Alex Garland's 'Ex Machina': is true artificial intelligence sci-fi or sci-fact?

The former literary rock star's brilliant directorial debut explores the development of artificial consciousness - a subject which is more topical than ever

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference."Tough crowd …. There were some real heavyweights there, a lot of people a lot smarter than me. I was pretty terrified." So says Alex Garland, when I meet him the morning after the screening of his directorial debut, Ex Machina, to an audience of scientists. The reason for their presence? The high-concept thriller deals with that most topical of scientific topics, artificial intelligence, via the tale of a beautiful machine, Ava, believed by its creator to be the first truly human-like robot.

As if proving the film’s currency, after the screening Demis Hassabis, founder of British AI company DeepMind Technologies, approached Garland and suggested they go out to dinner; last year, DeepMind was bought by Google, becoming its largest-ever European acquisition. “This guy is actively trying to develop artificial consciousness,” Garland says, evidently impressed, “and Google have just spent £242 million to be part of it”. Ex Machina cleaves to this reality: the film’s inventor figure is Oscar Isaac’s Nathan, CEO of “Bluebook”, the world’s largest search engine.

If Garland sounds a little cowed by his new friends, then that belies his blossoming reputation as one of cinema’s foremost creators of science fiction. The 44-year-old Londoner became a literary rock star in the Nineties with his gap-year thriller The Beach. However, after retiring from literature with overwhelming writer’s block, he found a second wind in screenwriting. An obsessive JG Ballard fan, he has rebuilt his name penning dystopian fictions, from Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later and Sunshine to the adaptation of Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go and the Judge Dredd reboot Dredd.

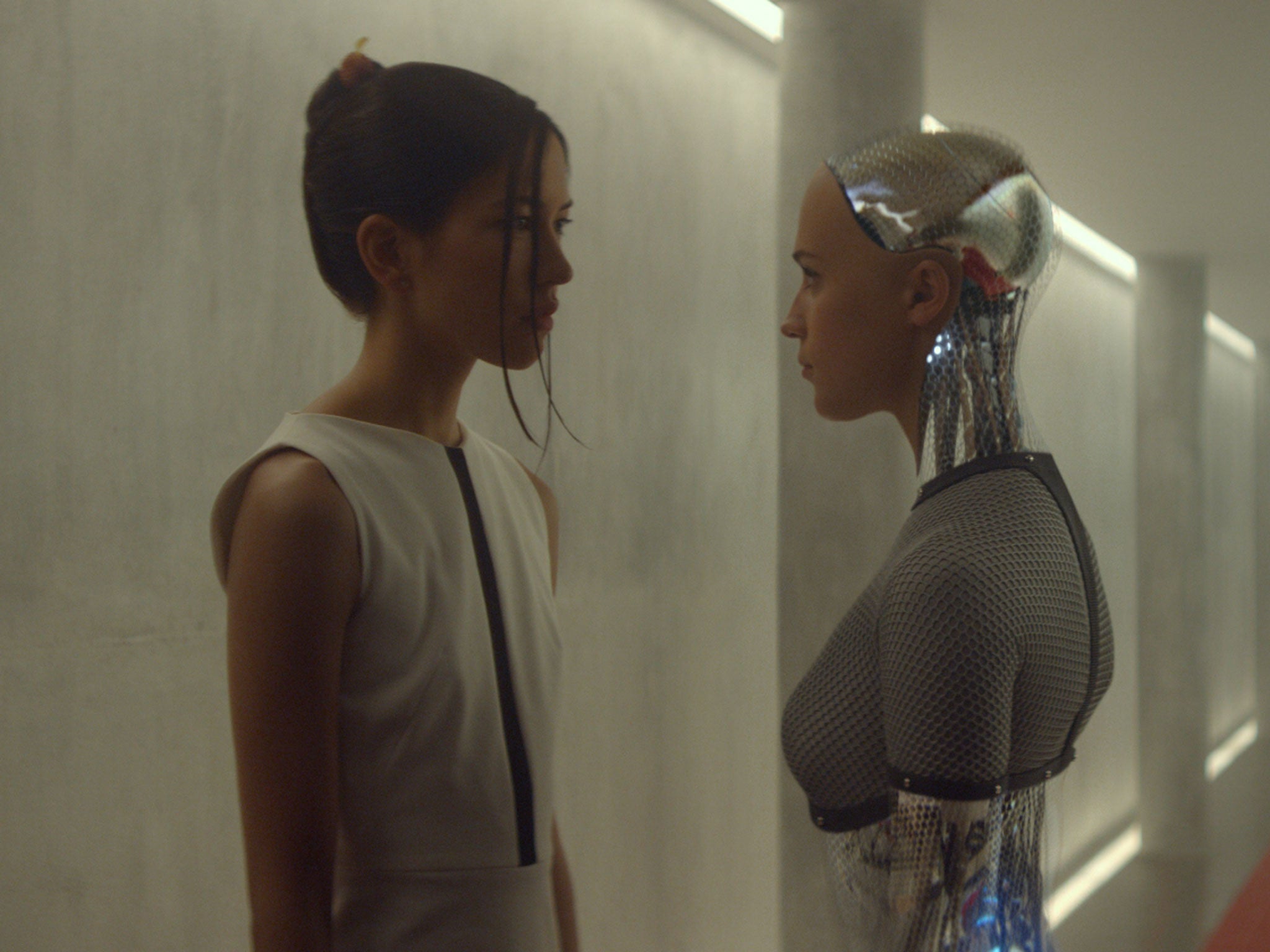

And now comes Ex Machina. Set in one location with just three speaking parts, its premise is based on the Turing Test, the method devised by the British mathematician and codebreaker Alan Turing to determine whether a machine might be experiencing a sense of consciousness comparable to our own. Isaac’s Nathan applies the test by introducing his feminine robotic creation, Ava (Alicia Vikander), to an employee of his (Domhnall Gleeson) and setting up a series of meetings between them. Is she still a machine, we wonder? Or are we witnessing something as alive and self-aware as any human?

The film plays with the idea of “the singularity”, a term coined by Hassabis’ new boss and Google’s Director of Engineering, Ray Kurzweil, to refer to the moment when humans and machines will “converge”. Kurzweil has predicted this will happen within as little as 15 years. Garland, however, expects a longer timetable before we see an AI like Ava. “My children’s lifetime, I expect,” he says when pressed. “But we are approaching a point where machines will be willing to say to us: ‘Please don’t switch me off…’ They’ll have the capacity to want something, to feel things.”

This view is shared by Ex Machina’s scientific advisors: Murray Shanahan, a professor in cognitive robotics at Imperial College, whose writings form the basis for the film’s logic, and geneticist and science broadcaster Adam Rutherford. “The robotics side of things – Ava’s body – we can get to in 10 or 15 years I think,” says Shanahan. “But Ava’s consciousness – we need a couple of conceptual breakthroughs before we get there. But in a basement of some research institute somewhere, it’s possible that these breakthroughs are taking place.” In the film, Ava’s brain is made from a sort of “structured gel”, into which all the data from every use of the world’s biggest search engine is fed. It’s a solution that feels especially convincing in the light of the Snowden revelations that search engines such as Google are capable of storing, and then exploiting, every thought and feeling we communicate through our devices.

If popular culture is our guide, then the development of conscious machines should terrify us. Cinema’s prophesies about AI range from the fretful and anxious to the outright apocalyptic: see the “time to die” replicants in Blade Runner, Skynet’s hell-bent destruction of mankind in the Terminator franchise, and, more recently, the emotional turmoil of falling for an operating system in Spike Jonze’s Her. Again and again, our organic wet-matter is celebrated over the cold hardware of the “conscious” machines trying to encroach on our turf.

In the effort to vilify robotics, Hollywood has friends in high places. During a lecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the tech pioneer Elon Musk compared the development of AI to “summoning the demon”. Meanwhile Professor Stephen Hawking recently told the BBC: “The development of full artificial intelligence could spell the end of the human race. It would take off on its own, and re-design itself at an ever-increasing rate. Humans, who are limited by slow biological evolution, couldn’t compete, and would be superseded.”

It would spoil Ex Machina to say more about its plot but Garland, unusually for a filmmaker, fundamentally disagrees with the AI scare-mongering. “I think [it] is a good thing, and I want it to happen,” he says. What about the moral implications of creating something that doesn’t age like us, and will have an analytical power far beyond our capabilities, I venture. “I don’t think there’s anything inherently bad about creating a conscious machine,” he says, “because we create new consciousness routinely in the propagation of our species – we have children. The ethical implications of creating a conscious machine are broadly similar to the ethical implications of creating a child.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Rutherford, too, dismisses Hawking’s warnings: “I don’t think he knows what he’s talking about,” he says. “We’re so informed by the dystopic visions we see in our culture: computers so advanced they no longer need us [and so on]. But if we birth a machine with our consciousness, does that not mean we should [allow it] the same rights we [allow ] ourselves? I don’t buy the idea that we’ll suddenly have to bow to our computer overlords.”

Why, does Garland think, the idea of AI scares people so much? “I think we’re more like processing machines than we want to think we are,” he says. “It disturbs people to think of their emotional connections in terms of electrochemical responses.”

“It’s easy to be premature and alarmist about these artificial creatures,” says Shanahan. “We should be careful. I think there needs to be a debate about them; we’re talking about a completely unregulated part of our society. Do I want governments to be in possession of these creatures, or private companies and individuals? I don’t know. But I am, overall, excited about them.”

“We can’t ignore this, but, in the same way, we can’t be knee-jerk and fear-mongering about it,” says Rutherford. “Google and the big tech companies are currently going through a serious land grab of AI start-ups, and it’s certainly aggressive. I wonder sometimes what they’re up to. We need to talk about it meaningfully in a democracy.”

“One day the AIs will look back on us the same way we look at fossil skeletons on the plains of Africa,” says Ava’s creator in Ex Machina. “Upright apes, ready for extinction.” Maybe that’s why we fear AI, because it makes us reflect on who we really are: flesh and blood, and much more basic than we like to believe.

‘Ex Machina’ is released in cinemas on 23 Jan

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments