Director Eugene Green interview: 'My shoots are always a very joyous experience for everyone'

It took a long time for the US-born French filmmaker to find success. He tells Geoffrey Macnab about finding comedy in tragedy, his love for all things Baroque and why he feels like an alien in his country of birth

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Eugène Green is reaching for the correct word in English. In a heavy Gallic accent, he apologises when the word eludes him.

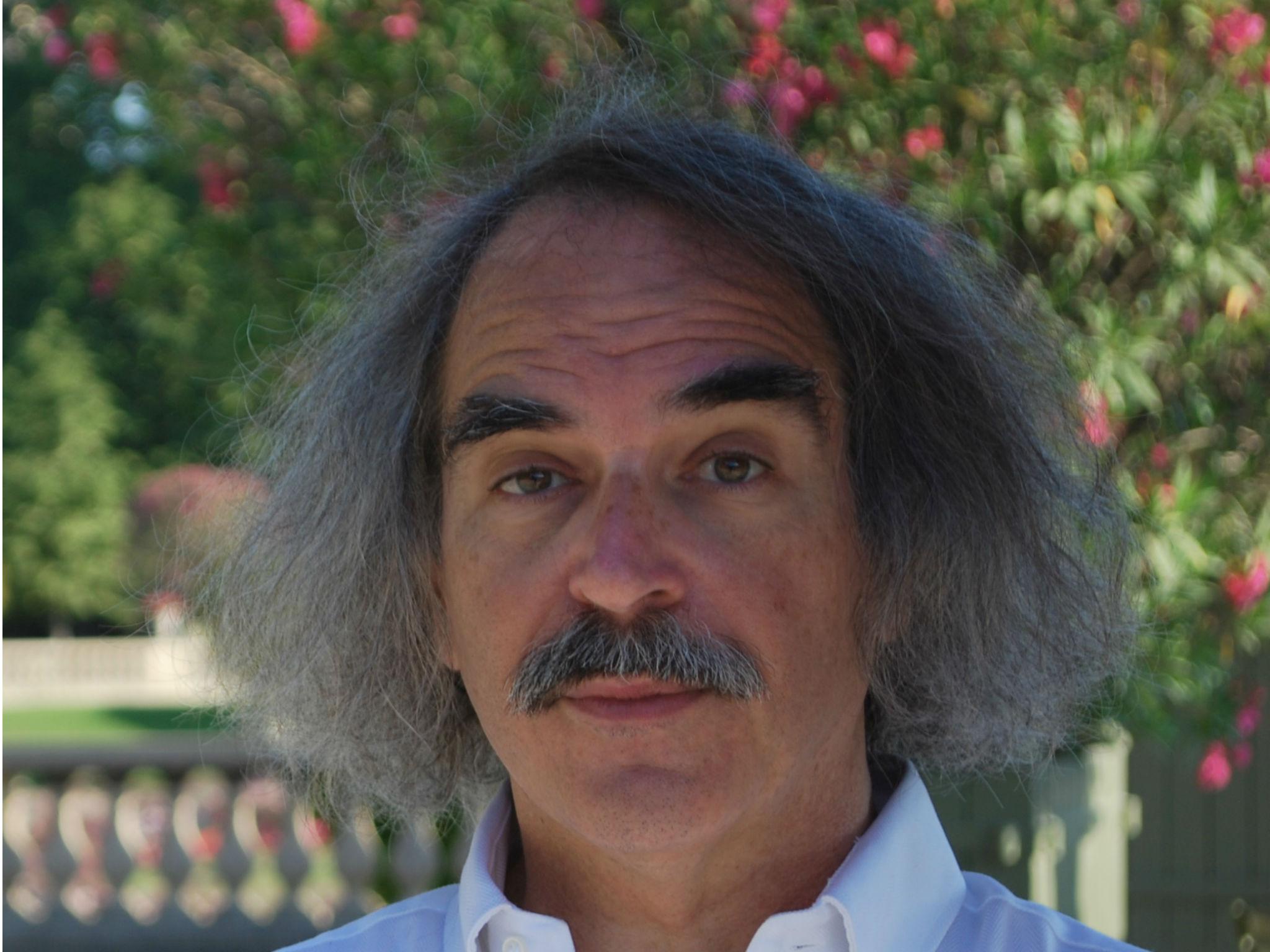

You won’t meet a filmmaker more French than Green. With his bushy shock of hair and grey moustache, he looks like a French professor.

Green is, in fact, from Brooklyn and moved to France only when he was a young adult. Nothing, though, irritates him more that to be reminded of his US roots. He can’t even bring himself to mention the name of the country in which he was born. (He prefers to call it “Barbaria.”) Green has a grave accent on the second “E” of his Christian name. He thinks in French, he dreams in French, and his US childhood is just a distant and unpleasant memory. He recently returned to the US for a screening in New York of his latest movie but felt as if he was on Mars. “I feel very alien there.”

Back in the 1960s, he had escaped the country at the earliest opportunity.

“I knew I was going to leave from the age of 11 on – but, at 11, I couldn’t leave,” the director says of his yearning to get away. “I realised very young, even younger than 11 years old, that man exists by language … and the Barbarians have no language. What they use to communicate is good for commerce but it is not English.”

Green talks darkly about the obsession with “consumerism and business” in America and the debasement of the language. When you try to press him about his family background or why he so despises the US, he clams up. He says that he is from a “modest” background and that his parents were “rather poor” but then adds: “I am not here to talk about Barbaria.”

One detail Green does give is that as a kid, he steeped himself in literature. He loved Shakespeare and thought for a time about coming to Britain. In the event, when he reached young adulthood, he headed first to Munich instead as he knew German better than French. He didn’t like Germany, though. It was only two decades after the end of the war and he found the atmosphere oppressive. Young people were tight lipped about what their parents had done in the Nazi era. The evasiveness and secrecy he encountered were major themes in one of his novels, La Reconstruction.

In this period, Green travelled widely across Europe. He was in Czechoslovakia at the time of the Prague Spring in 1968 but eventually headed to Paris, primarily to learn French. These were the heady days of student riots. He didn’t think he would stay for more than six months or so – but almost half a century later, he is still there. (He took French citizenship in the mid 1970s.)

In his time in France, Green has become one of the acknowledged experts on French Baroque theatre, writing extensively about it, performing it, teaching others about it and drawing on it in his filmmaking. His movies are very disconcerting affairs. They’re set in the present day but the actors recite their lines in a clear, formalistic fashion as if they’re actors in a 17th century play, addressing the audience directly.

His latest feature, The Son Of Joseph (which premiered in the London Film Festival this autumn), is about an adolescent in search of his father. Vincent (Victor Ezenfis) is a disgruntled teenager who has been brought up by his single mother, long-suffering nurse Marie (Natacha Regnier). She has refused to reveal the identity of his father but through his own sleuthing, Vincent works out the man in question is a conceited, womanising and entirely self-centred publisher called Oscar Pormenor (and played in wonderfully sleazy fashion by former Bond villain, Mathieu Amalric).

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

The film works both as contemporary comedy drama and as biblical allegory. That, the director explains, is precisely what makes it Baroque.

“In the middle ages, the Renaissance, there was no conflict between the scientific exploration of the universe and spiritual belief,” he explains. People believed that “the world was created by God and that he was visible in his created world”. Then, during the “Baroque period” of the 17th and early 18th century, many people lived in what Green describes as “an oxymoron”. They lived in a rational world, governed by natural laws, and yet they still believed that the “highest reality was God”.

Green tries to reconcile similar contradictions in his own life and work. “I have spiritual needs and, at the same time, I live in the modern world which is governed by reason, machines and robots now.”

The Son Of Joseph is far more playful than Green’s musings about science, religion and the nature of Baroque performance may suggest. There are scenes that wouldn’t look out of place in a Ray Cooney farce. At one point, Vincent is hiding under a chaise longue in his father’s office with an ankle eye view as his father is seducing the secretary.

“My shoots are always a very joyous experience for everyone,” Green insists.

One of the paradoxes about Green’s films is that they seem so high minded and yet are also so humorous. “It comes naturally to me,” he says of the irony and slapstick, the mix of farce and tragedy, that you find in his work. In France, he says, this humour is sometimes misunderstood. “They don’t like to mix things.” However, he sees jokes as serving a double function. “They relieve the tension while at the same time they increase it.”

These days, Green is a respected writer and filmmaker with a string of features behind him. Early on, he admits, it wasn’t easy to gain recognition. When he was first started writing plays in France, he was rejected by the theatre establishment. The plays were rarely staged. The best he could manage was a few public readings. He also performed at “Baroque” music events. “I was never very rich but I managed to survive.”

Then came the “miraculous opportunity” to make his first feature film. He’d long dreamed of becoming a filmmaker but had no contacts in the French film industry, although he was once taught by legendary French auteur Éric Rohmer when he was studying art history at the Sorbonne in the 1970s. “I liked him [Rohmer] but I was the only one [who did].” In this period, Rohmer’s films were thought to be reactionary by the radical young students. “Also, at that time, students liked to smoke in the lecture hall and he wouldn’t let them smoke – so they considered him a fascist.”

Rohmer gave Green top marks for his essays. Nonetheless,it wouldn’t be until many years later that Green managed to emulate his teacher and direct movies himself. In his mid-40s, he had the idea for a feature based on an early Flaubert novel. No one wanted to back him. He ended up putting his script, which took two years to write, in a drawer.

Eventually, the mood at the funding agencies changed. One of his earliest champions and patrons was the French filmmaker Jacques Rozier, who had seen and admired his stage work. Even though he didn’t have a producer or any practical filmmaking experience whatsoever, Green received a public loan to make the movie through the system of “avances sur recettes”. This was how his first film, Toutes Les Nuites (2001) came into being. Since then, he has completed several new features and has become an established figure in French cinema.

Green is passionate about the paintings of Caravaggio, a major influence on his films. “He represents to the highest degree Baroque painting,” he enthuses. “The hidden god is always present in his painting, represented by light that comes from a hidden source. For me, that is the basis of Baroque art.”

The director has a cameo as a hotel concierge in The Son Of Joseph. This is both another nod in the direction of Baroque art (Baroque painters would throw in references to themselves in their work) and a matter of necessity (there was no one else available to play the role.) It’s also an expression of humility as much as of egotism. (In previous films, he has played a waiter and a barman.)

Ask Green if he now considers himself to be French and if he has managed to expunge every trace of his American roots and he answers in the affirmative. “It is much easier for me to talk about intellectual things in French,” he says as his interview, conducted in an upmarket London hotel, draws to a close. “The first time I had to speak about the film in English, it was really very difficult,” he says. At least, he doesn’t feel as much of an outsider in Britain as when he was back in the USA. “When I was in New York, the relationship to the English language or whatever it is they speak there – I really feel very, very foreign. But here [in Britain], there is something in the language which touches me.”

‘The Son of Joseph’ is released in the UK on 16 December

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments