Marvel is tired, Star Wars is self-parody – now Mad Max is the last franchise standing

Ahead of the release of ‘Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga’, Geoffrey Macnab explores how Aussie director George Miller masterminded one of cinema’s wonderful anomalies

When George Miller was starting out as a filmmaker, he was known as “Doctor George”. It’s one of the many paradoxes about Miller that the 79-year-old Aussie – ranked by many among the finest action directors in movie history – began his career in medicine. Since his early days working alongside producer partner and “filmmaking brother” Byron Kennedy (who tragically died in a helicopter accident in 1983), Miller has been uncompromising about health and safety. Not that you’d know it by watching his films.

There were no reported serious accidents or injuries during the shooting of Miller’s new feature, Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga (premiering in Cannes this week) – a remarkable feat, given the film’s frantic, stunts-heavy ethos. After all, Miller likes his action scenes to be as realistic as possible. He’ll hire Cirque du Soleil gymnasts to perform gravity-defying stunts rather than try to trick the audiences with visual effects. Like its predecessors, the new movie is awash with blood, carnage, mayhem, decapitations and disembowelling.

In one extraordinary 15-minute sequence that took a reported 78 days to film, Tom Burke as the legendary “rig driver” Praetorian Jack is shown behind the wheel of a huge oil juggernaut driving at breakneck speed down the desert road. The vehicle is being pursued by assailants on all sides, some of them paragliding high above it, others on motorbikes or in trucks. Furiosa herself (Anya Taylor-Joy) is clinging to the undercarriage, trying to stop the vehicle from blowing up. It’s like a hyper-charged version of a stagecoach chase in an old western. Such high jinks are what audiences have come to expect from a Max Max movie – but are only a part of what has turned the series into such a phenomenon.

“First and foremost, he [Miller] is very, very intelligent,” Iain Smith, executive producer of the 2015 franchise instalment Fury Road, tells me. “He’s a man of enormous focus and passion to make a small idea grow and become a big thing. The Mad Max series is a great example of that.”

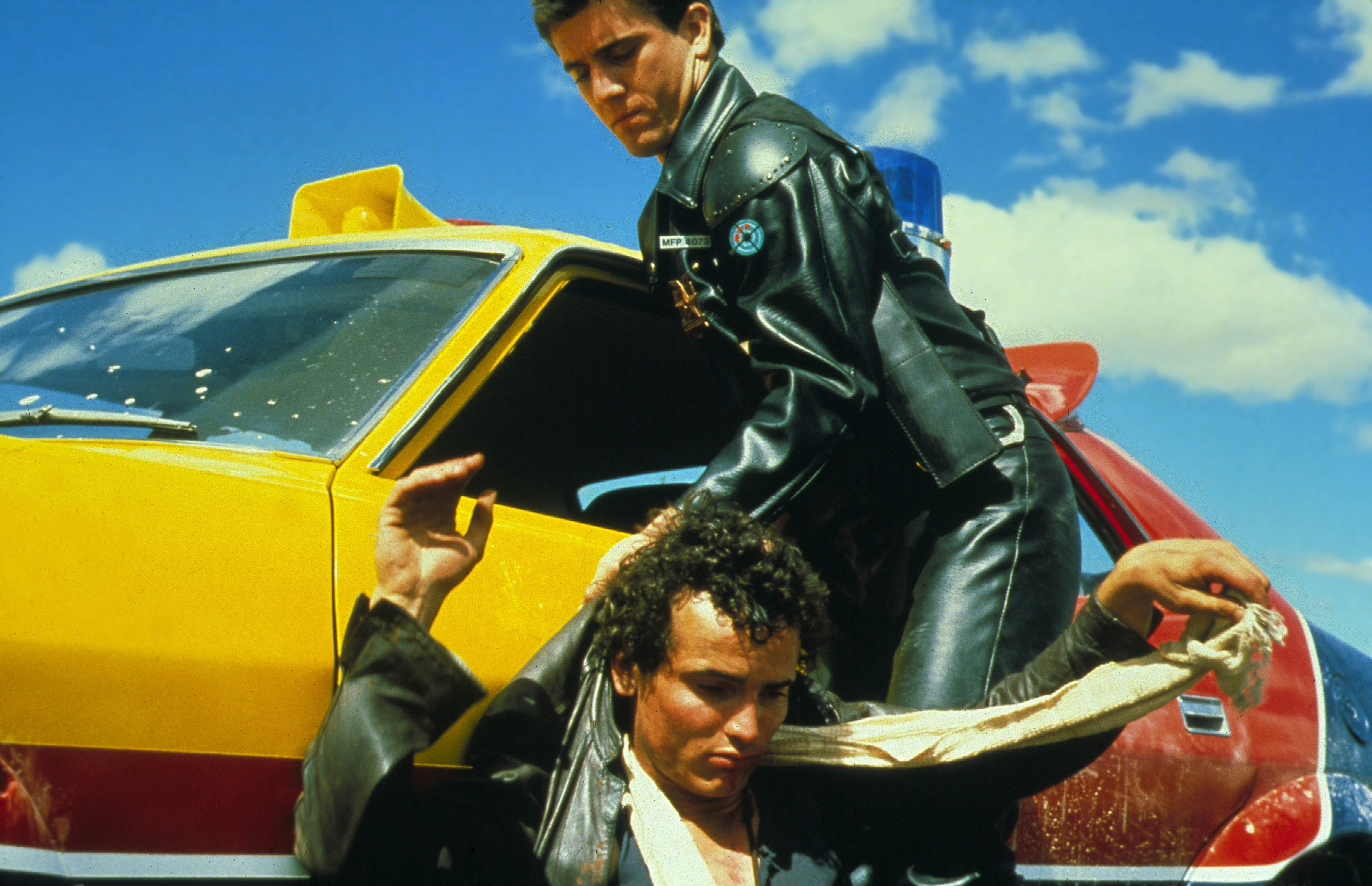

This is indeed one of recent cinema history’s most unlikely metamorphoses. Over 45 years, what started as a grungy, low-budget Australian exploitation pic has gradually evolved into a massive franchise. The first film, Mad Max (1979), was very modest in scope – an Aussie version of one of those genre movies that the late Roger Corman was so adept at making. Its budget was around $2m – that’s to say, around $170m less than is thought to have been spent on Furiosa. The production values were closer to those of an episode of TV’s The Dukes of Hazard than they were to the blockbuster movies that Miller is overseeing today. The director’s fabled post-apocalyptic “wasteland”, where packs of renegades are fighting for survival, looked unmistakably like the Australian outback.

Mad Max was dubbed for international audiences. US distributors worried that viewers simply wouldn’t understand the Australian slang of the actors, including the 21-year-old pre-fame Mel Gibson. Nonetheless, the project’s ambition and mythic dimension were evident from the outset. The first film had all the crashes, sex and violence that you expected in films from the “video nasties era” but with a lot more under the hood. Miller was asking some very unsettling questions about how quickly the veneer of civilisation can be stripped away when the food and fuel run out.

“George is deeply Australian… he’s not interested in stereotypes. He’s more interested in the archetypes,” Smith says. “The archetypes he found in Australian stories and Australian people inspired Mad Max in the first place. The sense that the world has been screwed up and they now have to be out there on their own is a very Australian idea in many ways.”

The franchise consists of five films made over 45 years – and with a 30-year gap between the third instalment, Beyond Thunderdome, in 1985 and the fourth, Fury Road, in 2015. During that hiatus, Miller left the savagery of the Wasteland far behind, taking on family fare like Babe: Pig In The City (1998) and Happy Feet (2006) instead, while also directing Jack Nicholson as a diabolic seducer in the adaptation of John Updike’s The Witches of Eastwick (1987).

When he finally came back to Mad Max in the late 1990s, Miller refused to be pushed around by the studios. Warner Bros tried to assert ownership over the franchise – something he was never going to accept. He therefore looked to Fox for backing but plans for a new film were scuppered by 9/11 (“we couldn’t get insured, we couldn’t get our vehicles transported. It just collapsed,” the director told The New York Times) and later by the personal problems that overtook the star, Gibson, who fell from grace in spectacular fashion after being caught making drunken antisemitic rants.

Warner Bros eventually came back into the fold and Miller was finally able to set off deep into the Namibian desert to make Fury Road. Smith talks of the director’s intensity, single-mindedness and “intrinsic sense” of storytelling, but also about his flexibility and ability to work on the hoof. “He wasn’t a flummoxer,” he says. “He wasn’t somebody who changed his mind every week. One of the great things about George was that despite all of the years of preparing for this, he still maintained an openness at the point of shooting.”

Miller makes Max Max films from illustrated storyboards rather than from a conventional script. On Fury Road, there were well over 3,500 of these.

“My favourite dictum from Hitchcock, who knew more about film language than anyone else, was to try to make movies where they don’t have to read the subtitles in Japan,” Miller said, explaining to podcaster Justin Horowitz why he always privileges imagery over dialogue. “It [filmmaking] is visual music.”

Gibson became a huge star on the back of Mad Max but in the first film, he says very little. The same terseness applies to Tom Hardy and Charlize Theron in Fury Road, and Anya Taylor-Joy, who has only a handful of lines in Furiosa. “Mouth closed, no emotion, speak with your eyes,” is how she recently summed up the director’s instructions to her. Nonetheless, like an old silent movie star, she is still able to give a marvellously expressive performance.

Miller wasn’t a luvvie kind of director. He wasn’t chumming up and trying to be their best friend. He was a definite leader of the pack

Miller is a master psychologist who understands what makes actors tick. But that doesn’t mean he makes it easy for them. “I’ve never been more alone than making [Furiosa],” Taylor-Joy recently told The New York Times. “I don’t want to go too deep into it but everything that I thought was going to be easy was hard.” Hardy, meanwhile, was famously baffled about the director’s process on Fury Road – and ended up apologising to the director at the Cannes press conference, saying that once he had seen the film, it all finally made sense. “It was a nightmare. A brilliant nightmare, and confusing. You’re not really in a movie. You’re in George’s head,” he later said.

“[Miller] has a slightly arm’s-length relationship with his actors, a little bit in the Hitchcockian tradition I would say. Both Charlize [Theron] and Tom [Hardy], he handled differently,” Smith says of the stars of Fury Road. “This intelligence he had was the thing that was driving it. He could manipulate the situation to the point where he got what he wanted. He wasn’t a luvvie kind of director. He wasn’t chumming up and trying to be their best friend. He was a definite leader of the pack.”

Theron and Hardy didn’t get on and had very different approaches to their craft. Former ballet dancer Theron was disciplined, punctual and precise. Hardy was more “method” and liked to explore and improvise. (He did his own stunts despite a fear of heights.)

“George handled both of those extremes extremely well,” Smith suggests. “I don’t know how deeply Tom or, for that matter, Charlize took his essays seriously but he would issue these very profound essays on what Mad Max was about and why we had to understand the mythic aspects of the story.”

As exec producer, Smith was caught between the director and the studios. “A lot of what I had to do was to keep the studio calm and keep them well informed every single day of how well we were doing so he could continue without being messed around.

“They [the studios] know he can pull it off. They know he has the capacity to make something very unusual and powerful… he doesn’t very much like having studio executives around. So Warners were rather nervous, even though they knew they had a very valuable asset in George.”

On most big-budget movies, the studios are given cost reports every day. This was almost impossible on Fury Road because of Miller’s unusual working methods.

“The studio got very irritated because they didn’t have the usual 150-page script…the script is used as a measuring device for executives to mark off what has been achieved and what has not been achieved. It’s part of a contractual understanding of who promised to do what, when and how,” Smith says.

Working with Miller required a huge leap of faith from the financiers. They don’t know exactly what is happening out there in the desert during production and they have to wait a small eternity for a completed film to be delivered. On Fury Road, Miller had shot an astonishing 450 hours of dailies. Smith says, though, that he was utterly clear in what he wanted – even if the studio was “freaking out” by then about Miller going over budget (according to The New York Times). Production wrapped without Miller having filmed the beginning or end, and only a change in the top brass at the studio enabled him to do the reshoots needed, months later.

Part of what draws viewers to the Mad Max universe is its thematic richness. Every truck and motorbike has its own mythology. Every prop, wig or helmet is painstakingly crafted. In his plotting, Miller draws on everything from Greek tragedy to A Clockwork Orange.

The stories are always brutal. The protagonists experience extreme physical hardship but they never quite lose their humanity. Nor (despite Tina Turner’s casting in 1985’s Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome) does the storytelling ever quite slip into kitsch.

At a time when all those Star Wars epics and their spin-offs are feeling increasingly self-parodic and audiences are developing acute superhero fatigue, Mad Max is arguably the only major franchise that isn’t currently showing signs of rust. Whether you’re just there “for the gasoline” (in the parlance of Mad Max 2) and watch the movies purely for high adrenalin action kicks, or you buy in fully to Miller’s vision of a bleak, violent future, these are still films with a truly seismic charge.

‘Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga’ premieres this week at the Cannes Film Festival and is in UK cinemas from 24 May

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments