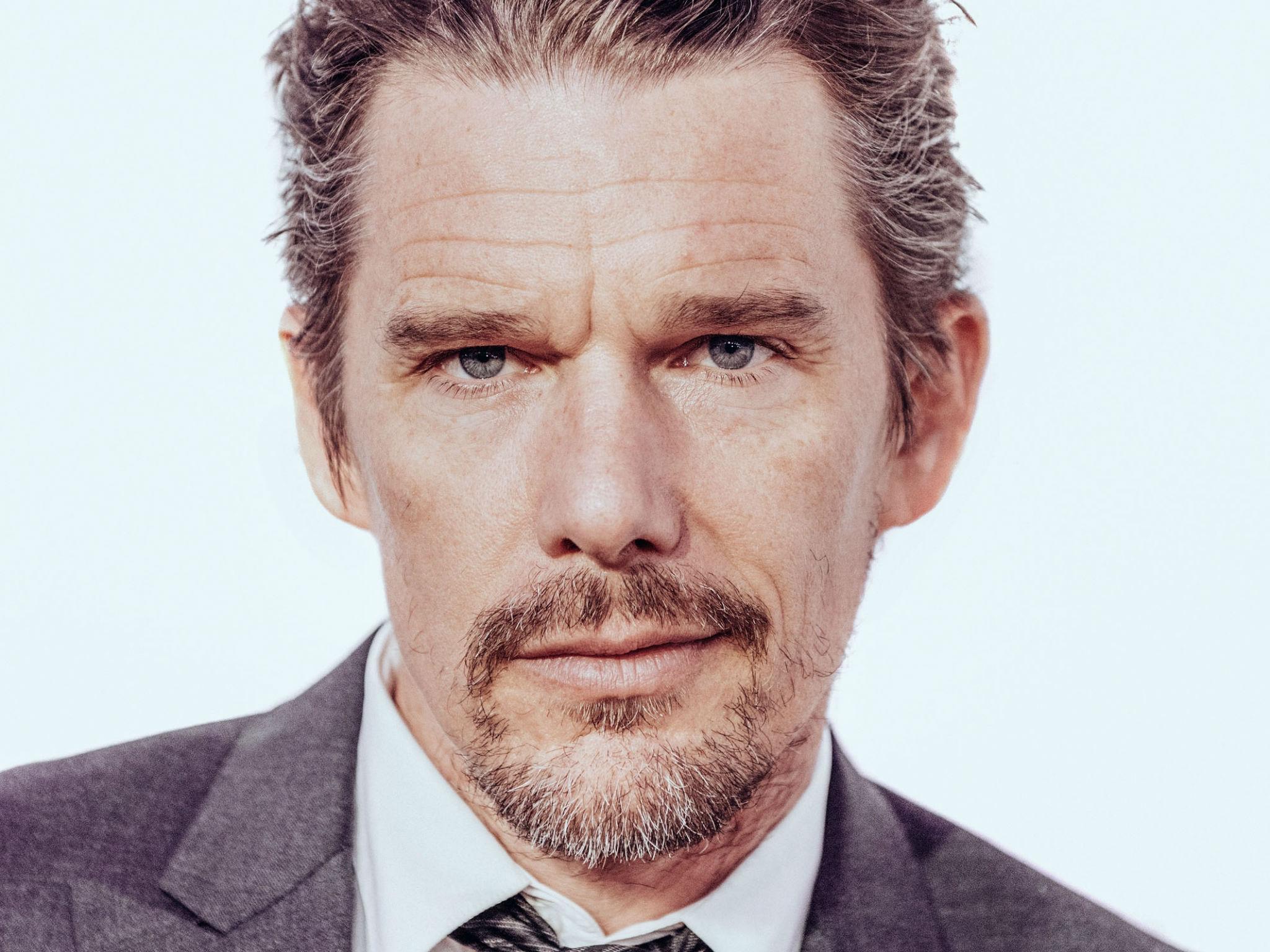

Ethan Hawke interview: 'I have a lot of hope for Jesse and Celine'

We sat down with the actor to dissect the trilogy he considers his most personal

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The sincerity of Ethan Hawke isn’t exclusive to his performances. Sitting in a London hotel on a Friday morning, the actor’s outlook matches the weather outside: warm and inviting. Perhaps no surprise considering this is an actor whose past credits include – sure, films where he plays characters of intense depth – primarily affable roles ensconced in reality.

Hawke can add another performance to that list with most recent film Maudie, a biographical tale centred on artist Maud Lewis, played by Sally Hawkins. Hawke plays her husband, Everett – a role he accepted due to his fondness of the shoot’s location: Canadian island, Newfoundland.

Conversation with Hawke naturally flowed to his working relationship with Boyhood filmmaker Richard Linklater. It swiftly emerged the actor was comfortable sharing his personal views on characters Jesse and Celine (Julie Delpy), the relationship at the heart of the Before trilogy – “films deeply connected to my soul,” he tells me – and in what capacity the world could see them reunited on-screen one day in the future.

You can find a recording and full transcript of the interview below.

We met before when you were promoting Good Kill.

It’s funny, I was actually thinking about Good Kill this morning because the whole political landscape is so changed. Movies are kind of dictated by the time and the moment they come out, and nobody was interested in politics when that came out [2014], nobody wanted to talk about it – we were all in a happy haze where we didn’t want to think about drone strikes or uncomfortable things. I was imagining that if Good Kill came out today, it would fare a lot better because politics is having a different place in our dinner table conversations than it was four years ago.

Do you think about your films in that context a lot?

Well, you see the power of the zeitgeist and how it moves around. Like, when Gattaca came out [in 1997], the zeitgeist wasn’t interested in that movie. But over ten, fifteen years, it comes up all the time, people always want to talk to me about it. Whereas a film like Boyhood (2014) hits the zeitgeist – it’s somehow what we wanted to be talking about then. The success of a movie is dictated – obviously by the quality – but it’s also an intersection of what people want to be thinking and talking about. Sometimes you’re in the right place at the right time and sometimes you can’t get anybody to sit and listen to you.

I’m glad you mentioned Gattaca – that film has really endured.

My gauge is what people want to talk to me about. Movies are different than theatre because when you’re in the theatre, you have a direct relationship with the audience. But I wasn’t there when you watched Gattaca. If you see me in a play, we’re in a room together. But movies that people want to talk to me about – that’s my relationship to the audience. I had a cop pull me over the other day – this is a strange story – but I did this movie that very few people have seen called Predestination. It’s about time travel and stuff, and a cop actually pulled me over and was like, “Sorry to bother you, I just had to ask you: what happened at the end of that movie?” [Laughs]. So I’m watching Predestination establish a cult status because the audience has a mysterious relationship with it. It was the most illegally downloaded movie of its year so it’s not exactly box office, but it’s something.

You’re very much an audience’s actor – if you’re in a film, people will want to go and see it regardless of whether they even wanted to in the first place.

Oh, that’s nice of you to say. I think that if any human being in any profession, whatever amount of time they spend thinking about their status is in direct proportion to what kind of blowhard jerk they are. I think Donald Trump spends a lot of time thinking about his status and it’s exactly why I wouldn’t want to be at a dinner table with him.

Which of your many films has stayed with you the longest?

The Before trilogy… Boyhood and the Before trilogy are deeply connected to my soul for lack of a better word. I’ve worked on Jesse, which is the main character from the Before movies, at nine-year intervals. I started working on that character when I was 25 and the last time when I was 41, so it’s been with me and I’ve gotten to put a lot of my own life into those movies. Boyhood is only short a couple of years – it was 12 years working on that character. So those movies are part of me in a way that other movies are one window. Training Day (2001) was an important moment in my life [Hawke was Oscar-nominated for Best Supporting Actor] but it was just a short little window. I did this movie with Richard Linklater called Tape (2001) that very few people have seen but that, for me personally, was kind of a breakthrough for my creative life, for taking acting to a more grown up level.

You’ve worked with several directors on numerous occasions [Andrew Niccol and Antoine Fuqua included] but would you describe your working relationship with Richard Linklater as your most defining?

Well, yeah – I’ve done nine movies with him. It’s a lot. I’ve done three with Andrew, I’ve done three with Antoine, I’ve done two with the Spierig brothers. I’ve worked with a bunch of people twice. I’m proud of that, working with people again because being creative together is hard but if it goes well you can get into the next room with each other. For example, I finished Before Sunrise (1995) and I felt ready to start it. You get to a level of intimacy, you get into the deep end of the pool and you’re like, “I wish we started here”. Well, on Before Sunset I got to; we were already in it. With Antoine and Denzel it’s the same thing – you get to skip the boring five weeks of getting to know you and dive right in. I like that.

I interviewed Linklater last year [you can find it here] and he mentioned how he views the Before films to be a Rorschach test for couples

I agree. I did an interview with a guy at The New Yorker about Before Midnight (2013) and he found the movie so depressing. I remember saying, “Man, that’s something you’ve got to think about.” Because I meet other people that find the movie absolutely uplifting. I explained that to him and he said, “Nobody finds that movie uplifting” – that’s not true; people who are happily married find it uplifting. It stopped him. All three of those movies in their own way are their own Rorschach test about where you are… Before Sunrise ends with them saying, “Let’s meet again in six months.” People who believe in love think they’re definitely going to meet again. People who are deeply cynical or carrying a lot of hurt around with them are like, “That’s over.” The ending of Before Sunset (2004) is its own zen koan, he’s missing his plane and everything. But Before Midnight is definitely the hardest of the films because both the other two films deal with romantic projection and the third film deals with romantic reality. I’ve always found it a deeply optimistic film because of how engaged with each they are. People often think that because people are fighting, something bad is happening, and, often times, the opposite is true. If I look back at my own life, and I see the most hurtful, scratchiest parts, those are the parts where the most growing had happened. At the end of Before Midnight, I have a lot of hope for Jesse and Celine because at least they’re not living a lie – they’re engaged with each other. It’s a hard relationship, for sure, but I see a lot of love in that movie.

Do you think that Jesse has hope for his and Celine’s marriage?

[Pause] Yeah, at the end of that movie, I think he has more hope than Celine does. The thing that I find interesting about the trilogy itself is that the first film – you have to geek out at the movies to care about this – but in the first film she’s the more romantic one and he’s cool and more interested in his career and life and trying to be… I don’t know what, but it’s not romance. In the third film, and I think this is true of how a lot of the women I know, she’s looking square in the eyes of how tough the world is for being a woman and that it’s a lot harder than she thought it was going to be, that romantic love is not answering a lot of the questions that she wanted. And I don’t think Jesse had any of those expectations that romance was gonna answer for him so he’s a lot happier. I think he’s clearly invested in that relationship and he’s clearly invested in loving that woman. Her problems are stronger and I think more developmental. I see this – like I said, with a lot of women I know – so I relate to it and I don’t see it without a lot of hope.

That makes me happy.

That’s how I really feel. There’s something about the last line in that movie about us all being in a space time continuum, and theres a play on misquoting time – I forget the exact line – but it’s like: “That’s the best night I never had.” We all want to get to this end where we’re on this plateau where everything’s happening but the truth is we’re caught while we have the gift of being alive. We’re caught in this constant play of things going well and then they go badly and then they go well again and what we thought was bad ended up being good – and what we thought was good ended up being bad. Life is so much more mysterious.

Something that fascinates me about those films is the writing process – you and Julie both have screenwriting credits on Sunset and Midnight and I’m really interested to know what the process was.

I find it endlessly fascinating because each one happened differently. The first one, Rick had this idea for a movie, and he and this woman, Kim Krizan, they worked on an idea of a script. I read it – it was a very strange script [laughs], really weird. It had a page and a half monologue of Jesse talking about John Huston’s The Dead (1987). I was like, “Listen, Rick, nobody but you wants to hear a thesis on that film in a movie.” He was like, “It’s just a placeholder, I want them to share his passion for art.”

But really what it was was that Rick came to Julie and I with this construction – I remember this is what he said to me: “I want to make a movie about where the only thing that happens is the greatest thing that’s ever happened to me which is connecting with a human being. I’m challenging myself to make a movie about this connection so I need you guys to connect – you gotta help me make this movie.”

This was his dream: they were going to meet on a train, he was gonna talk her into coming off, they were gonna kiss on the same ferris wheel that The Third Man was shot on – he had these bullet points where he knew what was going to happen, he knew what the ending of the movie was going to be, but colouring it all in he wanted Julie and I to do. He’s actually very moving when talking about this because one of the things he was reeling from a little bit when I met him was his inability in his own mind to make the female characters as dynamic as the male characters in Dazed and Confused. He didn’t feel like he succeeded in realising them. The movie has a very male gaze and it wasn’t his goal. I mean the movie’s great – it’s one of my favourite films of all time – but it is a boys’ movie. So he was really coming to Julie and saying, “Look, what do you want her to be named? I want you to contribute. Who is she? Tell me about her? Let’s create her together.” And he said the same thing to me.

So that was the first movie and we walked away from it and said goodbye to those characters. I didn’t think anything was going to happen with it until Rick was making Waking Life (2001) – this whole movie about dreams – and he wanted Julie and I to write another scene with him. He said, “Hey, let’s get together, I want Jesse and Celine to appear in this dream movie.” We had so much fun writing that scene that we walked away and were like, “We’ve got to work together again.” It’s too unique – the energy between the three of us is very strange, it felt like putting your finger in an electrical socket and [finding] there’s energy still there.

So then we started thinking, what would that next movie be? We struggled with it for a couple of years. I was then doing a book signing – Linklater came out – and there it was. Like, “This is how the second movie starts: Jesse’s written a book about his night with Celine and she should show up at a book signing.” It was like [clicks]. He went, “I don’t know what happens after that,” and I was like, “Nothing! That’s it! That’s the whole movie!” We literally got in Rick’s pickup truck and we were driving out somewhere and we called Julie, and so that one started where the three of us conceived of it as a whole.

The third one was stranger than that – we kind of agreed on what it would be but we didn’t have very much written. The third one we really wrote together in a room. That was a battle. That was a battle.

Do you reckon there’ll be another Before film?

I don’t know. I would have said after the second there was definitely going to be a third one, but I do feel complete, in that the first one starts with the older couple arguing on the train and by the end of the third one we’ve become that couple. If it were to continue, it would change shape. It would be something else. Julie, Rick and I might work together again, we might revisit those characters, but it’ll need a new burst of energy. I don’t know what it is. We’re not allowed to think about it until five years after – that’s how we’ve done it every time. Waking Life was five years after Before Sunrise. And Before Midnight, we met five years after Before Sunset. So we’re gonna meet five years after the release of Before Midnight, talk about it and see where we wind up.

Linklater told us that you’re both planning on adapting King Lear as the last thing that you ever do. Is that still the plan?

We’re preparing for it. He’s got to do his homework to know what he’s going to offer that material, but it gives us an end game.

You’ve directed your first film, Blaze. What’s the story behind that project?

I’ve been directing a bunch of theatre and having a really great experience, and I was really hypnotised by the story of Blaze Foley and wanted to make a gonzo indie movie like the ones I’d heard and read about. We went down to New Orleans with about five bucks and a camera and came out with a pretty amazing movie about this musician who was shot and killed in 1989. I’ll hopefully be finished with that in around November – I’m editing and doing the sound design now – so it’ll probably premiere in the Sundance, South by Southwest, Berlin festival period. It was definitely one of the most exciting... [trails] I poured everything I learned into that. I think you’ll like it. Rick is in it, you know. He’s playing a record executive.

Maudie is in cinemas now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments