Jean-Pierre Jeunet on Alien Resurrection, 25 years on: ‘I think it’s kind of sexy and weird’

The cult French director talks to Tom Fordy about his 1997 reboot, why he hates the sort of movies its screenwriter Joss Whedon makes, and his uncompromising message for those who don’t like his gruesome ‘arty’ take on Alien

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Jean-Pierre Jeunet was hailed a hero in France for directing 1997’s Alien Resurrection – the divisive (if misunderstood) fourth Alien film. “It was like I’d won the World Cup alone,” says Jeunet, who also directed the human butchery black comedy Delicatessen and later Amelie. “I had five stars on every magazine. Even I thought, man, it’s too much! The script is not so good... it’s a little bit stupid!”

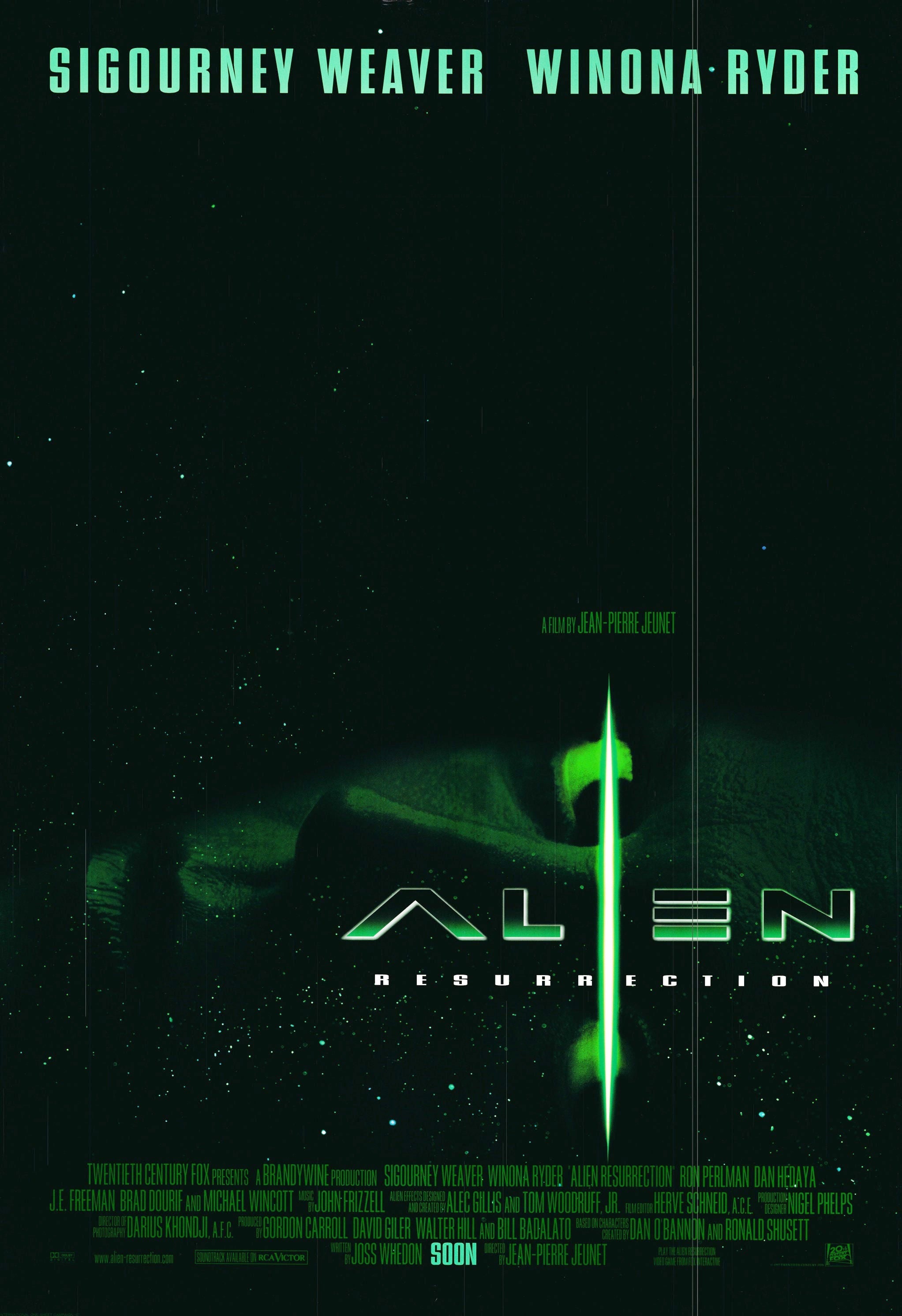

Alien Resurrection, which premiered on 6 November 1997, was less celebrated elsewhere (“The American people hate it!” laughs Jeunet) and remains shorthand for the series’ critically dubious crash into franchise fodder – a comically dark space romp in which Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley is reborn as a part-alien superwoman and almost smooches with a human-alien hybrid, the much-ridiculed “Newborn”, which also happens to be her grandchild.

Alien Resurrection was a tough gig from the start. At the end of 1992’s Alien 3 – a troubled production and the true worst Alien film – Ripley was most definitely dead, chest burst open by a baby alien queen as she also hurled herself into a giant inferno. Just in case there were any doubts. But 20th Century Fox wanted another sequel. Lt Ellen Ripley and the aliens would have to be, well, resurrected. Sigourney Weaver was “frankly stunned” at the prospect. Speaking in a making-of documentary, Weaver described how she had wanted to kill Ripley in Alien 3 to “liberate” the series from her character. She also wanted to bail on the series before the rumoured Alien vs Predator became a reality. It “sounded awful”, said Weaver. She was not wrong.

Walter Hill and David Giler – producers of the original Alien and series guardians – also opposed a fourth film. “We tried to stop them from making it,” said Giler, speaking on the same documentary. “They developed the script on their own.” Writing duties fell to then pop-culture wunderkind Joss Whedon, who was charged with figuring out how to bring Ripley back from the dead.

The story is set 200 years after Alien 3. In deep space, military scientists have cloned Ripley, using blood samples from when she was impregnated by the creature – so they can extract the baby queen and experiment with its offspring. Will they never learn? The Ripley clone – Ripley 8 – is alien-like: super strong, acid-blooded, and good at sniffing out alien stuff (not to mention being inexplicably good at basketball).

When the aliens – xenomorphs, to use the proper parlance – inevitably escape, the new hard-as-nails Ripley teams up with a band of mercenaries, including a space pirate played by Ron Perlman, a paraplegic mechanic played by Jeunet regular Dominique Pinon, and a humanist robot played by Winona Ryder. They have to escape the ship and stop it from reaching Earth. Weaver was enticed by the idea of Ripley’s potential allegiance to the aliens.

David Fincher called me and said, ‘Give up! Go back to Paris!’

The history of Alien is like an asteroid field of unproduced, alternative sequels – from the infamous monks vs aliens version of Alien 3 to Neill Blomkamp’s scrapped Alien 5. Alien Resurrection might have been different, too. The Buffy creator wrote five different endings, each change dictated by Fox’s budget-tightening.

Whedon fought to set the film’s finale on Earth. It is the Alien series’ ultimate dramatic question: what would happen if xenomorphs came to Earth? “The reason people are here is we’re going to do the thing we’ve never done,” Whedon argued. “We’re gonna go to Earth.” The studio, however, wanted to spend the money elsewhere.

The studio first approached Danny Boyle – fresh from the grime and skag of Trainspotting – as well as Peter Jackson (best known at the time for Braindead and Heavenly Creatures) and The Usual Suspects’ director Bryan Singer. Twenty-five years on, Jean-Pierre Jeunet still feels leftfield – a visually fantastical, cult favourite director. His most recent film had been the 1995 off-kilter fantasy, The City of Lost Children. Jeunet was writing his sweet-as-pie smash hit Amelie – about as un-alieny as it gets – when he got the call for Alien Resurrection.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

“I didn’t want to make a big Hollywood movie but it was interesting to go to the meeting,” recalls Jeunet, speaking from Paris. “I said, ‘Why do you want to hire me when there are so many good directors? Leave me alone, leave me alone!’” But the studio was excited by the fact he was not a Hollywood-style director. “They hired me. I was so pissed off!”

Jeunet flew out to meet Sigourney Weaver. He jokes that he would have hijacked the plane if he could – a drastic means of escaping the film. But Jeunet found support from Weaver, whom he calls his “accomplice”. When Jeunet suggested switching some of Whedon’s generic action for something “arty”, Sigourney replied: “You are my hero!”

“This is a bad word in the USA,” laughs Jeunet, mimicking the response. “Oh my god, it’s arty!”

Jeunet received a warning about the dangers of Alien: a call from Alien 3 director David Fincher. “When I arrived, David called me and said, ‘Give up! Go back to Paris! Alien 3 was a nightmare!’” laughs Jeunet. But the studio was supportive. Jeunet was able to bring his own French crew onboard, rewrite scenes, and spend two months storyboarding. “I had almost total freedom,” says Jeunet. “Can you believe it? Today it wouldn’t be possible.”

Jeunet’s major battle was keeping the cost down. “Every day you have some producer biting your legs, saying, ‘You have to go faster!’” says Jeunet. But Weaver reassured Jeunet: “Don’t worry about the money. What you do will be on the print for eternity.”

Within the parameters of grubby, rusted-up science-fiction, the Alien franchise is a jaunt through genres – from claustrophobic horror to gun-heavy Eighties action and back again – but the director was more interested in making a “Jean-Pierre Jeunet movie”. Alien Resurrection is the most obviously commercial of the first four films – coming from a period when studios were churning out proven-commodity sequels as standard blockbusters. Certainly, Alien Resurrection is full of clunky, generic action dialogue (“Real nice party, ain’t it!” quips Ron Perlman, after one intense shootout) and is snared within the sequel-by-committee formula. But it’s also a visual, inventive oddity, like a hyper-non-reality – skewed, industrial and occasionally grotesque. And slicked with embryonic goop.

Joss Whedon is very good at making films for American geeks – something for morons

Sharp moments include a captive xenomorph killing another, thus using its acid blood to escape (clever girl, as they’d say in the similarly milked Jurassic Park franchise); and when one impregnated victim uses the chest-burster as a weapon – with it bursting from his own body and through the head of a villain like a shotgun blast. Elsewhere, Ripley discovers a lab filled with botched Ripley clones – gross deformations begging to be killed. It is – in the best possible way – horrible. In one of Jeunet’s favourite scenes, the military commander played by Dan Hedaya is killed – but survives the attack long enough to pick out a part of his own brain. “Maybe it’s too much?” laughs Jeunet. The studio wanted to remove the scene, but it played brilliantly at a Las Vegas test screening. “Everyone laughed and said it was their favourite scene,” says Jeunet.

Jeunet had intended to re-enlist the original xenomorph designer, HR Giger, though the studio refused – apparently unhappy with the Swiss artist’s contributions to Alien 3. Instead, Jeunet bought Giger’s books and plastered pages of his surrealist, sexually charged work across the production design offices. Giger’s influence can be seen, particularly when Ripley is caught in the alien nest – a slithering, slimy mass of biomechanical extremities.

The actual xenomorphs got a slight upgrade, with special effects maestros and Alien veterans Tom Woodruff Jr and Alec Gillis tweaking the design. For the film’s most inspired action scene – a thumping underwater chase with swimming xenomorphs – the monsters were equipped with paddle-like tails. For Nineties kids who collected the animal-themed Aliens action figures – Gorilla Alien! Snake Alien! Killer Crab Alien! – the sight of swimming xenomorphs was indeed exciting. Being underwater, they just about get away with shonky late Nineties CGI.

A fundamental problem for Alien Resurrection is its xenomorphs have now lost the power to shock, having come out of the shadows and been put on display for several films. “For me the only interesting Alien was the first one,” says Jeunet. “It’s a f***ing masterpiece. I love it. We don’t really see the alien.”

In Alien Resurrection, the xenomorphs are zoo animals – held captive and toyed with by a destined-to-have-his-brains-bitten-out scientist (played by the voice of Chucky, Brad Dourif). Jeunet, however, didn’t see the physical creature effects until they were fully built and ready for action. He remembers some trepidation when he saw the Newborn creature for the first time. “I was a little bit concerned,” he says. “I thought we might have some problems.”

In the story, the Newborn is a human-xenomorph crossbreed – born from the Ripley-gestated alien queen. Rather than coming from an alien egg, it’s born from a newly evolved alien uterus. It’s essentially the progeny of Ripley herself. In Joss Whedon’s drafts, the Newborn was “an alien, to be sure”, with spider-like legs, pulsing red veins, and pincers emerging from its head. Jeunet wanted the Newborn to be more human – even suggesting it should have Ripley’s face at one point

The Newborn was huge – a technically impressive but unwieldy animatronic. It’s undeniably ludicrous, with a skull-like head, wibbly nose, human gnashers and sad eyes. “It’s like King Kong!” laughs Jeunet. With the Newborn recognising Ripley as its sort-of mother, things get alarmingly Freudian. “I think it’s kind of sexy and weird,” says Jeunet. “They almost make love. It was very disturbing to American people. You know how they are puritan.” The Newborn originally had both male and female genitals, which had to be removed digitally. “Even for a Frenchman it is too much,” Jeunet told his SFX team about the alien-esque bits.

As ludicrous as it looks, the Newborn meets a tragic, graphic end – turned inside-out as it’s sucked through a hole in the spaceship window. It’s an obscene concept: a rejected baby, screaming for its mother, having its guts pulled out backwards.

In a 2005 interview, Whedon disassociated himself from the Newborn. “I don’t remember writing, ‘A withered, granny-lookin’ Pumpkinhead-kinda-thing makes out with Ripley’,” he noted. “Pretty sure that stage direction never existed in any of my drafts.” In another interview that same year, Whedon put the boot in further. “It was mostly a matter of doing everything wrong,” he said about the finished film. “They said the lines... mostly... but they said them all wrong. And they cast it wrong. And they designed it wrong. And they scored it wrong. They did everything wrong that they could possibly do.” He added: “It wasn’t so much that they’d changed the script – it’s that they just executed it in such a ghastly fashion as to render it almost unwatchable.”

“I know Joss Whedon said some bad things about me,” says Jeunet. “I don’t care. I know if Joss Whedon had made the film himself, it probably would have been a big success. He’s very good at making films for American geeks – something for morons. Because he’s very good at making Marvel films. I hate this kind of movie. It’s so silly, so stupid.” About the changes he made to Whedon’s script, Jeunet jokes: “Too bad, Joss Whedon!”

Alien Resurrection was made from a reported budget of $75m. It took $48m at the US box office. “Not a disaster but almost!” says Jeunet. The film fared better worldwide, taking $161m in total. Reviews were muddled. The Independent’s write-up was overwhelmingly positive, calling it “the first [Alien] to really challenge the codes of its chosen genre” and arguing “there’s something primal and unsettling at the heart of the movie that goes beyond simple frights”. The New York Times said it was the “most freakish and macabre to date” (a sort of compliment), though it didn’t flatter Weaver’s Ripley: “The filmmaker’s ghoulishly fecund imagination makes this tale so murky that even the screen’s toughest woman warrior remains largely stuck in the mud.” The LA Times likened Alien Resurrection to its doomed scientists and their xenomorph experiments: “The mindless pursuit of misguided self-interest.”

HR Giger, however, was a fan. “I met him in France,” says Jeunet. “We had an appointment in a little hotel, sat on the edge of the bed – it was very funny.” The general mess of Alien 3 stained the series, though it’s easier to disassociate Alien Resurrection from the Alien canon. Alien Resurrection is often pegged wrongly: less a sequel than it is a comic book-like “what if?” – a standalone adventure from an alternative Alien-verse, one that imagines what could happen in the more excessive corners of Alien lore.

Alien has been weirdly unsure of itself ever since – a handful of unproduced sequels, dreary Alien vs Predator films, and mind-bogglingly poor Ridley Scott prequels, Prometheus and Alien: Covenant – as if the studio doesn’t know which universe the franchise belongs in anymore. A Disney Plus series is now set to land in 2023.

“People said why make another sequel?” recalls Jeunet. “Probably they were right.” Jeunet recently watched a 35mm print of Alien Resurrection. “I was a little bit concerned to watch my film – maybe I won’t like it?” he says. “No, it was great! I have a lot of shots that I love. For the people who don’t like it, I can say, ‘f*** you!’”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments