The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

The Brat Pack: Their 10 greatest films, from The Breakfast Club to Sixteen Candles

‘The Breakfast Club’ was released in the UK 35 years ago this week. To celebrate, Clarisse Loughrey explores the work of one of cinema’s most influential clan of actors

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

In spring 1985, New York magazine writer David Blum was sent to profile the young star of St Elmo’s Fire, Emilio Estevez. With his hard-set jaw and neatly coiffed wave of blond hair, the actor always looked like he’d just stepped off a New Hampshire yacht (his father is Apocalypse Now star Martin Sheen). Blum followed him around Los Angeles for a few days. Two incidents jumped out to him – a trip to the cinema saw Estevez effortlessly secure himself a free ticket. Then, while in the company of Rob Lowe and Judd Nelson, the actor was mobbed by female fans at the Hard Rock Cafe.

The youthful, casual aura that encircled him, the tightness of his celebrity clique, and the touch of entitlement to his behaviour led Blum to coin the term “Brat Pack” and christen Estevez as its leader. Like Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis Jr and Dean Martin before them, these were performers whose reputations as dedicated party animals threatened to overshadow their status as thespians. Estevez hated the term, accusing Blum of ruining his life.

It’s debatable how much of a negative impact the term had on the careers of Estevez and his pals, but it’s still useful today in describing what was a tight web of collaborators. Around Estevez orbited the likes of Lowe, Nelson, Demi Moore, Anthony Michael Hall, Andrew McCarthy, Molly Ringwald and Ally Sheedy. John Cusack, Robert Downey Jr and Tom Cruise sat somewhere on the edges.

The films they starred in together represented a new wave in Eighties cinema. After the pessimism and paranoia of the Seventies, Hollywood began to tell stories about teens that made sense to teens. And they were filled with stars that seemed both aspirational and relatable. For the most part, they weren’t the greatest of films, but they served their audience well – most influential of all was John Hughes’s The Breakfast Club, which turns 35 this week. To celebrate, here’s a countdown of the 10 best Brat Pack films.

10. St Elmo’s Fire (1985)

It’s the film that helped birth the term “Brat Pack”. Unfortunately, it’s also desperately hollow. St Elmo’s Fire is an imitation of Hughes’s style by a director of an entirely different breed, Batman Forever’s Joel Schumacher. Far from talking directly to its younger audience, it treated them as if they were an alien species – a parade of hollow, unlikeable stereotypes delivered with a smattering of cynicism. And yet, its central clan of Georgetown University graduates – played by Judd Nelson, Ally Sheedy, Andrew McCarthy, Demi Moore, Emilio Estevez, and Rob Lowe – still feel strangely definitive. The starriness of the film’s cast, its yuppie aesthetics, and its messy, heightened emotions meld together into a fitting, if not entirely appealing, portrait of Eighties excess.

9. Less Than Zero (1987)

Schumacher’s yuppie paradise was quickly overshadowed by the true master of this world, Bret Easton Ellis. Marek Kanievska’s Less Than Zero is loosely based on Ellis’s debut novel of the same name, starring Andrew McCarthy as Clay, a privileged college kid who comes home for the holidays, only to discover that his ex-girlfriend Blair (Jami Gertz) and friend Julian (Robert Downey Jr) are free-falling into a netherworld of cocaine and despair. Cinematographer Ed Lachman, who also worked on Carol (2015) and The Virgin Suicides (1999), captures the slick, superficial beauty of Beverly Hills. But Ellis initially hated the film. No wonder – it tempers his trademark nihilism and slides too easily into finger-wagging moralism.

8. Weird Science (1985)

In 2018, Molly Ringwald, John Hughes’s closest collaborator, wrote an essay in The New Yorker about a “glaring blind spot” in the director’s work. His origins were in the bawdy, frequently racist and misogynistic writing rooms of the National Lampoon magazine. As Ringwald explains: “There was still a residue of crassness that clung, no matter how much I protested.” Those old habits certainly reared their head in Weird Science. Granted, it’s surprising that Hughes could find as much heart and soul as he did in his story of two nerds (Anthony Michael Hall and Ilan Mitchell-Smith) who use their computer skills to create the perfect woman (Kelly LeBrock, who does a superhuman amount of heavy lifting here). But, still, it’s a story where every woman exists as a tool for men’s own emotional needs.

7. One Crazy Summer (1986)

A spiritual sequel and direct follow-up to 1985’s Better Off Dead, the film saw director Savage Steve Holland once again call on John Cusack to play the sweet, disarming loser – a part he’d come to perfect in the Eighties. One Crazy Summer is stupendously silly, an exhaustive onslaught of puerility. Some of the jokes land; many don’t. But it’s enough to get by. Cusack’s Hoops, a cartoonist and frustrated basketball player, travels to Nantucket for the summer. His teenage antics see him cross paths with Cassandra (Demi Moore), a young rock singer, and Egg (Bobcat Goldthwait, delightfully incoherent).

6. Young Guns (1988)

Christopher Cain’s Young Guns is original, at least. Not many would think to do a frat-house take on the classic western. And it wears its Brat Pack credentials with pride, with a cast featuring Emilio Estevez (as famed outlaw Billy the Kid), Kiefer Sutherland, Lou Diamond Phillips, Charlie Sheen (Estevez’s brother), Dermot Mulroney and Casey Siemaszko. These wild, young men turn to bloodshed after their employer (Terence Stamp) dies at the hands of a rival (Jack Palance). Young Guns is all shoot-outs and effusive declarations of brotherhood – the closing narration reveals someone made a secret carving into Billy’s headstone. It read only one word: “PALS”.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

5. Sixteen Candles (1986)

In her New Yorker essay, Molly Ringwald succinctly outlined the problems at the heart of Sixteen Candles: Long Duk Dong, the film’s outrageous racist caricature, and an implied date rape that’s played for laughs. Those fundamental issues are inseparable from Sixteen Candles’s legacy. But the film can elsewhere demonstrate Hughes’s immense empathy for the teenage condition. Ringwald’s Sam Baker is a privileged white girl whose deepest miseries extend to her benign but neglectful parents forgetting her birthday and a worry that the boy she’s crushing on (Michael Schoeffling) may not feel the same way. But the director doesn’t patronise her. In Sixteen Candles, he explores a teenager’s fitful search for acceptance and a sense of identity.

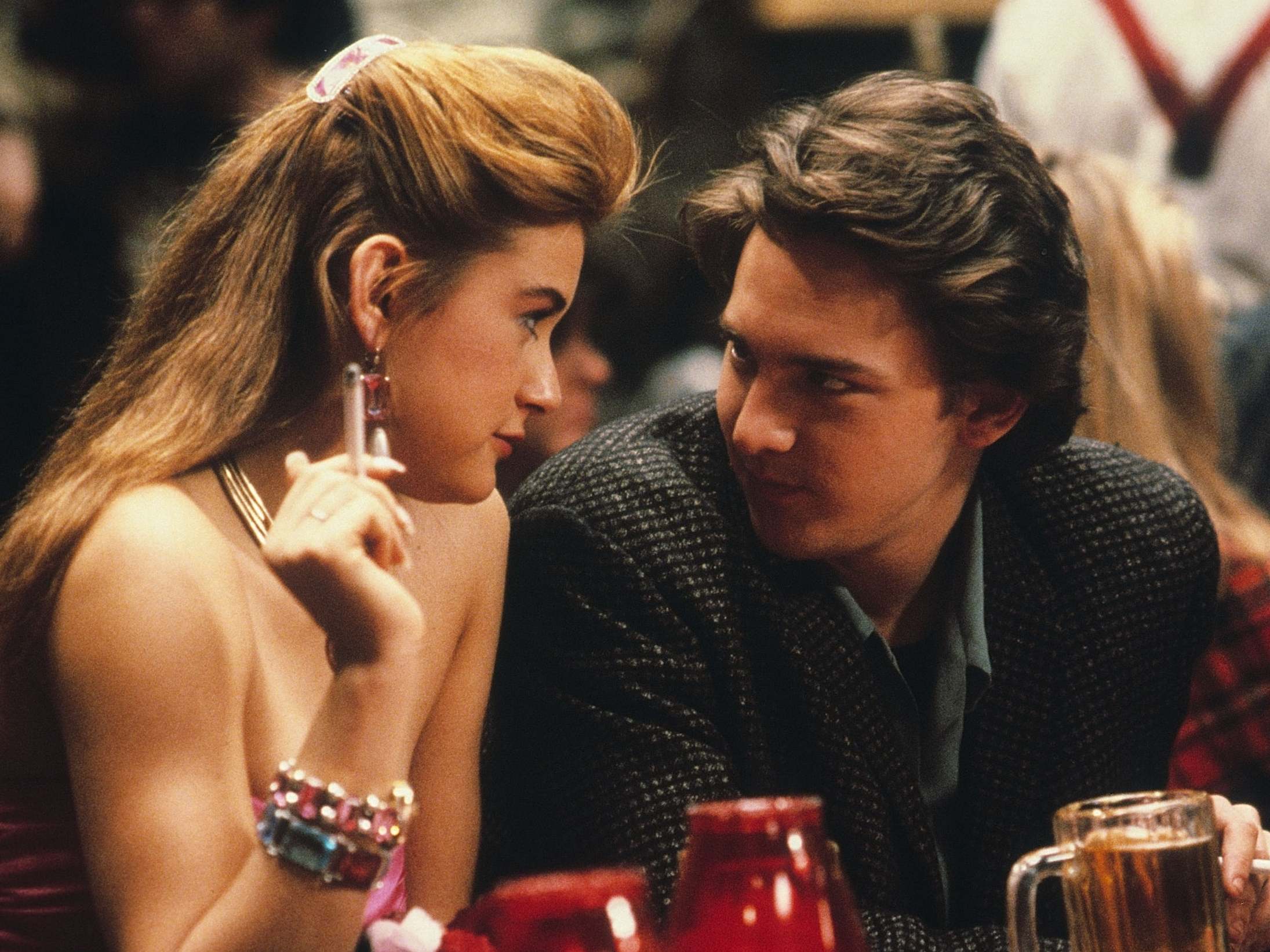

4. About Last Night... (1986)

In a move similar to Less Than Zero, the film takes David Mamet’s prickly writings and smooths them out for the silver screen. About Last Night is loosely based on his 1974 play Sexual Perversity in Chicago, maintaining some of the more controversial dialogue, confidently delivered by Jim Belushi, but finding a novel tenderness. An ad agency artist (Demi Moore) and a restaurant supplier (Rob Lowe) have a one-night stand, but find themselves drawn back to each other time and time again. In charting the ups and downs of a cagey love affair, the film strikes at the crushingly familiar.

3. Pretty in Pink (1986)

Pretty in Pink arrived hot on the heels of The Breakfast Club and Sixteen Candles. John Hughes wrote the script, but passed directing duties off to Howard Deutch. Cast as his lead, of course, was Molly Ringwald. At this point, she’d become less of a singular actor than a teenage force of nature – she was 17 at the time of release. In the role of Andie Walsh, she brought jittery nerves mixed with quiet resolve. She’s a working-class kid striving to support her single, underemployed father (Harry Dean Stanton). Her best friend Duckie (John Cryer) is secretly in love with her, but Andie’s eyes are set on one of the school’s “richies”, doe-eyed Blane (Andrew McCarthy). Pretty in Pink isn’t exactly nuanced in its exploration of class, but it treats Andie’s sense of social isolation with sincerity and care.

2. The Breakfast Club (1985)

The Breakfast Club features John Hughes at the height of his powers. The ingenious move here was to take a semi-theatrical approach. The film focuses on five teens, trapped in Saturday detention. They’re mostly confined to one room. And so, the focus becomes about words and gestures. Hughes took rigid archetypes – the brain (Anthony Michael Hall), the athlete (Emilio Estevez), the basket case (Ally Sheedy), the princess (Molly Ringwald), and the criminal (Judd Nelson) – and forced them to confront each other in a place without escape or social protection. At first, it’s in ways that are merely coded: in looks, shrugs, and “whatevers”. Eventually, they start to reveal their personal experiences and inner lives, using words that are unadorned and uncomplicated. The Breakfast Club’s influence on the teen movie can’t be understated.

1. The Outsiders (1983)

The word “Brat Pack”, at this point, conjures up nothing but nostalgia. It not only harkens back to a world of oversized jackets, padded shoulders, and hairspray-choked up-dos, but to the fragile innocence, deep-rooted bonds, and cherished freedom that comes with youth – in any decade. Francis Ford Coppola’s The Outsiders is filled with recognisable faces: Matt Dillon, Patrick Swayze, Rob Lowe, Emilio Estevez and Tom Cruise. But it deals mostly with nostalgia in that second, more lyrical sense. Adapted from the beloved novel by SE Hinton, the film focuses on two warring factions in an Oklahoma high school: the working-class greasers and the rich “South Side Socs”. When a skirmish ends in bloodshed, the greaser culprits go on the run, with ultimately tragic results. Coppola takes inspiration from Hollywood’s Golden Age here – his characters are bathed in rich colours that seem always to border on artifice. Youth, to this director, is like some half-forgotten dream.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments