Edinburgh Film Festival: Inside the Art house

Two films about the art world will be among the highlights of the Edinburgh Film Festival. The directors tell James Mottram why the time is right for their insider portraits of creative hotbeds

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Filmmaking is ponderous by its very nature. The process of screenwriting, development, funding, shooting and editing can take years. So to make anything that feels vaguely topical, you need to either position a crystal ball next to your camera or be extremely lucky. But, arriving a week after Banksy staged his own audacious exhibition in Bristol's City Museum and Art Gallery, two films due to be unveiled at the Edinburgh International Film Festival in the next few days suddenly feel remarkably timely.

Duncan Ward's Boogie Woogie and Alexis Dos Santos' Unmade Beds both cast their eye over Britain's current art scene, albeit from very different perspectives. Boogie Woogie is an all-star ensemble (featuring Danny Huston, Gillian Anderson, Heather Graham, Alan Cumming, Gemma Atkinson and Joanna Lumley, among others) in which dealers, artists, collectors and wannabes all prowl around each other in the desperate hope of either discovering or being discovered. Based on the book of the same name by Danny Moynihan, Ward's film is a comedy of manners, giving an insight into the hungry agendas of some of the international art world's major players.

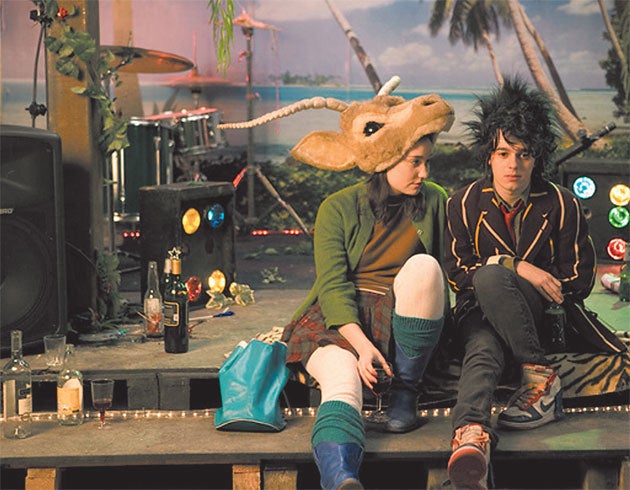

Meanwhile, Dos Santos' film is at the opposite end of the spectrum: two foreigners living in an East London squat find themselves sucked into a vibrant world of struggling artists and musicians. This is the second feature film from the Argentinean director, whose feature debut, the 2006 film Glue, explored dysfunctional teenagers as they struggled with adolescence. His follow-up charts the journey of two young, wayward expats (played by Déborah François and Fernando Tielve) in a dreamlike fashion, set to a soundtrack that features cameos by contemporary UK bands. Against the backdrop of a buzzing London, the pair find themselves in a creative hotbed.

As far as Ward is concerned, it's the media's recent and ever-growing obsession with the art world that has made this possible. "Only in the last five to 10 years has art made front-page news as regularly as it has done. Artists such as Damien Hirst are making their own auctions, manipulating the market with the same sort of tenacity as dealers previously used to – and still do. The public perception of art and awareness of it is much greater now. Beforehand, it was always – right up until the late Nineties – still very much a specialist environment that few people knew of: bar collectors, dealers, artists and interested people."

A documentary film-maker by trade, Ward has made films about artists such as Tadeusz Kantor and Leon Tarasewicz. He also worked with Brian Eno on the 1989 film Imaginary Landscapes. "It's never been something that I've not been in," he says of the art world. His wife, Mollie Dent-Brocklehurst – who used to work for the renowned dealer Larry Gagosian – now runs the Moscow-based gallery the Garage and buys art for a certain Roman Abramovich. Contacts such as these enabled Ward to secure his actors access to this rarefied universe during the course of their research.

With the story being based on the novel by Moynihan – another art-world insider, who has worked as an artist, curator and gallery manager in London and New York – Boogie Woogie immediately brings to mind the rise of Hirst and other members of the Young British Artists. Jaime Winstone's character, for example, is Elaine, a lesbian video artist whose provocative work has a whiff of Tracey Emin about it. Ward is too diplomatic, however, to confirm whether or not she was the main inspiration. "Everyone in the art world will know that character inside out," he says. "They've witnessed that artist several times over."

Indeed, while film-makers have made films about real-life artists before – Julian Schnabel's Basquiat, Ed Harris' Pollock and Robert Altman's Vincent & Theo, to name but three – rarely has a film attempted to capture the ins and outs of the art world itself. "Boogie Woogie is the first of its sort," claims Ward. "The other movie that could be closest to it is [Altman's] The Player, which dealt with how the film industry operated. That was very cogent about how it moved, and we've tried to do something not too dissimilar. So you see the high and the low players all mingling."

Still, Ward stresses he didn't want to make a "how-to" that sets out to lay the mechanics of the art world bare. He's also careful to underline that the film is not a cynical exploration of the industry. Indeed, given that he and Moynihan are good friends with Hirst, Boogie Woogie feels like it has an official stamp of approval. One scene even revolves around an exhibition of Hirst's work (featuring reproductions of many of his efforts, including his "biopsy paintings"), while the artist is said to have helped select some of the other art-works – including pieces by Banksy and Emin – that feature in the film.

While Boogie Woogie sets out to gently satirise the art scene, Unmade Beds comes from a more heartfelt place. If the title recalls Tracey Emin's controversial work My Bed, that's as far as the comparisons go. Set in a bohemian community far removed from the glossy world of Boogie Woogie, Unmade Beds shows a side to London's cultural scene that has rarely been put on film. "Most British films, they're usually either social realism or the opposite – like the Richard Curtis romantic comedies," says Dos Santos. "I hadn't seen many films that were set in this youthful environment that you actually see in London a lot."

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Running two parallel stories – a Spanish slacker, Axl (Tielve), is looking for his father while a French girl, Vera (François), is embarking on a new relationship – the film puts its characters in a student-like setting that Dos Santos knew from personal experience. Having lived in London for 10 years, he used to frequent a squat in the Elephant and Castle that resembles the industrial-sized space where both Axl and Vera crash. "It was four floors of a massive warehouse. People living there were young artists, art students, musicians, kids that were doing art stuff, and they were throwing parties there all the time."

With the film eschewing the more trendy Hoxton for Dalston and London Fields, where impoverished art students are 10 a penny, Dos Santos believes London is a hive right now for emerging artists and musicians. "You have so many bands starting. You can go to bars where they have bands playing every night, and they'll be amazing gigs. And they're all starting or they've been there for a couple of years, and they're really good. And you've got something similar happening in art. For art, London is one of the most important places in the world. It's where everybody goes – so many great artists started in St Martins or Goldsmiths."

Unlike the Hirst-supported Boogie Woogie, Unmade Beds is populated with more underground talents. Bands such as (We Are) Performance, Connan Mockasin and Plaster of Paris all make an appearance in the bars and clubs frequented by the characters, while art-work from the Derby-based artists Ali Powers and Alex Giles also appears in the squat. If anything, the film suggests that London's really "happening" art scene is not to be found in high-end galleries, but can be glimpsed all around us. Take, for example, Vera's habit of photographing unmade beds. "She is the one in the film who will become an artist," notes Dos Santos.

If anything links the two films, it's the sense that artists remain perennially fascinating figures for those of us who live a more traditional existence. "A lot of artists in the past have lived art," says Ward, "which is what a lot of people can't do because they're restricted by the forms of their employment. It's very free and bohemian."

What's more, art, whether it's urban graffiti or displayed in the Tate, still continues to intrigue, outrage, provoke and enchant. "Our lives are designed around it in one way or another," reckons Ward. "Everything is informed by some kind of artistic decision – even the logos on the back of your jacket."

Although film-makers may only just be turning their attention to the art world, artists have been making the crossover to film for some time. Aside from Schnabel, British artists who have found their way into the film industry include Steve McQueen, who made the Bobby Sands drama Hunger; Douglas Gordon, who made the sports documentary Zidane: a 21st-Century Portrait; and Jeremy Deller, who co-directed the Depeche Mode fan documentary The Posters Came from the Walls. Currently, Sam Taylor-Wood is putting the finishing touches to her first feature film, Nowhere Boy, a biopic of John Lennon, having already directed the "Death Valley" segment of the erotic portmanteau movie Destricted.

While this might suggest that artists are all too ready to hop into bed with film producers, whether it be to reach a wider audience or explore something on a different canvas, Ward thinks they're not as connected as you might expect. "You imagine they'd be informed by one another. But they're two very distinct and different industries. The film world is much more governed. It's far less laissez-faire than you think, as you have much bigger budgets and the enterprise is much more corporate. Whereas in the art world, anybody can become a dealer or an artist. It's the most democratic bastion of activity you can find. For all of that, it should be ramped up and encouraged."

Admittedly, it's hard to imagine the film industry ever being run like the art world or accommodating a maverick talent such as Banksy. "The irony is obviously that film craft is so much more disciplined than video art," says Ward, who believes the latter is "the curse of the last decade" because most artists will opt for it as a means of expression rather than learn more traditional skills like draughtsmanship.

"It's a shorthand for a lot of things that people aren't able to do," he adds, noting that anyone can pick up a video camera. "It's a question of what it is that you make that makes the difference." Perhaps artists can learn from film-makers yet.

'Boogie Woogie' screens at the Edinburgh International Film Festival on 26 and 27 June; 'Unmade Beds' screens on 24 and 26 June. Both films will be on general release later in the year

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments