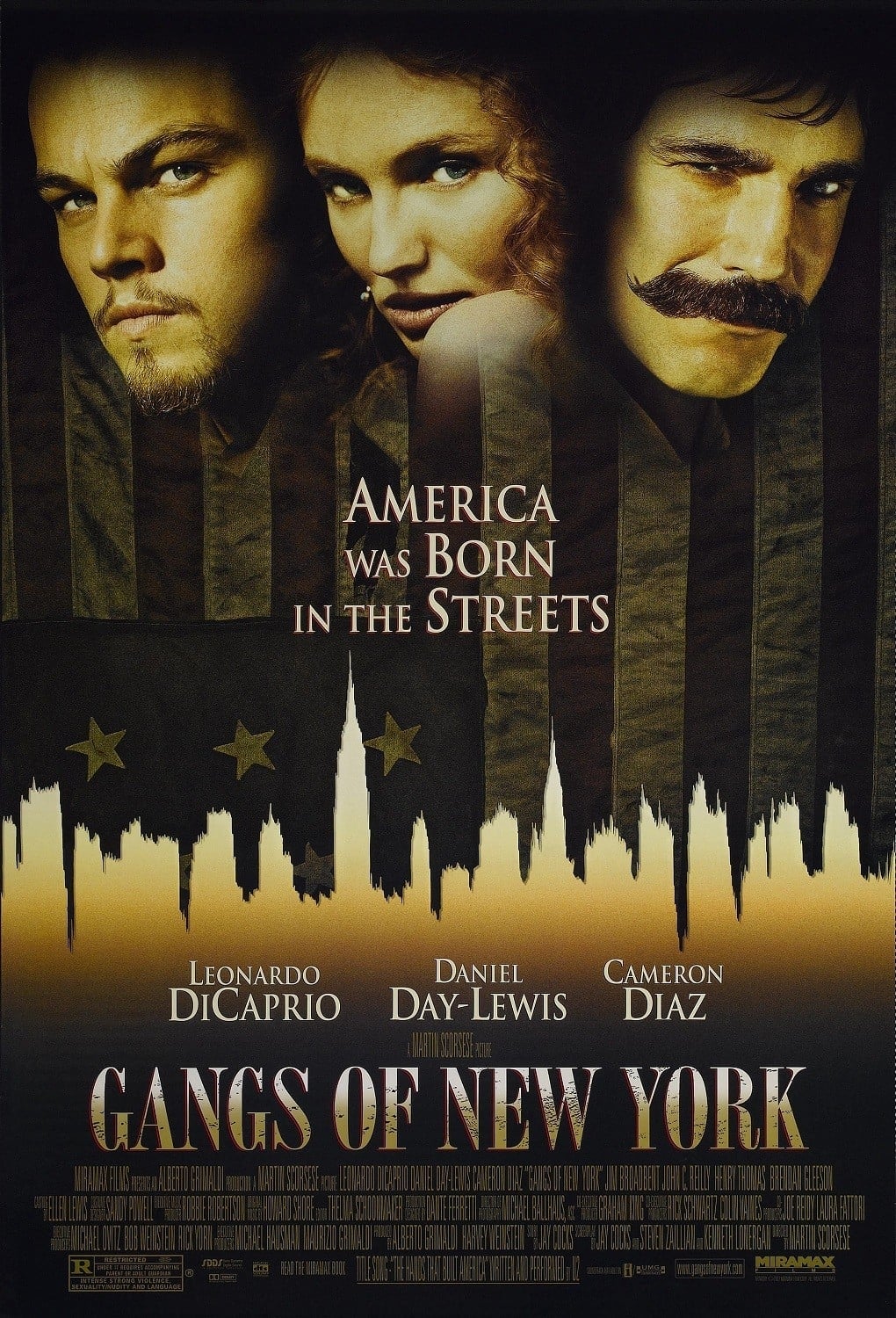

Your support makes all the difference.In June 1977, a two-page ad was published in the Hollywood trade magazine, Daily Variety. The ad announced a film that was about to go into production: Gangs of New York, from the hot thirtysomething director of Taxi Driver, Martin Scorsese. Based on a cult favourite book by Herbert Asbury, the film would be an epic tale about Five Points slum in 19th-century New York and the gangs who terrorised its streets. It would ultimately take 25 years to put Scorsese’s grand vision on the big screen. The film – starring Leonardo DiCaprio, Daniel Day-Lewis, and Cameron Diaz – was finally released on 20 December 2002, after decades of delays, a vast reconstruction of Lower Manhattan in Rome, and a series of spats between Scorsese and his since disgraced producer, Harvey Weinstein.

Now, 20 years since its release, Gangs of New York is a curious entry in Scorsese’s body of work. It’s something of a spiritual prequel to his contemporary gangster films, but oddly of-its-time, too – even Scorsese succumbed to post-millennium stylings.

For Martin Scorsese, Gangs of New York was personal. Growing up in Little Italy, he was fascinated by stories of gangs in his neighbourhood – in particular, a clash between American-born Protestants and Irish Catholic immigrants, which had taken place outside Scorsese’s local church in 1844. There were also clues dotted around – from weathered headstones to archaic cobbled streets – that gave him an inkling of what the neighbourhood might have been like 100 or more years earlier.

“I gradually realised that the Italian-Americans weren’t the first ones there, that other people had been there before us,” Scorsese told the Smithsonian in December 2002. “As I began to understand this, it fascinated me. I kept wondering, how did New York look? What were the people like? How did they walk, eat, work, dress?”

In 1970, Scorsese chanced upon the book, The Gangs of New York by Herbert Asbury. First published in 1927, the book detailed the gangs of Lower Manhattan – particularly in the Five Points, an area that encompassed an intersection of roads (where Chinatown now stands) named for its five corners. The Five Points – notorious for its crime, filth, and disease – was home to many immigrants, including Irish, who at times poured into New York at a rate of 15,000 per week. The amusingly named gangs were made up of Irish sluggers, or native-born, anti-immigrant Americans – the Dead Rabbits, the Plug Uglies, the True Blue Americans, the Shirt Tails, the Roach Guards and the Bowery Boys. Corrupt politicians used the gangs for their muscle and influence. The gangs helped fix polls or influence voting. According to Asbury’s book, gangs would feud and fight for days on end.

There was more at stake than a good beating. “The country was up for grabs, and New York was a powder keg,” Scorsese told the Smithsonian. “This was the America not of the West with its wide-open spaces, but of claustrophobia, where everyone was crushed together.” He added: “It was chaos, tribal chaos. Gradually, there was a street by street, block by block, working out of democracy as people learned somehow to live together. If democracy didn’t happen in New York, it wasn’t going to happen anywhere.”

Scorsese optioned The Gangs of New York and his friend, Jay Cocks – the critic-turned-screenwriter – finished the first draft of the script in 1978. The story, which went through many drafts and several additional writers, begins with a showdown between the Irish gang, the Dead Rabbits, led by Priest Vallon (Liam Neeson), and the anti-immigration Natives, led by the meat cleaver-wielding Bill “The Butcher” Cutting (Daniel Day-Lewis). Bill kills Vallon, as witnessed by Vallon’s young son, Amsterdam (who grows up to become Leonardo DiCaprio). Amsterdam returns to the Five Points years later to take revenge. He’s almost sucked into Bill the Butcher’s cult of personality, forming a strange father-son bond, before Amsterdam resurrects the Dead Rabbits and fights to the death with Bill.

Mixing historical fact and fiction, it’s set against the backdrop of the 1863 Draft Riots – a deadly, days-long uprising, looting, and lynching, which was sparked by the Civil War Draft. Bill the Butcher was based on Bill Poole, leader of the Bowery Boys gang and a member of the nativist Know Nothings political party.

Scorsese’s vision was simply too expensive. To bring the story to life, Scorsese needed to recreate – actually build – a significant portion of 1860s New York. “By 1980 the time when directors were given large sums of money to make personal movies had ended,” wrote Scorsese in a book about the film. He held onto the project though.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

In the early Nineties, Gangs of New York went into development at Universal. Robert De Niro, then Scorsese’s go-to man, was attached at one point, in line to play Bill the Butcher. The project then went to Disney, but Disney started to balk at the violence. (Even Scorsese – the director who put a mobster’s head in a vice – would struggle with that aspect. “The violence is tricky,” he told The New Yorker, “but that’s the way those characters behaved. I have to figure out how to shoot it”.)

It was also a few years since Scorsese had scored a box office hit. In 1995, Casino – an undisputed Scorsese masterpiece – was a disappointment in the US. Kundun and Bringing Out the Dead were straight-up box office duds in 1997 and 1999, respectively.

But with a $65m deal secured for international distribution, Miramax – a Disney subsidiary, then run by Harvey and Bob Weinstein – took control. In the book Down and Dirty Pictures, American critic Peter Biskind described how Scorsese was “a trophy director [and] Oscar bait” for Harvey. This was the time when the Weinsteins were establishing a grip over awards season. “Harvey was a kingmaker of actors and directors,” says Michael Hausman, executive producer on Gangs of New York. “In those days nobody wanted to cross Harvey – or his brother.”

Leonardo DiCaprio had first heard about The Gangs of New York when he was just 16 (about the age he made Critters 3). At 17, he changed agencies just to be in potentially closer contact with Scorsese. At the time, not everyone saw DiCaprio as an acting heavyweight. Following Titanic and The Beach there remained an air of heartthrob about his rep. That Scorsese has cast him (DiCaprio starred in Steven Spielberg’s Catch Me If You Can the same year) put him on a new level. In the 20 years since, DiCaprio has been Scorsese’s most significant onscreen collaborator, starring in five more of his films.

With De Niro long gone, Daniel Day-Lewis took the role of Bill the Butcher. Day-Lewis was typically intense: he shadowed a real butcher – “You never know what will help,” he once joked – and mastered the art of swinging a meat cleaver around. Day-Lewis stayed in character and “relished Bill’s companionship”. “I never met Daniel Day-Lewis on the movie,” says Hausman. “It was always Bill the Butcher. It was confusing! I’d knock on his door and have to say, ‘Bill, I’ve got a question for you…’ I saw him years later. I said, ‘It’s been five years, can I call you Daniel now?’”

They had written so many versions [of the script]! ... Sometimes [the cinematographer] had set something up and Marty would say, ‘No, we’re doing it from another direction!’

Liam Neeson – who played Priest Vallon, slaughtered by Bill in the opening battle – played a game of one-upmanship with Day-Lewis. Neeson found out that Day-Lewis went to the gym at 5.30am, so he started getting there at 4.30am – so as Day-Lewis was coming in, Neeson was leaving.

Day-Lewis saw Bill the Butcher as “a hooligan dandy”. Indeed, with his stovepipe hat, swish tailoring, and American eagle glass eye, Bill is a moustache-twirling cartoon villain. But one sketched upon the film’s melting pot of themes: political fury, corruption, patriotism, pride, racial tensions, history, the making of democracy.

He wasn’t the only one taking it intensely. Screenwriter Hossein Amini, who worked on two drafts, recalled two days of 12-hour meetings with DiCaprio, just talking about character and dialogue. DiCaprio said his prep also included “weight training, knife throwing, and various fighting methods from the period”.

There was lots of historical research done – though the film isn’t strictly factual – and the production was designed to be real and period accurate. As well as Herbert Asbury’s book, they relied on Lucy Sante’s Low Life, about old school Manhattan, and the Rogue’s Lexicon, from 1859, for period-specific slang. For the myriad of accents, the actors turned to dialect coach Tim Monich. The big challenge was creating the accent for working class native New Yorkers in the 1860s, for which there was very little historic evidence to emulate. Listening to a recording of poet Walt Whitman, Monich decided it wouldn’t sound all that different to a 20th-century Brooklyn cab driver.

Watched now, Gangs of New York boasts an impressive cast. Alongside Day-Lewis, DiCaprio, Diaz, and Neeson are Jim Broadbent, John C Reilly, Brendan Gleeson, Stephen Graham, and Henry Thomas – then best known as Elliot from ET. The real star, however, was 1860s New York, including the Five Points, which was recreated at the Cinecitta Studio in Rome, Italy. Production designer Dante Ferretti constructed more than a mile of buildings – essentially several blocks of Lower Manhattan. The Five Points got very real. “After we’d had a couple of storms, which had etched their own character into the streets, the cobblestones turned to muck,” says Day-Lewis. “I just love that place. I loved being in it. It was my home.”

The set was so enormous that when Scorsese began shooting, there weren’t enough extras to fill it. Michael Hausman, who spent 16 months on the film and was there for the entire shoot in Rome, recalls being called to the set by Scorsese on the very first day of shooting. “I get there and he plays the last take,” says Hausman. “He said, ‘The set looks empty!’ I told him, ‘Dante Ferretti built a set too big, of course it looks empty!’” Scorsese also complained that the extras looked too Italian – that none of them had blue eyes. “Well, Marty, they are Italian!” said Hausman. “They have big Italian noses and brown eyes… I don’t know what to tell you.”

That night, Hausman had to trawl the American, British, and Irish Embassies, asking people with blue eyes if they wanted to be in a movie next to Leonardo DiCaprio.

The production dragged on, ultimately going eight weeks over schedule and adding a reported $20m to the budget – from $83m to a reported $100m-plus. Hausman recalls how slow-going the process could be. Before filming every day, Scorsese would disappear into his office and decide which version of the script to shoot. “They had written so many versions!” laughs Hausman. “That was a real delay, until they came on set and said, ‘We’re gonna shoot this version or that version.’ Sometimes Michael Ballhaus [the cinematographer] had set something up and Marty would say, ‘No, we’re doing it from another direction!’”

While the Five Points was the setting of the film’s major battles, there was a clash behind the scenes, too: Martin Scorsese vs Harvey Weinstein. There were reports of numerous points of friction, such as Weinstein turning up on set and harrying Scorsese to work faster; or that Weinstein was unhappy with Day-Lewis’s less-than-attractive get-up in the film, which he claimed just wouldn’t look good on a poster. (Day-Lewis himself didn’t like Weinstein. “What he doesn’t understand is that I did Gangs in spite of Harvey, not because of Harvey,” Day-Lewis later said.)

It was Hausman’s job to represent Weinstein’s interests on the set, and he was responsible for setting up – and mediating – meetings between Scorsese and Weinstein. Hausman had to vet Weinstein’s questions for Scorsese beforehand, then rehearse the answers with Scorsese to give to Weinstein. “If he started mentioning anything not on the list, I would tell Harvey, ‘Don’t finish that sentence or Marty is going to disappear! The meeting’s gonna be over.’”

Among things that Weinstein didn’t like was the Dead Rabbits gang name. But Hausman warned him: don’t bring up the Dead Rabbits name; both Scorsese and DiCaprio loved it. But during a meeting with Weinstein’s assistant, the topic came up. “When the meeting started, the first thing out of his mouth was that Harvey doesn’t like the name, Dead Rabbits,” says Hausman. “Marty went over and threw a desk upside down – with a PA’s computer on – and ran out of the room. We didn’t see him for the rest of the day.”

The film was scheduled for release in December 2001, but was delayed. By April the following year, the New York Times reported that Scorsese and Weinstein were at war. The rough cut had come in at three hours and 40 minutes, with Scorsese apparently considering reshoots. For Scorsese, Gangs of New York was 25 years in the making; he wanted to realise his artistic vision in full. Weinstein, however, wanted a more streamlined, commercial film. “I’m a producer and producers always want movies under two hours,” says Hausman. “So you can get more screenings in a day.”

Publicly, Scorsese and Weinstein maintained that they had a “terrific working relationship”. Weinstein wanted it for Cannes in May 2002, though it didn’t arrive until December. Weinstein also relented and moved the film back a week, to prevent it going head-to-head with DiCaprio’s other big movie, Catch Me If You Can.

Reviews, like the film itself, were good but occasionally uneven. The New York Times called it “a near-great movie” that would “make up the distance” over time. Day-Lewis, it said, positively luxuriates in his character’s villainy and turns Bill’s flavoursome dialogue into vernacular poetry.” The Independent called it “a breathtakingly strange, genuinely savage vision” but also “ragged and misshapen”.

Gangs of New York was nominated for ten Oscars, including – regrettably – the U2 tie-in song, “The Hands That Built America” – and made a respectable $193.8m [£310m]. Stood next to Goodfellas and Casino, Gangs of New York seems dreamlike. There’s plenty of muck, grit, and viscera, but it’s otherworldly, hellish, and grotesque, too. It’s a Victorian sideshow of violence. It is, as Bill the Butcher might say, a “spectacle of fearsome acts”. Indeed, both Bill and the violence are thunderous: faces mashed in; ears torn off; cleavers lobbed into the backs of political rivals.

There is an irony to how long it took to get Gangs of New York made. It’s a film set in the 1860s and which took 25 years to bring to cinemas. Yet it’s somehow aged in ways that other Scorsese films haven’t. It’s less to do with the quality of filmmaking, more the cultural moment. It permeates with early 2000s-ness – a score that feels just one sample away from Moby; the of-the-moment casting of Cameron Diaz, who struggles through a notoriously haphazard Irish accent; and a pace to its action that, just like Bill the Butcher’s tailoring, now seems out of trend.

Yet, Gangs of New York has as much to say about the modern world as 1860s New York. “Civilisation is crumbling,” says Bill, with the American flag draped around his shoulders. “God bless you.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments