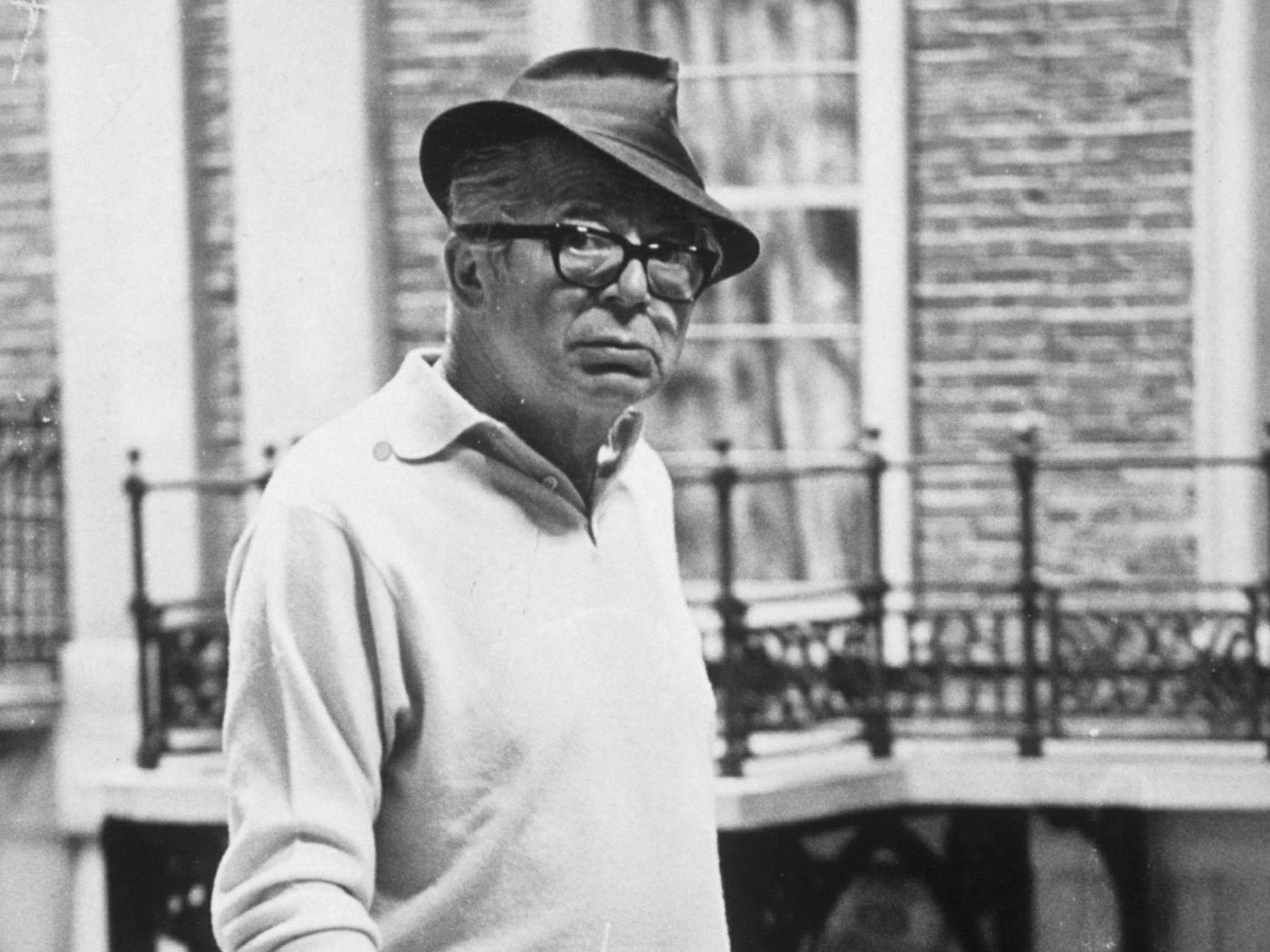

Billy Wilder: Reconsidering the final chapter of Hollywood's most revered and overlooked director

Geoffrey Macnab speaks to film historian Joseph McBride ahead of the re-release of Fedora

Billy Wilder’s filmmaking career ended without him actually noticing the fact. There came a point after his final two movies, Fedora (1978) and Buddy Buddy (1981), when Hollywood simply stopped financing his work. His hopes of directing Schindler’s List as a swansong were also dashed.

In the last 20 years of his life, Wilder (who died in 2002) managed the unlikely feat of being both revered and ignored. He accumulated numerous lifetime achievement honours to add to the six Oscars he had already won. His peers in Hollywood were all too ready to give him a standing ovation when he won the Irving Thalberg award in 1998 – but that didn’t mean that any studio would invest in his screenplays.

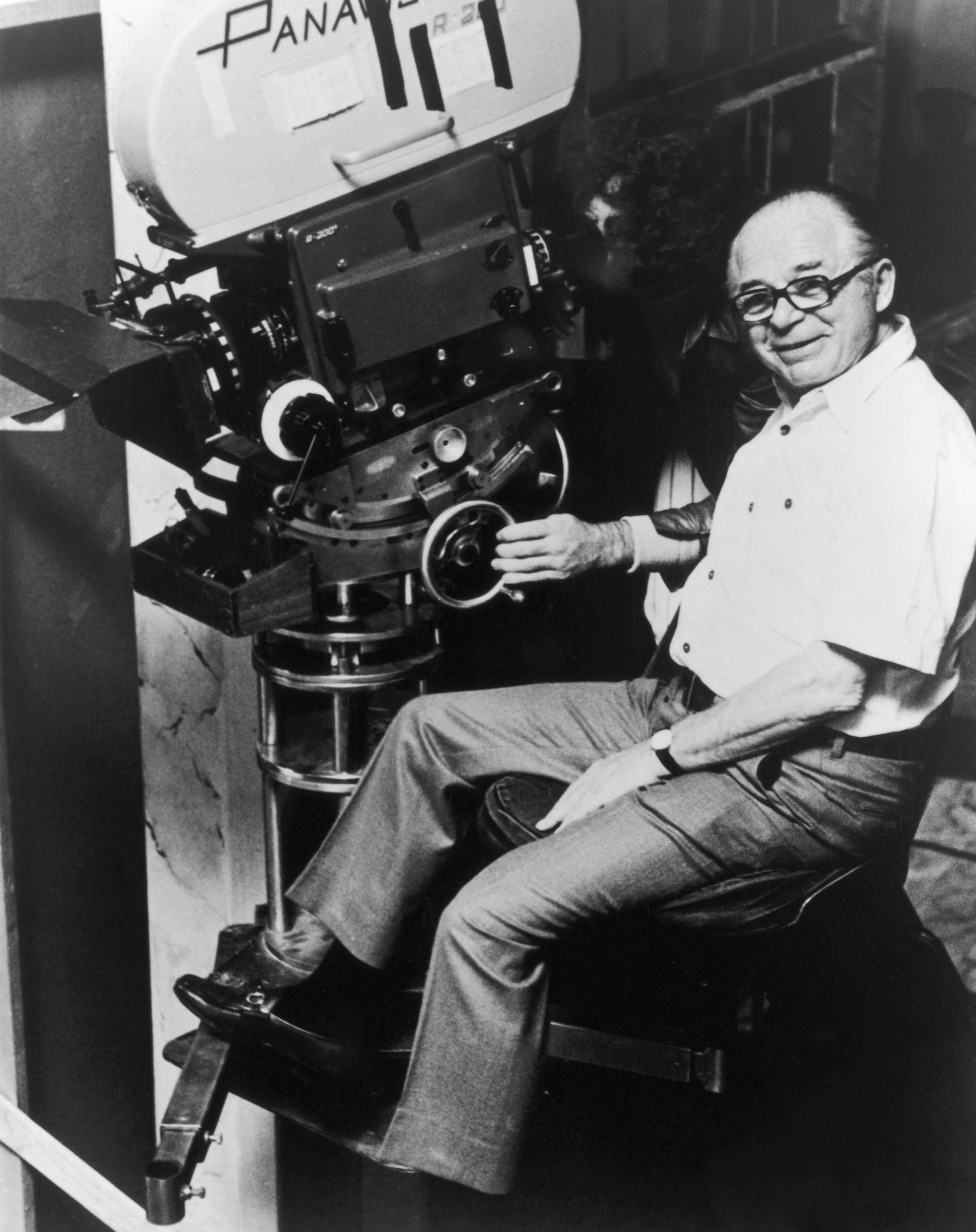

“I was retired but I didn’t know it, because I was too busy and working too hard,” Wilder later told his biographer, Charlotte Chandler. He went every day to his office in Beverly Hills to work on projects that would never be made. He and his writing partner IAL Diamond (who died in 1988) would “get to the office at nine o’clock in the morning, like employees of a bank.”

The hitch was that a younger generation of studio executives didn’t know who he was – and an older generation had decided he was no longer “bankable”.

The re-release of Fedora, one of Wilder’s most unjustly neglected films, provides an opportunity to consider the final chapter in this brilliant director’s career. The film, often seen as a companion piece to Sunset Boulevard, has a famous line, uttered by its struggling film producer hero, Barry “Dutch” Detweiler (William Holden). “It [Hollywood] is a whole different business now. The kids with beards have taken over.” Dutch is trying to coax an old movie star (Marthe Keller) out of retirement, a 62-year-old who, miraculously, still seems to look as youthful as in her heyday.

In the Easy Riders, Raging Bulls era, Wilder, like “Dutch” Detweiler, was a man out of time. Next to the Vietnam movies, the films about vigilantes or the blood-drenched Peckinpah westerns, the wit, sophistication and risqué humour in his pictures seemed to belong to another age. Confronted with The Exorcist and its famous scene of the possessed teenager (Linda Blair) peeing on the floor, Wilder’s response was that if he was making such a film, he simply wouldn’t know where to put the camera.

Throughout these latter years, journalists and filmmakers made the pilgrimage to visit him in his office. Young American director Cameron Crowe published a book-length interview with Wilder. German director Volker Schlöndorff directed a revealing three-hour documentary, Billy, How Did You Do It?. Wilder was befriended by the Spanish director Fernando Trueba. Their friendship began after Trueba won an Oscar for Belle Epoque and said in his speech: “I would like to believe in God in order to thank him. But I just believe in Billy Wilder ... so, thank you Mr Wilder.” Wilder responded by calling him up.

“Every time I arrived in Los Angeles, before I opened the bar or went to the bathroom after 12 hours of flying, the first thing I did was call Billy Wilder,” Trueba remembered. They’d then meet up and talk about almost anything other than Wilder’s movies.

In spite of his achievements, Wilder simply couldn’t get work. Buddy, Buddy (a remake of a French movie) had been one of his least successful films - but the reason he had made it was simply that it was offered to him.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Hollywood history is littered with stories of once acclaimed directors fallen on hard times. Wilder, though, was very well off. When he decided to sell a large part of his art collection (which included works by Picasso, Miro and Giacometti) at Christies in the late 1980s, the collection fetched $32.6m. He had enough money to finance his own movies – but realised that there wouldn’t be much point unless he was able to secure them distribution too.

Wilder’s struggles to make Fedora mirrored that of the producer played by William Holden in the movie, trying to lure the mysterious old star out of retirement. When Universal refused to back the project, he sought German tax shelter support instead. The film premiered in Cannes to mixed reviews. Buddy, Buddy didn’t do any better but Wilder and Diamond carried on developing projects, convinced they were due another hit soon.

Film historian Joseph McBride, who interviewed Wilder several times, remembers that Wilder had one script which he jokingly referred to as The Foreskin Saga. This was about HB Warner, the English actor who played Christ in Cecil B DeMille’s The King Of Kings (and later appeared in Sunset Boulevard). Warner was a notorious drunkard and lecher. Keen to avoid scandal, the studio forbade him from going to brothels and bars in Los Angeles when he was playing Jesus – so Warner headed down to Tijuana in Mexico to get his kicks there instead. That film didn’t happen nor did a planned comedy about Le Pétomane, the French music hall artist renowned for his skill at farting.

With Diamond’s death, Wilder lost momentum. He was always at his best as a writer when he had a writing partner – someone to disagree with. (“My theory about collaborators is that if there are two guys that think the same way, that have the same background, that have the same political convictions and all the rest, it’s terrible. It’s not collaboration. It’s like pulling on one end of the rope,” he wrote.) Wilder’s expertise didn’t go entirely to waste. He is said to have worked briefly as script consultant – but his caustic appraisals of other people’s screenplays didn’t endear him to his bosses.

There were very personal reasons for Wilder to want to make Schindler’s List in the early 1990s. Many of his relatives had died in the Nazi era. He escaped Hitler’s Germany by the skin of his teeth in 1933, leaving his Berlin apartment to catch a night train to Paris just a few minutes before the Gestapo came for him. In 1945, he was a supervising editor on Death Mills, a documentary filmed in the Nazi concentration camps. McBride remembers that when confronted with Holocaust deniers, Wilder’s response was to say that he had only one question for them – where is my mother?

Universal executive Sid Shainberg had optioned Schindler’s List for Spielberg in 1982, when Thomas Keneally’s book was published. At first, Spielberg was reluctant to take on the project. There was talk of Martin Scorsese directing it. The project was offered to Roman Polanski. Eventually, Wilder contacted Spielberg, saying he wanted to direct the film as a memorial to his family members who had perished in the camps. “Schindler’s List – it would have been something of my heart, you know,” he told Cameron Crowe. McBride points out that the film has thematic overlaps with Wilder’s other work. It was about a con man trying to pull off an elaborate con, albeit that Schindler’s hoodwinking of the Nazis was for altruistic reasons. By then, though, Spielberg was already in pre-production on the movie. It was too late. There was no longer any possibility of Wilder, who was very old by then, directing it.

Whatever his disappointments, Wilder praised Spielberg’s film (“a very, very good picture”). He himself didn’t direct again unless you count a skit with Walter Matthau and Jack Lemmon that he put together for the Writer’s Guild as a tribute to I.A.L Diamond following Diamond’s death.

“It was a real waste of his talent. I find it lamentable that they (the studios) couldn’t find $2m or $3m here or there to let Wilder make a film,” McBride says of Wilder’s barren later years in Hollywood when he was, effectively, in “internal exile”. Still, it wasn’t such a bad career: he did manage to spend more than 50 years making movies. From Some Like It Hot to Sunset Boulevard, From The Apartment to Double Indemnity, many Wilder movies have long since been acknowledged as cast iron classics.

A new restored version of Billy Wilder’s Fedora is released on Blu-ray and DVD as part of Eureka Entertainment’s Masters of Cinema series in September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

17Comments