The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

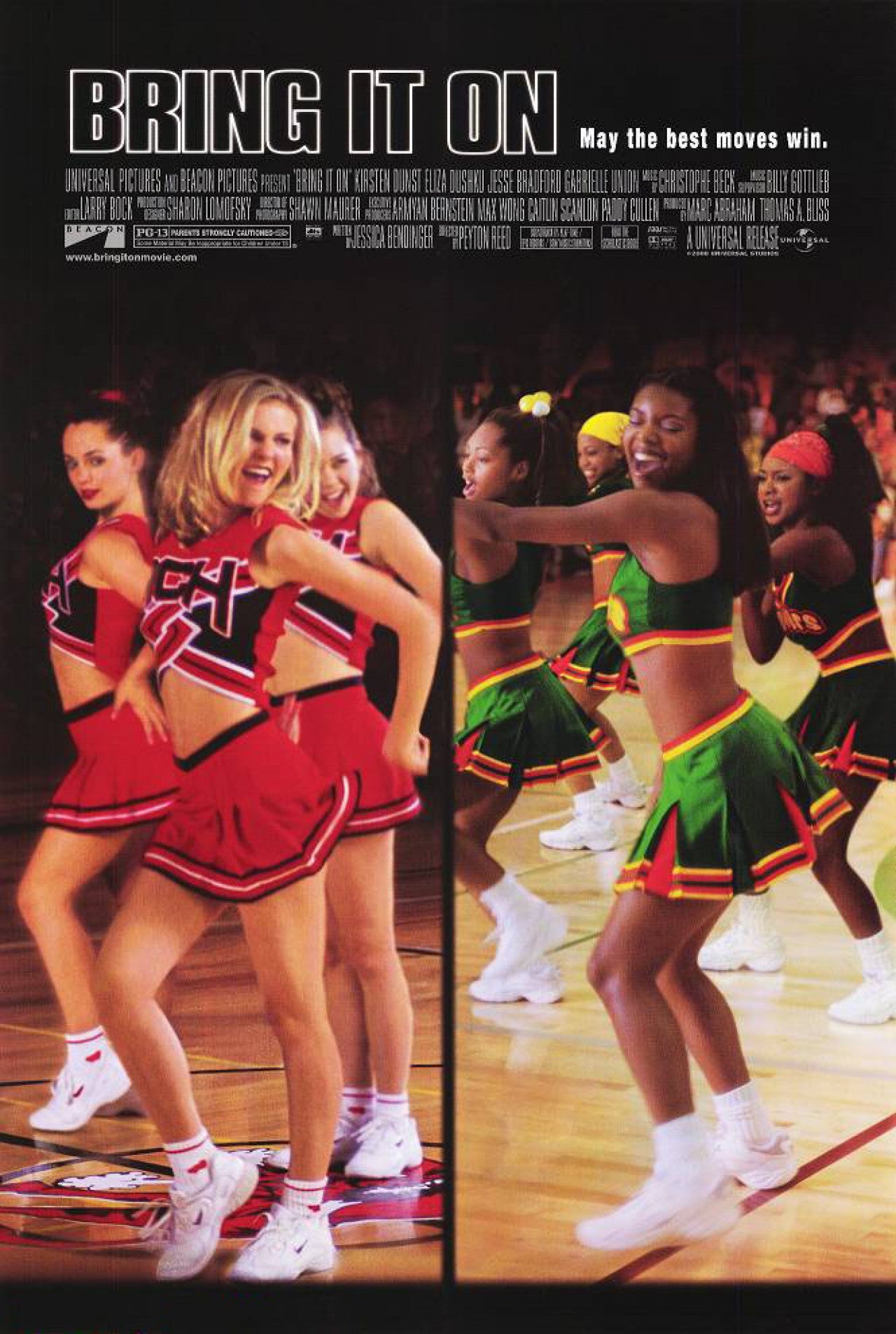

‘I’m sexy, I’m cute, I’m popular to boot’: Bring It On took aim at white privilege, one pom pom at a time

Though it was initially written off as a soapy cheerleading romp, 20 years on, the film’s themes of black oppression and appropriation ring even more true today, says Adam White

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Bring It On is a glittery bath bomb of a movie, awash with spirit fingers and aerial stunts. Twenty years after its release on 25 August 2000, it remains a classic of that era’s teen cinema boom, which was kick-started by Clueless in 1995 and petered out once Freddie Prinze Jr’s hairline began to recede. The film’s surface charms remain much the same after two decades, with only a few too-casual homophobic slurs to make you bristle. That aside, however, its major themes have only deepened. Smuggled in beneath the pom poms, the result is a film far more politically and socially resonant than likely remembered.

Kirsten Dunst, in the midst of an enviable run of films that included The Virgin Suicides (1999), Drop Dead Gorgeous (1999), Dick (1999) and Spider-Man (2002), plays rich LA cheerleader Torrance Shipman, who is determined to carry her team to victory at a national championship. There are feuds, love interests and a snarky tomboy newcomer in the form of Eliza Dushku’s Missy to deal with, but all pale in comparison to her biggest problem: the routines handed down to her team from the previous year’s head cheerleader were actually stolen from a troupe of black, working-class cheerleaders led by Gabrielle Union’s Isis.

Today, Bring It On has only grown in popularity since its release. It also spawned five (five!) straight-to-video sequels, one of which featured a ludicrously overqualified cast that included Solange, Rihanna and Hayden Panettiere. But at the time, in 2000, its recognition had to be fought for. Upon release, the film drew mixed reviews. Roger Ebert called it “juvenile and insipid” and Variety argued that director Peyton Reed struggled to align “jarring” shifts in comic tone from the sweet to the broad. Only a handful of critics seemed to recognise the film’s political slant: look closer and the film, said The New York Times, had an “unapologetically feminist heart” and took on “serious matters of race and economic inequality”.

Bring It On, ultimately, is about white ignorance in the face of black oppression. Torrance and her squad didn’t for one second suspect that their primary cheer, complete with rap and music courtesy of DJ Kool and rapper Biz Markie, may have been written by black cheerleaders rather than a privileged white one. “I know you didn’t think a white girl made that s*** up,” remarks Isis at one point. The dialogue that follows succinctly explains cultural appropriation, with white people snatching at elements of black culture, often diluting them, and then passing them off as their own. “Every time we get some, here y’all come trying to steal it,” Isis says. “Putting blonde hair on it and calling it something different.”

Jessica Bendinger’s script is also interested in what tends to happen when white people are alerted to their own privilege. Many of the Toros, the name of Torrance’s squad, are at first ambivalent to the cheating, arguing that Isis and her fellow Clovers have no proof of the theft, so why bother acknowledging it?

Torrance is more outwardly empathetic, but she attempts to quell her own guilt by literally paying her way out of, coaxing her wealthy father into writing a cheque for the Clovers so they can afford to travel to the national championship. She intends it to be a peace offering. Isis scoffs at it. “You pay our way in and you sleep better at night,” she says. She then rips up the cheque, insisting that the Clovers only want the Toros to “bring it” at nationals, not offer “guilt money”. It’s an early refusal to make Bring It On the story of a white person improving themselves, or a film where black characters exist as mere tools in their political awakening.

Bring It On isn’t subtle about what it’s eager to explore. There are no token white Clovers or black cheerleaders on the Toros to dilute the racial disparities between both teams. Union appeared to be an important influence on set, recognising the weight of the film’s themes and refusing to say absurdist dialogue she described in 2015 as verging on “blaxploitation”. What results is a story of strong and ambitious black women fighting for a spot on a platform dominated by white people, who only got there, and maintained that subsequent power, through illicit means.

It’s most striking as a theme because this was Union’s third ride on the teen movie rodeo. In both She’s All That (1999) and 10 Things I Hate About You (1999), she’d played largely anonymous BFFs to white protagonists; high schoolers devoid of much inner life or clear story arcs. Union wasn’t alone in the genre back then. Get Over It (2001), Can’t Hardly Wait (1998) and Never Been Kissed (1999) are just some of the films that feature characters of colour as sidekicks and bit players in otherwise all-white ensembles. Many of the actors playing them were already famous but that didn’t make much difference, either – Fresh Prince star Tatyana Ali briefly pops up as a cheerleader in Jawbreaker (1999), while Lil’ Kim may have been the biggest female rapper in the world in 1999 but she still barely has lines as a prom queen hanger-on in She’s All That.

Race was rarely acknowledged in the Nineties teen movie. Before Isis in Bring It On, only Dionne in Clueless, portrayed by Stacey Dash, was allowed the same dynamism, personality and screen time as her white co-stars. Bring It On isn’t flawless in its treatment of race. The film’s trailer suggests that the Clovers had far more scenes in its original cut, but the fact that Bring It On made race such a fundamental part of its narrative, all while exposing white ignorance in the process, was wildly subversive for the era. It also results in something far less problematic than many of its peers today.

Teen movies capture their young audiences early but, after a while, they also tend to disappoint us – as we grow older, our politics and moral stances shifting, they stay the same, forever trapped in a Juicy Couture tracksuit. It means we spend a lot of time excusing the films we once held dearest to us, forcing us to bite our lips at the Asian jibes in Mean Girls (2004), or the apparent need to give Rachael Leigh Cook a makeover in She’s All That. We can exhale over Bring It On. A film ahead of its time 20 years ago feels just right for today – not altogether flawless, but smart and incisive and admirably invested in the bigger picture.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments