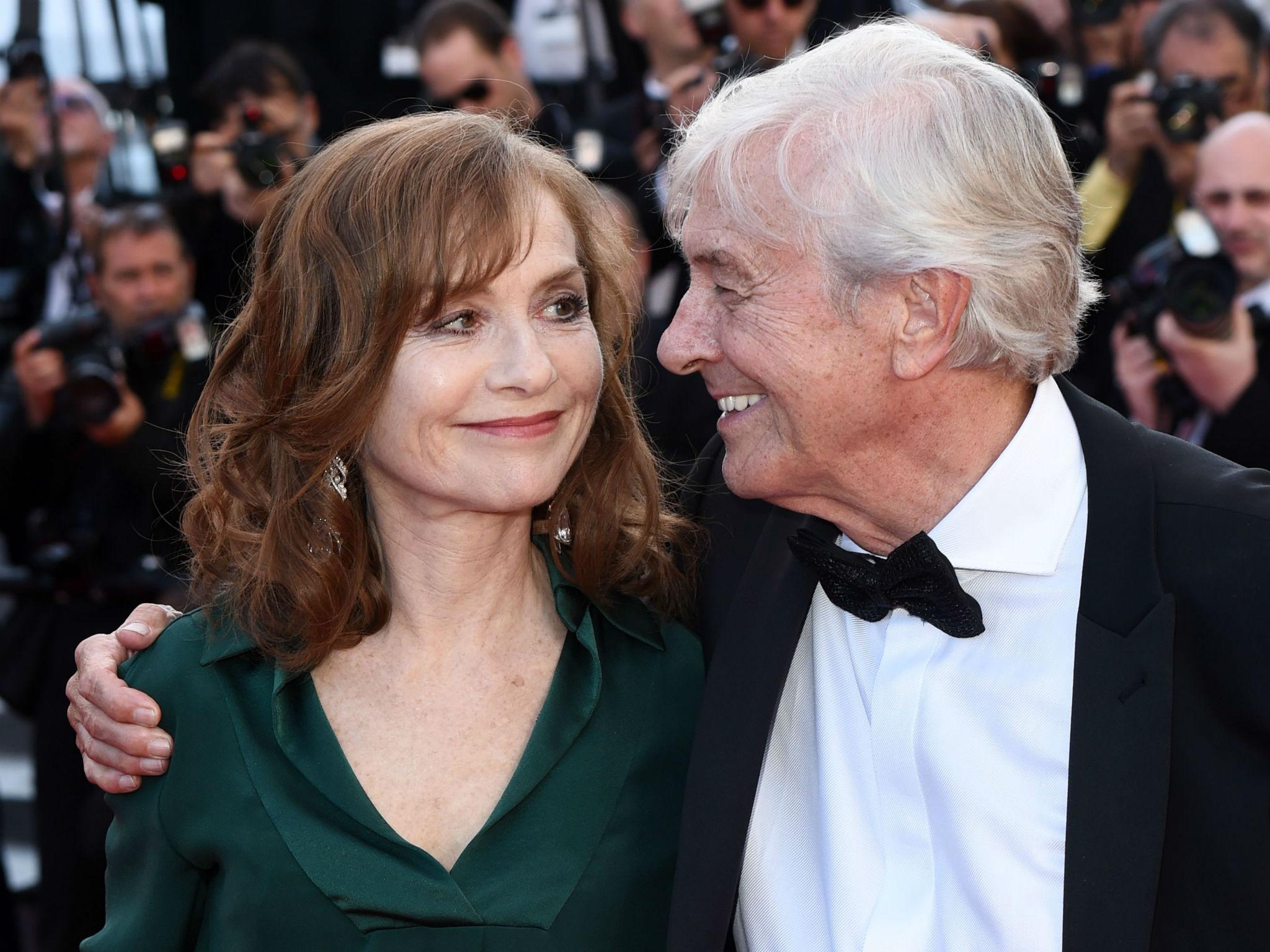

Elle's Oscar nominated Isabelle Huppert: 'The camera is really like an X-ray of your thoughts'

The film's director Paul Verhoeven and the French actress, who was Oscar nominated for Best Actress in 'Elle', talk about the film in which a rape victim tracks down her attacker for sadomasochistic thrills

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

Elle sees Basic Instinct’s notorious Paul Verhoeven direct France’s icon of icy transgression, Isabelle Huppert, in what sounds like their ultimate provocation. This is a film in which Huppert’s Michéle not only seems unbothered by her rape in her Paris apartment at its start, but later seeks out her rapist for sadomasochistic mind-games and orgasmic sex.

The always conservative Oscars blanched at Elle as Hollywood stars from Nicole Kidman to Julianne Moore did when Verhoeven sought them to audition for Michéle. But the Best Actress nominations couldn’t ignore Huppert’s wholly original portrayal. Publicly associated with the crimes of her serial killer father when she was ten, this overdose of shame maybe makes Michéle immune to it. All we know is that she doesn’t care what anyone thinks. Even as she’s raped, she defines herself.

When I meet Huppert in her London hotel room, she seems physically small and anonymous, her formidable on-screen potency switched off. The ironic intelligence she shares with Verhoeven remains alert, though. Whether as the syphilitic, matricidal antiheroine of Bertrand Blier’s Violette Noziere (1978), or masochistic and violent in Michael Haneke’s The Piano Teacher (2001), her award-winning roles have repulsed Hollywood. As she once said, “I like exploring monstrous instincts.” So is Michéle one of Elle’s monsters?

“No. No, no,” Huppert says, surprised. “I don’t see her or act her as a monster. The only thing that makes her a bit apart from my world, at least, is that she’s not afraid. And that’s not so common. That’s really far from me. I’m afraid of everything, and, especially after what happened to her, I would never live alone in that big house in the suburbs of Paris. Never! That’s the most male side of her – I’m afraid I have to say,” she laughs wryly. “Because a man, in general, is less scared to be alone in a big house than a woman.”

Huppert is careful to separate her private life – where she has been married for 35 years to the film-maker Ronald Chammah, raising three children and occasionally leafing through philosophy books, a little like her professor in last year’s Things To Come – and her risky art. She only shares Michele’s dangerous freedoms up to a point.

“As an actress yes, for sure,” she says. “But frankly, I really don’t feel I’m taking any risks. I just do great roles in great films. I must be naïve or whatever, because I don’t see the problem with that.”

“Shame isn’t enough to stop us doing anything at all,” Michéle says, a bit after she’s rung her rapist to pick her up after a car-crash. In Elle’s wild, freeing fantasy, she simply doesn’t have the shame which makes rape worse. Instead of a perversion, her actions feel like a victory. “Oui, oui, a victory... She’s not a victim, she doesn’t want to be a victim,” Huppert says. “But what I like about her is that on the other hand she’s also not the caricature of the revenge girl, taking the gun and shooting the guy. It’s a bit like psychoanalysis, where the unconscious drives you more than anything else. It’s really a psychoanalytical film, I think. You are being pushed by a thing that you don’t even know.”

Huppert gives Elle subtle grace notes. Though most reviews claim Michéle blithely picks herself up after her rape, still bleeding, and gets on with her day, she tidies up clumsily. There’s shock beneath her sangfroid.

“She must be in shock, yes,” Huppert agrees. “Who wouldn’t be? But she has her own way to come to terms with that. By first of all putting all the pieces back together, sweeping with the broom, and then ordering sushi. I don’t really have explanations for that. I certainly wouldn’t react the same way. Eventually as we step more into this woman’s life, we understand that she was confronted with violence by her father when she was a little girl, she has a crazy mother. She has so many things to control. The whole movie is about the fact that there is no really satisfying explanation. But she shares a quest for love, maybe. I think what’s really touching in the film is that [in the rape’s aftermath] she wants to create a connection with her father’s violence. The film says a lot about family ties.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

The rape itself is only heard, at first, then briefly recalled later. Verhoeven, who was driven out of his native Netherlands after scenes including a gay gang-rape in Spetters (1983) and included female rape in the infamous Showgirls (1995), was untypically careful to avoid exploitation.

“The balance and subtlety of the script,” he tells me, “and of Isabelle Huppert to hold that together, means we didn’t fall into that trap. I kept it extremely short, to avoid facing any thought of sexuality in the rape. I felt it needed a subtle approach. There were probably other movies when I was younger when I didn’t feel it so necessary to be nuanced – let’s put it that way.”

From the more rigid, no-platforming end of feminism to permanently outraged right-wing newspapers and most of the social media in between, our official morality seems desperate to limit our permitted reactions to life, and sex especially. As Michele experiences what Verhoeven calls “a very powerful orgasm” in later, consensually violent, sex with her rapist, Elle takes us on a trip past these absolute edicts. As in all Verhoeven and Huppert’s liberating work, characters are free to behave as they want.

“Absolutely,” Verhoeven agrees. “This movie is outside the discourse about rape, especially in the United States. We’re not even thinking about that. This woman happened to be this way, and she finds her own solutions, and she doesn’t even want to hear about compassion. She is able to integrate [the rape] in her own life, and work with it, and work against it, and perhaps find out about what happened. But she doesn’t need anybody else. It’s her own justice. You’re talking about a very specific character, and not rape in general.”

There is an anarchy to Verhoeven, in bridge-burning films such as Spetters and Showgirls, which was born in his childhood under Nazi occupation in The Hague. He knows the world is chaotic, and you just have to let people get on with surviving it.

“Yeah,” he agrees. “And you can change it a little bit here and there, but in the next generation or two it becomes chaotic again. You can see that clearly in politics today. After witnessing the war in The Hague, and seeing all the destruction and the dead people, there was a feeling after 1945 that there was stability, at least in Western Europe. And now it feels like we’re going back into the kind of chaos that must have reigned in the 1930s.”

Verhoeven’s Turkish Delight (1973) was one of Huppert’s inspirations as an actress, and they didn’t need to discuss her performance in Elle. She understood what to do. “What I like most about Paul is his huge irony,” she says happily, “and the flick between that and the film’s emotion. For me this movie is quite touching. Because it’s a quest for love, it’s a quest for life. But I like how Paul keeps a distance so you go away from any sentimentality, any psychology, and stupid explanations.”

Elle is also, unexpectedly, a comedy. “Yeah, sure,” Huppert says. “It’s not only a comedy, but it’s very funny, because the situations were funny, and the little details. You know, like the man at the Christmas meal, when he right away put his hand on my hand – ooh, my God! Michele has exactly the reaction I would have personally, to many, many situations. Instead of being serious, instead of doing [dismayed gasp], ‘Oh…’, she goes [with amused surprise], ‘Oh!’ It’s very nuanced, the irony, but it’s very important.”

The prolific Huppert had another film at last year’s London Film Festival, where we met. In the much lighter Souvenir, she plays a former Eurovision one-hit wonder, dragged out of whisky-fogged retirement by the love of a smitten young boxer. Huppert’s performance shares one quality with Elle which is particular to her. The camera silently observes her as an intelligent, self-sufficient woman, busy thinking her own thoughts.

“That’s the best compliment you can tell me,” she laughs. “But maybe this is something I provoke. It’s like the scorpion, I don’t know how to do otherwise. It’s certainly something I did in Things To Come, and Elle, and Souvenir. Certain roles don’t provoke that as much, but when they do, it’s very organic with me. Because it’s also what the camera allows you to do. The camera is really like an X-ray of your thoughts, and you have to use that as much as you can. It’s really pleasurable.”

Is she thinking the character’s thoughts?

“You have so many layers of thinking when you act,” she considers, “it’s very strange – you think what you act, you think what the character thinks. You don’t think at all, in a way. So it’s a very complex substance of thinking when you act, I would say, because it’s between something completely unconscious, and something super-conscious. It’s almost like when you are drunk, or a little bit drugged. It’s a super-awareness of the world.”

For all her wry dialogue in films like Elle, in some of her best work, Huppert says nothing. So often stone-faced where other actresses are compelled to charm, she could be the last silent movie star. “If you always talk, and take,” she says, “sometimes in movies, everything’s always full. It’s nice to have a bit of emptiness.”

There is one other way in which and Huppert’s triumphant, iconoclastic new film denies Hollywood convention. She is 63, and Verhoeven 78, but both are at their peak.

“It’s to keep other things that are much less pleasant, like the end of life, at bay,” Verhoeven explains of his continuing conviction. “I feel that if I did not work, then dark thoughts would invade my brain. And I’m still naturally curious. And in fact, by having to learn French and going to France where I knew almost no one to make Elle, there was fear, but all of the talents that you have are activated to get through it. Fear is creatively excellent. It’s about living in the moment, and standing at the door that you open, and not knowing where it will lead.”

Elle is in cinemas from 10 March

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments