Can Zack Snyder bring the zombie flick back from the dead?

As the Justice League director drops Army of the Dead on Netflix, Ed Power considers how the supernatural genre turned not so super, and whether after a year of lockdowns, we’re the zombies now…

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Not for the first time, the zombie movie is about to rise from the grave. In Zack Snyder’s Army of the Dead (the director’s new Netflix feature), pro-wrestler turned big screen strongman David Bautista leads a team of mercenaries in a smash-and-grab raid on a dystopian Las Vegas overrun with animated corpses. Think Ocean’s Eleven trapped in a post-apocalyptic compound with George A Romero’s Night of the Living Dead.

Or maybe take that as a mere starting point. Snyder – who, with his recent recut of DC’s Batman/Superman/ Wonder Woman team-up epic Justice League, reframed the superhero blockbuster as a Nietzschean struggle between spandex-happy übermenschen – is clearly keen to take zombies somewhere new. “They’re not what you think they are,” one of his characters says of the zombie horde. “They’re smarter, they’re faster, they’re organised.”

Reinforcing the sense Snyder has set out to reinvent the zombie genre, the trailer concludes with a rotting albino tiger roaring atop a car. It’s visually stunning and a reminder zombies are not statutorily obliged to be slow-moving and dim-witted. As times change, so does the zombie flick. “Zombies are always popular because you can put whatever current fear exists on their shoulders: are they disease, mortality, death, a viral pandemic, invading armies, etc?” says James Moran, writer of the 2012 British comedy horror Cockneys vs Zombies. “They’re a good substitute for what’s currently bothering us. Because they have no backstory, they can be whatever you like.”

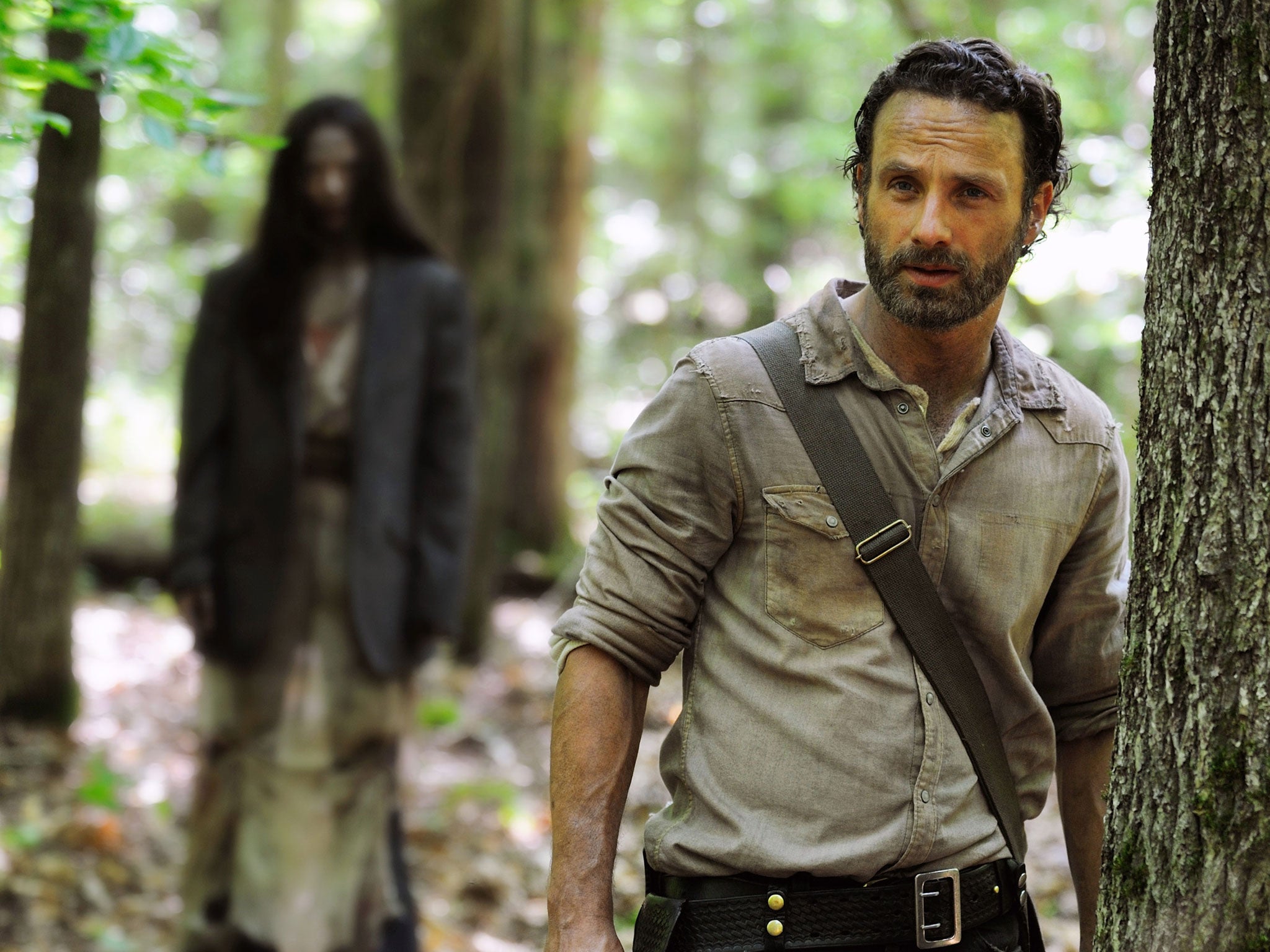

Zombies were slightly on the wane through the past decade. The Walking Dead, once the world’s second most popular television series after Game of Thrones, has lurched into a death spiral. The show devolved into a drab soap opera, the zombies mere window dressing. That slump was reflected in plummeting ratings. Game of Thrones demonstrated zombies had their limitations as the undead army of White Walkers was snuffed out in just a single episode. In one of the biggest anti-climaxes in television history, boss zombie the Night King was cut down in completely random fashion by Arya Stark. As the blow fell, so 10 years of carefully cultivated White Walker mystique turned to dust. Meanwhile, plans for a sequel to Brad Pitt’s 2013 hit World War Z, to be potentially directed by David Fincher, were stalling. Interest in zombies appeared to have shrivelled faster than desiccated human flesh in the sun. And then along came a pandemic. Suddenly allegorical horror about viruses that strip us of our humanity acquired a fresh urgency. Zombies were on their way back to the centre of the zeitgeist.

It’s true that Snyder’s Army of the Dead had been green-lit before Covid. Yet there can be little doubt its portrayal of a world laid low by a deadly zombie contagion has taken on an added resonance. And as we tentatively move into a post-Covid era, this may be the perfect movie onto which we can project our shared lockdown traumas. Zombies have come a long way from their early years as a horror trope. Their first major cultural moment was Romero’s Night of the Living Dead in 1968. The “patient zero” of the genus established many of the cliches that endure to this day: that zombies are slow-moving, brain-dead and look like a cruel parody of their former selves.

The zombies were also, from the outset, deeply allegorical, says Roger Luckhurst, professor in modern and contemporary literature in the Department of English and Humanities at Birkbeck, University of London and author of Zombies: A Cultural History. “Romero’s work was always explicitly coded as a critique of consumer capitalism – that endless hunger to devour everything in Dawn of the Dead [the 1978 Night of the Living Dead sequel, set in a suburban mall].”

The milieu has now taken on new pertinency, says Luckhurst. “Obviously, the pandemic makes the shift to a ‘viral’ contagion feel very relevant – and the global visions of spread in, say, World War Z or the Resident Evil films, now spring into focus.”

At the same time, he says, there has been a growing curiosity about what it must feel like to be a zombie. We’re not quite at the point where movies are giving us zombies campaigning for the right to vote or own property. However, there has been a trend towards portraying zombies as more than just mindlessly destructive. He gives as an example the TV series iZombie, a supernatural thriller from the perspective of a crime-fighting zombie girl, and 2016’s The Girl with All the Gifts, about a child whose humanity is threatened by a “zombifying” fungal infection. “Rather than seeing them as an indifferent mass horde, we’ve had tales told from their point of view,” says Luckhurst.

In horror, trends come and go. In the Nineties, moody vampires were all the rage – whether in the novels of Anne Rice or cult role-playing game Vampire: The Masquerade. Mummies had a moment with the hit Brendan Fraser films of the early 2000s. But despite the diminishing popularity of The Walking Dead, zombies are different in that they have maintained a cultural presence across the decades. That’s because they hold up a mirror to modern society, says Dr David S Smith, psychology lecturer at the School of Applied Social Studies at Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen. “Sometimes we see the best in humanity – movies like Train to Busan, shows like The Walking Dead or to an extent, video games like The Last of Us [to be adapted by HBO] show a world where people can care for others’ children as if they are their own and make real sacrifice,” he explains. “Yet this behaviour is generally portrayed as exceptional. Even when zombies get played for laughs, like Shaun of the Dead, Zombieland, or Santa Clarita Diet, they’re usually used to explore real human conditions: people being bored, conforming to social expectations, going through the motions, or living in a state of arrested development.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

As he says, the zombies portrayed in Shaun of the Dead are only marginally different from the human survivors. They shuffle about grumbling, locked in the same brain-dead routine day after day. Following a year of lockdown, it’s easy to imagine how it feels to be in their rotting shoes. “In that respect, I don’t think we connect with the genre because we’re scared of being turned into zombies,” says Smith. “I think it’s because on some level, we fear that we already are.”

Zombies also remind us of what lies ahead. All going well, we hopefully won’t end up feasting on the brains of our nearest and dearest. But we will all one day become rotting corpses. “Zombies are extremely personal and familiar to all of us. There are no fantasy-based feature changes, no animal alterations, teeth, ears, etc,” says Greg Rudman, founder of Zombie Infection, which stages “immersive theatre” zombie experiences around the UK. “It’s about humanity’s fascination with life and death, specifically about living forever, or what happens when you die.”

Yet some commentators fear zombies have become played out. “Zombie saturation for most fans seems to have been as a result of season after season of The Walking Dead series and its offshoot Fear the Walking Dead,” says Adrian Smith of cult cinema blog Movies and Mania. “Even those that didn’t watch the series became numbed by the saturation coverage. Many fans are, frankly, zombied out.”

But with Army of the Dead, it’s possible Snyder can bring about a zombie resurrection, he says. “Snyder’s film has sparked interest because he partly regenerated the zombie sub-genre with his seminal 2004 remake of Dawn of the Dead,” says Smith. It’s potentially interesting that Snyder’s latest is also a heist,” continues Smith. “Let’s hope it’s a livelier entry that sparks some more interesting takes on the zombie theme.”

Reviews for Army of the Dead are overwhelmingly positive (“a baroque tapestry of blood, bullets and bones,” said the review in The Independent). The sense is that, 17 years from his Dawn of the Dead do-over, Snyder has made another meaningful contribution to the undead oeuvre. And that the zombie movie still has a bit of life in it yet.

Army of the Dead is available on Netflix now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments