Ang Lee: 3D movies shouldn't be about action or spectacle but the opposite

The Oscar-winning director’s new movie, ‘Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk’, about a US soldier returning from Iraq, was a flop in the US because of its hyper-real look, but, says Ang Lee, part of the problem is getting audiences to adjust to technical innovation

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

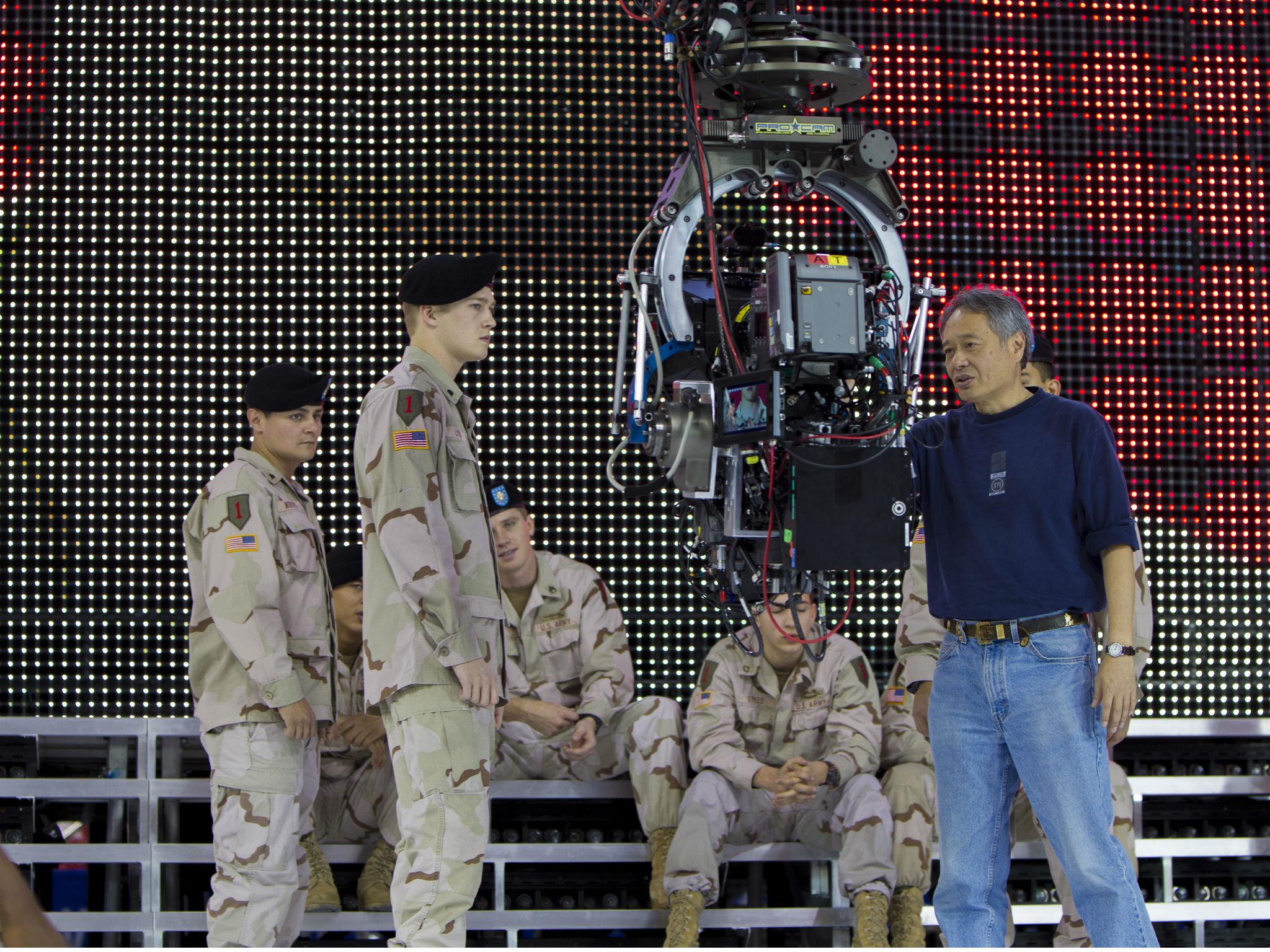

Your support makes all the difference.When Ang Lee’s new movie Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk premiered at the New York Film Festival last autumn, the reactions were not what the two-time Oscar-winning director might’ve hoped for. Based on the 2012 novel by Ben Fountain, the critical objections were less against the story of a US soldier returning from Iraq to homecoming hysteria than the film’s groundbreaking technical innovations.

Using 3D and 4K resolution, Lee and his cinematographer John Toll shot the film at 120 frames per second – almost four times the usual 24fps speed. The result of this higher frame rate lends the film an almost hyper-real look, magnifying the visual clarity to an almost unsettling degree. Much like when Peter Jackson shot The Hobbit at 48fps, some complained about the “soap opera effect”, the undesirable ‘smooth’ quality that some modern HD televisions can produce.

“Realness of emotion overpowered by realness of image,” complained one viewer on Twitter after that first screening, echoing the sentiments of many. When we meet in a London hotel, the 62 year-old grey-haired Lee looks rather dejected; “The movie was hardly seen in the States,” he sighs. “The studio didn’t do much to promote [it].” The film flopped there, taking less than $2 million. It didn’t help that only two theatres – in New York and Los Angeles – were equipped to show the film in its intended 120fps format.

While the film can be screened without this new format, Lee has a right to feel aggrieved. A technical pioneer – Life of Pi truly pushed the boundaries of 3D – his experiments mean that, as trade paper Variety put it, Billy Lynn’s “has the potential to be a revolutionary film”, opening the door for a “new way for [movies] to be experienced”. Too modest to say so, the softly-spoken Lee simply shrugs. “I try to make a difference, but I can only go so far.”

Part of the problem, he says, is getting audiences to adjust; he believes using this new technology shouldn’t just be for blockbusters. “My personal feeling is contrary to what people believe a 3D movie ought to be – a technically advanced movie – which is spectacle or action. In this media, what you get most – an advantage – is an intimacy, the way you engage, the sympathy, with the character. That’s what I found. I know it’s a tough sell, against convention.”

He compares it to the days when CinemaScope was introduced in Hollywood in the 1950s, the widescreen innovation used to battle declining audiences. “It’s a different way of making movies,” he says. “Right now, it takes some reason to see it.” He cites the film’s immersive flashbacks to Billy’s time in Iraq. But in the future, it won’t be confined to action sequences. “When you get used to it, you’ll see [it] more and more,” he promises.

The film stars British newcomer Joe Alwyn as the 19 year-old Billy, who takes centre stage at a celebratory parade at a Thanksgiving halftime show at a Dallas Cowboys’ football match. Lee smartly juxtaposes this surreal hoopla with the horrors faced back in Iraq. “I don’t really see it as a war movie or a homecoming movie,” he says. “It’s more a social study and character study, a movie about growth and faith, rather than a war movie or coming-of-age movie.”

As much as Lee denies it’s a “homecoming” movie, putting it alongside films like Stop-Loss and In The Valley of Elah, it highlights the disparity between civilians’ perceptions and soldiers’ experiences of the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. “I understand that soldiers are bothered when people thank them for their service – because it means they [civilians] don’t have to do it,” Lee says. “If you really care, give them money – jobs and money. Don’t thank them, give them actual help.”

Billy Lynn’s certainly falls into the category of Lee’s American canon – movies like Seventies suburbia tale The Ice Storm, gay cowboy drama Brokeback Mountain (which won him his first Oscar for Best Director) and Civil War-set Ride With The Devil. The New York-based Lee – who has two children with Jane, his wife of 33 years – has lived in the US since 1980, arriving from his native Taiwan to study drama at the University of Illinois and film production at NYU’s Film School.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Yet Lee has frequently returned to Asia, making films like the breathtaking martial arts drama Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and Life of Pi (which garnered him a second Best Director Oscar). So it’s no surprise he’s feeling tense when we meet, the day before Donald Trump’s presidential inauguration. Already, Trump has ruffled feathers by speaking to the President of Taiwan – still regarded by mainland China as a breakaway outlaw province.

The first US leader to do so since President Jimmy Carter adopted the One China policy in 1979, recognising Beijing as China’s sole government, Lee is not convinced by Trump’s new-found interest in his homeland. “I don’t think he cares about Taiwan,” he says. “He gives China a hard-time… what can they do except kick our ass? I don’t think Trump cares about Taiwan. It’s one of the bargain chips, I suppose. I don’t think he cares for us. So we’re under the pressure of two big opposing powers – so, yeah, I do worry for my countrymen.”

With his life embedded in New York, he can’t uproot and head back to Asia, though admits he’s been “brooding” on making another film back in his native continent. He’s also desperate to shoot Thrilla In Manila, a depiction of the legendary 1975 boxing match in the Philippines between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier – again using the 120fps format. With expensive visual effects and doubts over the higher frame rate, it’s been slow-going to get it financed.

Still, the idea of Lee tackling what is commonly regarded as one of the greatest boxing matches of all time is mouth-watering. “It’s high drama!” he says. “I like to treat action like drama. It’s not verbal debate but it’s a conversation physically. I think with these two, it’s the best match ever. The fighting style, body type and what they stand for, how they were brought up, what they’re about – total opposite. I could not find anything more dramatic.”

Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk opens on 10 February

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments