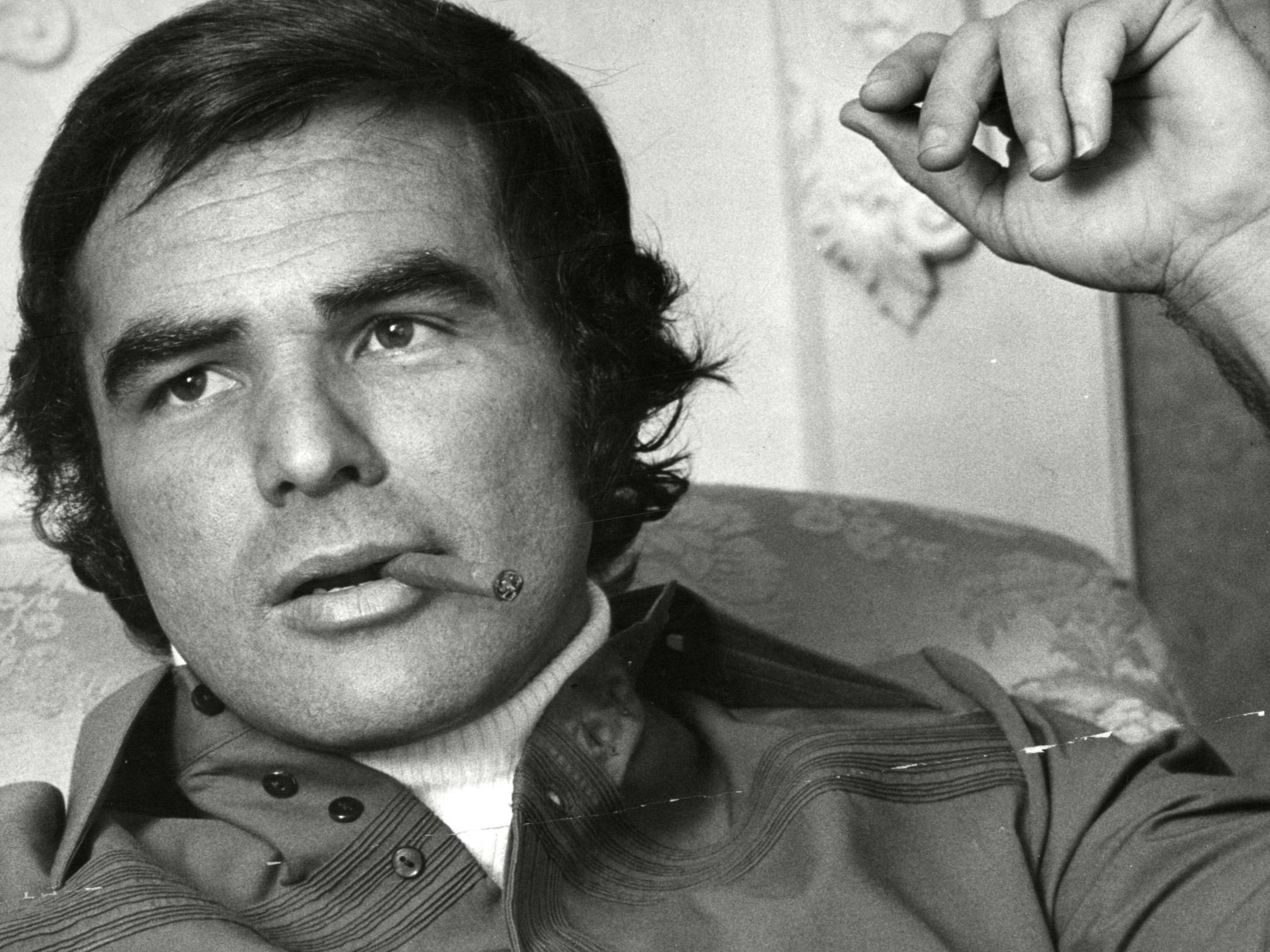

Burt Reynolds tribute: The closest the modern era came to producing its own Clark Gable

The carefree Adonis' greatest quality was that he always looked as if he didn’t give a damn

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Burt Reynolds’s appeal as a movie star lay in his rugged dependability and in an unlikely self-deprecating charm. He was a very macho figure but one with a twinkle in his eye, as close as the modern era has come to producing its own Clark Gable. (Like Gable, he was generally seen on screen with one of Hollywood’s most instantly recognisable moustaches.) He could seem boorish one moment and gallant the next. He could seem very narcissistic but then make a joke about his own thinning hair. He could appear mean and intimidating but would then leaven the mood with a quip or with that sly smile. Like so many of the best screen actors, he knew that less was more. There was no extravagance when he was in front of the cameras.

Many of his most famous performances were in action movies that had their tongue firmly in their cheek. He excelled in romps like Smokey And The Bandit and The Cannonball Run. He had a flair for comic understatement on screen and off. “My movies were the kind they show in prisons and airplanes, because nobody can leave,” he once said of himself.

At the same time, Reynolds was at home in much darker, more challenging material - in John Boorman’s bloodcurdling outdoors tale, Deliverance, or in a hardboiled modern-day film noir, Hustle. He also took his own status very seriously and didn’t like it all when he felt slighted or underpaid.

Reynolds’s peak years, the 1970s and 1980s, were a period of turbulence and doubt, both in Hollywood, as box office receipts dwindled, and in American society as a whole, post-Watergate and the Vietnam War. One reason audiences so cherished him was that he rarely showed doubt or anxiety. He was the opposite of the neurotic, inward-looking method actors of his era. He was also one of the few big names who was equally at home in prestigious old-fashioned Hollywood A-features, in the video-driven B movies that began to be made in such profusion, or on TV. He had no snobbery about which medium he appeared in.

Late in his career, when he stopped playing leading men, Reynolds was rediscovered by a new generation of independent filmmakers. He received more awards nominations in supporting roles in films like Robert Altman’s The Player or Paul Thomas Anderson’s Boogie Nights than in the years when he was one of the industry’s best-paid leading men. Some directors found him nightmarish to work with but many others found that he had hidden depths and skills.

Reynolds may have been a brilliant screen actor but he was a lousy businessman with a messy private life. The carefree Adonis of the Seventies (one of the first male nude centrefolds) eventually turned into a shambolic figure, caught up in legal cases and running short of money, late in his life. He wasn’t always astute in his career choices either. Some of his less happy and distinguished film experiences were in British-made movies, for example in Mike Figgis’s Hotel, shot in Venice, or on A Bunch of Amateurs, a comedy shot in the unlikely settings of the Isle of Man that was said to have lost a small fortune. Britain was also the source of one of his biggest regrets. He was in the running once to play James Bond but turned the role down. Rejecting plum parts became an occupational hazard for him as his career began its long decline.

It’s easy to sneer at Reynolds for appearing in too many testosterone-driven movies aimed at an unreconstructed male audience. You didn’t find him playing too many sensitive types or taking roles in romcoms (although he was offered the Richard Gere part in Pretty Woman.) Nonetheless, there was a time when he was a ubiquitous and much-loved presence on British film and TV screens. You knew exactly what you would get from a Reynolds movie - swagger, action and some very dry humour. He was an old-fashioned star whose greatest quality of all was that he always looked as if he didn’t give a damn.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments