From Barbie to Babylon: The 15 best films of 2023

Leonardo DiCaprio grimaced. Mia Goth killed. Margot Robbie had at least three existential crises. But which of their films came out on top? Our chief critic Clarisse Loughrey has counted down the very best movies of the year in cinema

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When it comes to cinema, 2023 has been a year of extremes. Barbenheimer. Industry strikes. Cancelled projects. Rallying audiences. Political censorship. To spend it writing about the industry and its art has involved ricocheting between hope and despair, between having faith that cinema will flourish again, and having to watch it fight tooth and nail for its very survival.

There were, however, 15 films that demonstrated empathy, vision, and creative courage. They showed that, whatever the future holds, we can at least be sure that great art will always prevail.

Here, based on UK release dates, are the best films of this past year.

15. Reality

Playwright Tina Satter’s feature film debut is rooted in sheer, minimalist terror, and made urgent by its approximation to the truth. Reality, as in the film version of the play Is This A Room? that Satter staged in 2019, is a verbatim adaptation of the FBI’s interview with US Air Force veteran and NSA-contracted translator Reality Leigh Winner, on 3 June 2017. Winner was accused of leaking an intelligence report on the attempted Russian hacking of voter rolls during the 2016 election, and sentenced under the 1917 Espionage Act. But these weren’t the actions of a well-trained spy, but of an ordinary person whose humanity turned her by law into a criminal.

We watch Winner (Euphoria’s Sydney Sweeney) fuss over her pets as her home is invaded by an army of men who speak in low, casual grunts. She apologises for the mess and tries to find a private space where she can talk to the pair in charge, Garrick (Josh Hamilton) and Taylor (Marchánt Davis). They speak with mechanical politeness, as we, the audience, start to fathom the profound denial at work here. No one says it in these ripped-from-reality transcripts, but by the end of the day, this woman will be in jail.

Read our interview with director Tina Satter

14. How to Have Sex

Molly Manning Walker’s gut-punch of a debut is a tale of two halves. Tara (Mia McKenna-Bruce) turns up in Malia, Crete, with her two friends, Skye (Lara Peake), and Em (Enva Lewis), and a stubborn determination to lose her virginity. She’s 16, fleeing a rapidly onsetting adulthood, and would rather drink herself into oblivion than read what’s inside the envelope of her GCSE results.

At first, the cycle of drink, drink, drink, puke, sleep, drink, drink, drink is draining but alluring. Then Walker upends both her audience and Tara herself, as the resort’s ugly, exploitative side crawls out of the shadows. It’s as if we’ve hit the end of the night, and someone’s finally turned the lights on over the dancefloor. How to Have Sex is a loosely autobiographical work from a first-time director too smart and too empathetic not to look at the world of sex and consent with anything but brute honesty.

Read our original review, and our interview with star Mia McKenna-Bruce

13. May December

May December is firmly the work of Todd Haynes the provocateur, the artist who once dramatised Karen Carpenter’s struggles with anorexia and bulimia using Barbie dolls in his short film Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story. It’s (very) loosely based on the story of Mary Kay Letourneau, an American teacher jailed in 1997 for sexually abusing a 12-year-old child. She gave birth to the boy’s daughter, and later married him. But Haynes, at first, shades his story in the same way the media did – as pure tabloid sensation.

An actor (Natalie Portman) turns up on the doorstep of Gracie (Julianne Moore), this film’s Letourneau. She’s playing her in an upcoming film and is eager to mirror all of Gracie’s affectations, from her lisp to the self-conscious way she tilts her head, like a doting princess. May December is an opportunity for two of Hollywood’s most divine stars to conduct a secret battle, one contained almost entirely within unfinished sentences and twitching eyebrows. But, then, Joe (Charles Melton), Gracie’s victim and husband, shifts into focus. The heartbreak of Melton’s performance – and our complicity in the melodrama that came before it – is almost too much to bear.

Read our original review, and our interview with director Todd Haynes

12. Priscilla

Sofia Coppola’s take on The Little Mermaid may have been thwarted by the powers that be (read: unimaginative studio execs), yet the director found her own subtle, subversive form of retaliation in Priscilla. It’s its own fairytale, a tragic version of Sleeping Beauty in which the princess wakes up from her eternal slumber only to realise that it’s her prince who cursed her in the first place. Here, though, the prince is that icon of modern Americana, Elvis Presley. Coppola’s film also works as an unexpected companion to last year’s Elvis, in which Baz Luhrmann and his star, Austin Butler, brought the singer’s legacy into rocket-fuelled, rhinestone-encrusted reality.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

But if Butler, brow slicked with sweat, embodied Elvis the showman, then Jacob Elordi, in Coppola’s film, looks behind the curtain to find a nervous, insecure wretch desperate for an accessory to his misery. Working off Priscilla’s own memoirs, published in 1985, Coppola’s quiet but evocative work draws Cailee Spaeny’s Priscilla into a kingdom of whispered promises, gold watches, and white shag carpets. Spaeny plays her as a young girl caught up in a daydream – but, in her few moments away from Elvis, she’s like a whole other woman.

Read our original review

11. Passages

While Celine Song’s Past Lives will likely make it onto quite a few best-of-the-year lists, I couldn’t help but find myself drawn more towards that film’s spiritual antithesis: Ira Sachs’ Passages, which counters the maturity and clarity of Song’s protagonists with a trio of lovers headed towards mutually assured destruction. German director Tomas (Franz Rogowski) – spoiled, petulant, pitiable – is married to English printmaker Martin (Ben Whishaw). On a night out, Tomas sleeps with a French schoolteacher, Agathe (Adèle Exarchopoulos).

He rushes home to tell Martin – “I had sex with a woman. Can I tell you about it?” – and thus ignites a carnal firestorm, in which everything around Rogowski’s big, fawn eyes and impish smile seems to catch the light. He’s so fragile that you yearn to comfort him, but so capable of out-and-out cruelty. Sachs takes no sides here – his camera, instead, thinks carefully about where true power lies, in life and in sex. It’s an anthropologist’s eye being applied to the most glorious of messes.

Read our original review, and our interview with director Ira Sachs and star Franz Rogowski

10. Rotting in the Sun

Nihilism collides with (possibly?) the largest gallery of onscreen penises this year in Sebastián Silva’s cutthroat portrait of art, fame, and wealth. The Chilean filmmaker plays a version of himself, who is driven to suicidal ideation by the alienation he experiences in his own extremely privileged, narcissistic corner of gay culture. He obsessively researches phenobarbital, a drug linked to a sudden spike in lethal overdoses, and attempts to prove that his life is meaningless because he can’t remember the last film Martin Scorsese directed.

It’s performative and sincere at the very same time, a parody of artistic self-flagellation that twists into unexpected patterns once the film’s other players make their entrance. One is influencer Jordan Firstman, a credited writer on TV’s Search Party, who again plays himself in no-holds-barred form, desperate here to collaborate with Silva on a reality show that he describes as Curb Your Enthusiasm “but, like, positive”. The other is Vero (Catalina Saavedra), Silva’s cleaner, who brings this audacious but oddly mournful story to a close with a single shot that’s really a kick to the teeth.

Read our interview with star Jordan Firstman

9. The Eternal Daughter

Joanna Hogg’s dual films, The Souvenir and The Souvenir Part II, struck a chord with critics and viewers, thanks partially to how their autobiographical conceit encompassed some of film’s knottiest questions: whose stories are we allowed to tell? And what do we hope to achieve by telling them? Such themes lie, too, at the heart of Hogg’s unexpected, deeply affecting third chapter in the trilogy, The Eternal Daughter.

Hogg’s stand-in Julie was played in those first two films by Honor Swinton Byrne. But here Julie is middle-aged, and played by Swinton Byrne’s real-life mother Tilda. Julie’s own mother, Rosalind, is also played by Swinton – meaning the chameleonic actor is given the great pleasure of acting opposite herself. Julie takes Rosalind on a birthday weekend to a manor hotel in Wales, a former private residence where Rosalind spent a part of her childhood. Mother starts to reminisce while daughter, ever the filmmaker, guiltily hits record on her phone. Unlike its predecessors, though, The Eternal Daughter seems to exist in its own, haunted realm of fog and shadows. Gothic literature often treats the home as a psychic realm of lingering memories – here Hogg uses it to explore a child’s desperate need to be understood and loved by a parent.

8. Barbie

Hollywood hasn’t entirely been bereft of good ideas this year – take, for example, John Wick: Chapter 4 or Marvel’s Guardians of the Galaxy Vol 3. But you’d probably have to dial back to Mad Max: Fury Road to find a more robust example of art conquering commerce than Greta Gerwig’s Barbie. It’s a film about a toy, that’s also a joyous slapstick comedy that harkens back to Hollywood’s golden age, that’s also a surprisingly solid examination of depersonalisation under capitalism. Its box office success, coupled with the entire Barbenheimer phenomenon, felt like a brief but welcome ray of hope for the industry.

And it’s that ingenuity, and optimism, that drives Gerwig’s film as it dances across film history – from Jacques Demy’s The Umbrellas of Cherbourg to Pee-wee’s Big Adventure – while embracing the hypocrisies of modern life. Margot Robbie’s Barbie, “the Stereotypical Barbie”, journeys from her perfect, plastic world into our own, only to discover that the words “women can be anything” have been twisted into “women should be everything”. Oh, and Ryan Gosling’s Ken is there, too – and he’s very, very funny.

Read our original review

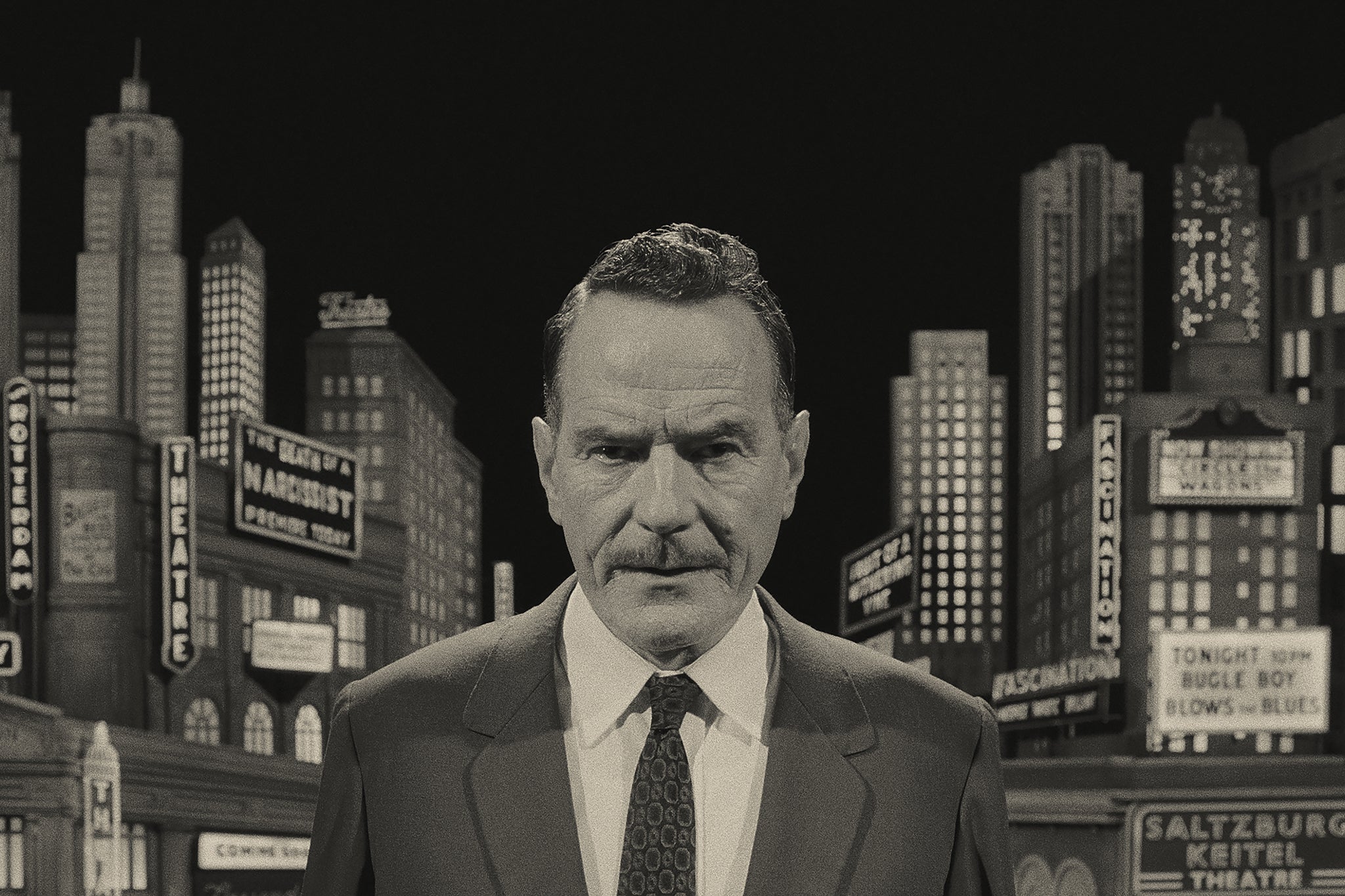

7. Asteroid City

Wes Anderson’s immaculate dioramas of human frailty have always been obsessed with the idea of fiction and those who rely on it – the writers, schemers, romantics, and the tragically delusional. Yet, his latest feature, Asteroid City, finds those fictions so densely layered, like a mille-feuille pastry, that it represents a kind of apex for the filmmaker. It’s the Andersonian equivalent of breaking the sound barrier. A host (Bryan Cranston) introduces a black-and-white television show about the production of a stage play, itself about a government’s attempts to conceal proof of extraterrestrial life. We see the television show, the stage production, and the fictional story all play out in different palettes and dimensions.

But, deeper still, lies more fiction. A war photographer (Jason Schwartzman) uses his trauma as a way to fend off the duties of fatherhood. An actor (Scarlett Johansson) fetishes the addictions, abuses, and untimely deaths of her famous peers, as an easy route to chase after more immaterial genius. Another actor (Schwartzman, again) struggles to grasp the meaning of the play and is told, in return, “It doesn’t matter. Just keep telling the story.” Asteroid City offers sanctuary to the soul-sick and lost.

Read our original review, and our interview with director Wes Anderson

6. Babylon

Damien Chazelle’s debauched, provocative take on Hollywood’s silent era tears through both the director’s La La Land reputation as a head-in-the-clouds dreamer and the common misconception that early film was ever a quaint or saintly place. We enter this world of drugs, sex, and elephant dung through the eyes of two ravenous wannabes, Nellie LaRoy (Margot Robbie) and film assistant Manny Torres (Diego Calva), both fictional amalgamations of the era’s true pioneers.

Robbie, here, delivers the starlet with a lion’s bite, as she wrestles with snakes, dances like a woman possessed, and leaves a table of hors d’oeuvres looking like a murder scene. She crashes through Chazelle’s vibrant but rarely inauthentic world, through Justin Hurwitz’s feet-stomping jazz score and Mary Zophres, Jaime Leigh McIntosh, and Heba Thorisdottir’s sultry fashion looks. Her performance encompasses both glory and heartbreak, as the film around her begins to confront the cost of immortality – and what it takes to achieve that one perfect moment on screen, like the single tear that rolls down Nellie’s cheek in her first on-camera performance.

Read our original review

5. Saint Omer

In 2016, French documentarian Alice Diop shadowed the trial of Fabienne Kabou, a Senegalese woman charged with killing her infant daughter by leaving her at the beach. Saint Omer, her formidable shift into fiction, allows us to understand what exactly about the experience so rattled and fascinated her. It’s a film about empathy and unknowability, about how France’s colonial history manifests into modern-day isolation. Kabou’s trial is refracted not only through Diop’s own subjectivity as a witness, but through the tragedy of Medea, the matricidal Greek princess scorned as “utterly hateful to the gods… and to the whole human race”.

Saint Omer attempts to strip the crime of its “unthinkability”, drawing its power from the futility of that act. The accused here, Laurence Coly, is played with stunning reserve by Guslagie Malanda, who eschews expression and instead fills the void with unnameable, suppressed passion. We spend the entire film desperate to see her cry, to see her rage, to unravel in a way that would finally provide answers. But that moment doesn’t come. Instead, cinematographer Claire Mathon sees her shrink almost into nothingness, save for the few brief, but potent glances she shares with Diop’s stand-in, Rama (Kayije Kagame).

4. Pearl

At first, Pearl was nothing but an afterthought, a prequel to Ti West’s Seventies porno-slasher X, hastily written in two weeks with his star Mia Goth. But art has odd ways of taking on a life of its own. Pearl not only far outmatches its predecessor, but actually serves better as a standalone, tragicomic portrait of a woman whose sensitivity to the world ultimately destroys her. Goth’s Pearl is a monster of very modern makings, of sorrow and violent desires, and corrupted to the point she can no longer differentiate between the pure and the abject.

She’s a young woman, living on a farmstead in 1918 and the daughter of agoraphobic German immigrants, who sees abuse at home and a Technicolor wonderland in her delusions. But she’s betrayed by those she trusts time and time again. When a handsome cinema projectionist (future Superman David Corenswet) sees a glimpse at the real Pearl, and all her ugly emotions, he cowers. Murder and mayhem ensue. Goth embraces all that is scary, ludicrous, and pitiable about Pearl, and allows those feelings to reach their apex in a final reel monologue that becomes a slam-dunk moment for the actor. Long live Pearl, warts and all.

Read our original review, and our interview with director Ti West

3. All the Beauty and the Bloodshed

Not only does beauty and bloodshed lie within Laura Poitras’s documentary on artist Nan Goldin, but so does resilience, grief, elation, desire, freedom, fury, chaos – every shade of every emotion signalled as big and bright as a Times Square billboard. Here, as in its subject’s life, there’s little delineation between life, art, and politics. Goldin’s unhappy childhood, in which misery was suppressed behind a suburban facade, was marked by the suicide of her sister. That pain led to her work, including 1985’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, which catalogued the fortifying but vulnerable queer enclave of New York’s Lower East Side.

With a shutter click, the community comes under attack during the Aids crisis, as Poitras recounts the friends Goldin lost, like artist David Wojnarowicz. Goldin’s grief becomes coupled with the opioid crisis, and her own addiction to OxyContin. It leads her to the steps of the Met, to protest the funding received by the Sackler pharmaceutical empire. At one point, Goldin explains that she became a photographer because she’s spent her entire life being told her own experiences weren’t real. A camera is one small way to preserve the truth. Poitras’s impassioned, soul-scouring documentary captures what happens when art no longer becomes a desire, but a means of survival.

Read our interview with director Laura Poitras

2. Return to Seoul

The homecoming may remain a cornerstone of rosy, heartfelt cinema, but it’s Davy Chou’s fearless attempt to interrogate those ideals that makes Return to Seoul such a profound contribution to this year’s cinematic landscape. Freddie (Park Ji-min), a French woman in her mid-twenties adopted from South Korea at birth, arrives in Seoul to find her birth parents. But, when her father (Oh Kwang-rok) responds, the cavern in her heart only grows deeper and darker.

Sentimentality is a forbidden word here, as Chou’s camera chases Freddie across the span of eight years, as she shifts listlessly between identities – the femme fatale with blood-red lips, the officious arms dealer, the hiker with shorn locks. Park, in her debut performance, lets Freddie’s steeliness bear the weight of a lifetime’s disappointment. She’s a seductress, a wild dancer, and a woman hell-bent on inflicting pain on the city she may never feel worthy of. For anyone living with a question mark over their head, the sense of the unknown can turn into poison.

Read our original review

1. Killers of the Flower Moon

Martin Scorsese’s gallery of gangster masterworks receives a new addition here, with the filmmaker dragging out into the light one of America’s great, suppressed evils. Killers of the Flower Moon adapts David Grann’s 2017 non-fiction book on the massacre of indigenous people that took place within the Osage nation during the early 20th century. Dozens of the Osage were murdered for the oil rights that had made them the richest people per capita on earth, all by white co-conspirators who had married into their families. Scorsese’s film hones in on Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio), who arrived in Fairfax, Oklahoma, and married Mollie Kyle (Lily Gladstone) at the behest of his uncle, William Hale (Robert De Niro).

Here, Scorsese circles around his old obsessions, as he methodically chips away at the rotted core of a man’s heart. It’s no less unflinching in its depiction of violence, and his faithful collaborator, editor Thelma Schoonmaker, lends the film a sickly, apocalyptic propulsion. But it’s also, in part, so clearly the work of a filmmaker in his later years, who is a little more selfless and self-reflective than before.

This film belongs, just as much, to Gladstone as it does to Scorsese, who shapes the film’s tragedies around her fixed but shattering gaze. It belongs, too, to the Osage Nation, who helped form its narrative and worked extensively on its production. Scorsese looks to them, then looks back to himself – and, in the film’s stunning conclusion, attempts to reckon with both the power and futility of his storytelling.

Read our original review, and our interview with ‘Killers of the Flower Moon’ novelist David Grann

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments