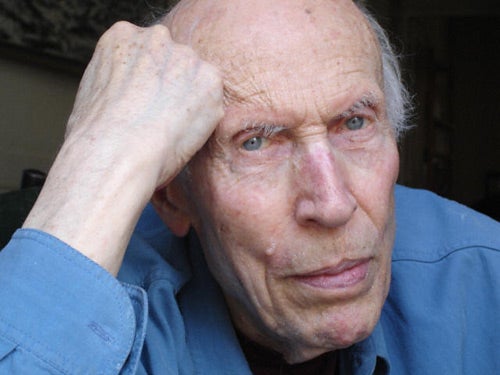

Eric Rohmer - father of the New Wave

Eric Rohmer is a writer who became a pioneer of modern French cinema. He tells Kaleem Aftab his latest may be his last

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Eric Rohmer has always been the most discreet of film directors. While his contemporaries saunter from film festival to film festival and spend hours in interviews spouting their views on film and life, Rohmer has, by and large, chosen to stay at home. The first inclination of his cloaked nature came in 1946 when he chose to release his novel Elizabeth under the pseudonym Gilbert Cordier. Even Eric Rohmer is an alias: he was born Jean-Marie Maurice Scherer in 1920.

He came up with his auteur signature (fashioned together in homage to the actor and director Erich von Stroheim and the 19th-century English novelist Sax Rohmer) because, he claims, his society family were embarrassed that one of their own would choose cinema as their living.

Whether it's true or not, the story fits in perfectly with Rohmer's aim when starting out as a film critic in post-war France, that cinema should be recognised as "the Seventh Art", as valuable an artistic pursuit as painting and books. The classicism that Rohmer saw in film is clearly evident in his latest work, The Romance of Astrea and Celadon, which is inspired by the 17th-century novel Astrée by Honoré d'Urfé.

Knocking on the door of Rohmer's office in a Paris apartment building, I hardly know what to expect, having been granted the interview on the proviso that it could be cancelled if the film-maker's ill health demanded. I need not have worried. Despite being gaunt and having skeletal features, he is in good health. Sporting a cravat and a blue pullover, he looks the archetypal French artist. He ushers me into his main office-space. The detritus of more than six decades of work seems to be dispersed everywhere. Folders, books, papers and journals are crammed on every surface, except the chairs where we station ourselves either side of his small wooden desk, positioned far from the window of the oblong room.

As I look across at him, I suddenly have a sense of what it must have been like for the young Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut, going to Rohmer cap-in-hand in search of a few pennies. A former literature professor, he was the oldest of the film critics who penned articles for Cahiers Du Cinéma before going on to direct the films under the banner of the New Wave. Of that group of directors who changed the face of cinema, it is Rohmer who has remained closest to their philosophical roots.

"Well, it's not the nouvelle vague [New Wave] any more, we're all old now," he jokes. "Obviously Truffaut has died, but both Claude Chabrol and Jacques Rivette have made films recently, and Godard, I understand he is the process of preparing to make a film. If we have the same cinema, or if we have evolved, it's not up to me to say.

"It's true that Godard has probably grown more as a film-maker but away from the public, while Chabrol has become a more commercial film-maker. I think we are all loyal, more or less to the same principles that we have had at the time.

"Myself, I keep the same idea of cinema and at the same time I always do films in my own little way: films that are not too expensive. I like shooting, even when I'm in a studio, I like shooting nature, and I give an importance to the poetry of cinematography. It's very much still following the theories that I expounded in my early articles."

Detractors of the auteur, of which there are many, would argue that Rohmer tells the same story in the same style over and over again. There is little in the way of plot and it's hard to decipher the motivations of the protagonists.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Rohmer defends the similarities in his pictures. "It is better to see all my films together as a collection. At the moment they're showing the Four Seasons on French television, one part each week, and that is perfect. There is a relationship between all the films and that is where the interest lies.

"Whether you think that my films are good or bad, they have a value to one another that helps with understanding them. The public often tell me that I make films that resemble each other and they are right, but it is normal because I am a complete auteur, that is someone who creates the film, looks at the subject and at the same time I am also the man who creates the image."

The Romance of Astrea and Celadon is set in fifth-century France in a world of nymphs and druids. A shepherd, Celadon, tries to win back the heart of Astrea, who falsely believes that Celadon has been unfaithful. Along the way Celadon resists the temptation of a beautiful nymph.

Rohmer says of his adaptation: "The book had a lot of success in the 17th century. It's one of the first written in a French language that a modern audience can understand. It has a dialogue that is very clear and good and relevant to today. Modern audiences will recognise the characters but not straight away... this is normally why my films don't have a big public and cater more for a certain literary audience.

"You can take an English novel from the 19th century and they essay many of the situations that I address. I've read a lot of authors of the 19th century – Joseph Conrad, Robert Louis Stevenson, Henry James – and these authors have marked me a lot."

At the outset of the film, in a droll intertitle, he makes a playful comment on the fact that the shooting took place in a location far from where the events are depicted in the novel, because idyllic countryside has been replaced by concrete jungles. The director has never owned a car, and rarely takes taxis, although he does point out that this is more to do with the type of films he makes than an attempt to improve on his already impressive green credentials: "I do this to be in touch with everyday life. If you are hidden away in a taxi you're not in contact with reality, and in my films I try to show people in real situations, especially in my films in a contemporary setting. I can't do this if I stay in big hotels and hide from the public. It's why I don't show my face often in the media. People don't recognise me, so I can get on public transport. It also helps when I'm making a film, I can work on location and people don't recognise me or the actors and it allows me to shoot."

The method of shooting with a small crew and using the latest equipment is typical of the 87-year-old. "I've always been interested in new technology," he asserts. "The first article I ever wrote, even before Cahiers, was for a journal called Revue du Cinéma. In was on the use of colour over black and white. It was at a time when people preferred black and white, but I liked colour and also the use of direct-sync sound."

Sad as it is to report, he intimates that The Romance of Astrea and Celadon is likely to be his swansong: "I haven't got plans to make another film, it's not easy for me to make films now. These days it takes me much longer to prepare a film then when I was younger."

If this is his last film, it will bring the curtain down on one of the great classical artists of the last half-century.

'The Romance of Astrea and Celadon' is out later this year

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments