A Serious Man at 10: How the Coen brothers made the most intimate and puzzling film of their careers

A decade after its release, ‘A Serious Man’ remains the brothers’ ultimate articulation of their world view. But what that view actually encompasses remains a brilliant mystery, writes Ed Power

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Every Coen brothers movie is a mystery of one kind or another. But none is more mysterious than A Serious Man, which was released in the UK 10 years ago today. Quasi-autobiographical, searingly spiritual and giddily opaque, it remains one of cinema’s ultimate puzzle boxes.

It is one of those films that stays unknowable no matter how much of its dialogue you are able to quote by heart. You can sit through it over and over – many Coen diehards will consider it the ultimate re-watch in the sibling writer/directors’ oeuvre – but it never coughs up its secrets. What lingers is the unsettling imagery: that final, Wizard of Oz-evoking shot of a tornado bearing down on a school, in particular. The only thing worse than not understanding A Serious Man, one suspects, is to grasp it fully.

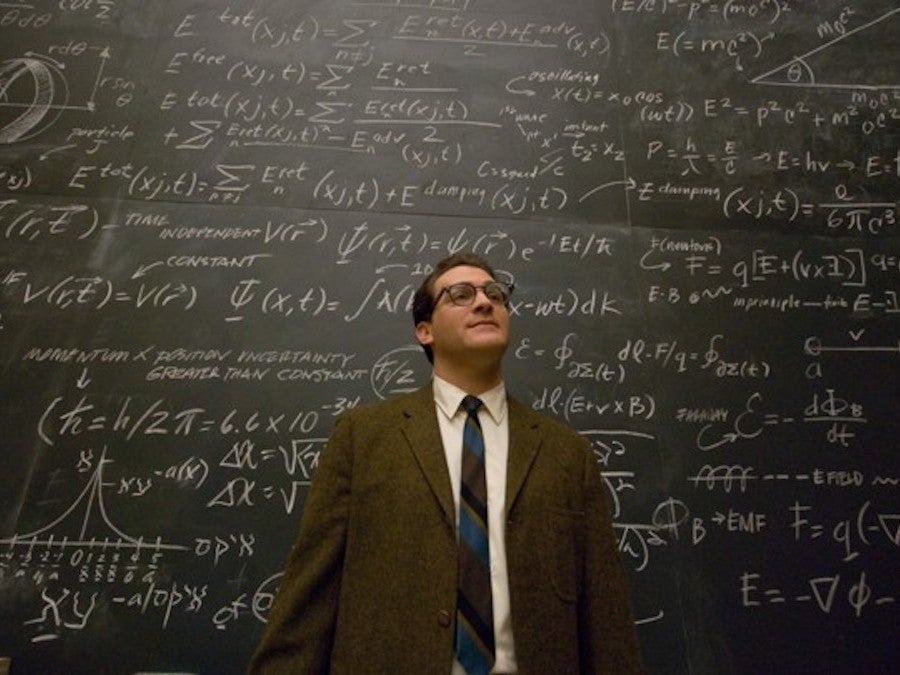

Yet on the surface it is all so straightforward. Our hero is a humble Jewish physics professor (Michael Stuhlbarg) in late-Sixties Minnesota struggling through the worst several months of his life. Larry Gopnik’s wife wants to shack up with a creepily amiable romantic rival; a F-grade student and his father are blackmailing him. And someone is whispering poisonous innuendo into the ear of the committee deciding whether or not to grant him tenure.

Such banalities are mere window dressing, though, in a character study that poses stark questions about life, willpower and what it truly means to be free. It’s deeply funny too, in that classic deadpan Joel and Ethan style. But the jokes are even darker than usual. Their Oscar-winning predecessor by one, No Country For Old Men, feel optimistic by comparison.

There is a Coen brothers movie for every season. They’ve given us apocalyptic noir (the aforementioned Cormac McCarthy adaptation), art-house vaudeville (O Brother, Where Art Thou?, The Hudsucker Proxy) and stylish auteur cinema (Barton Fink).

But there is another, less heralded side to their filmmaking. Beyond the quirkiness, there often lurks a whimsical nihilism. It’s in 1990 gumshoe tragedy Miller’s Crossing and in The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, the western anthology they made last year for Netflix.

A Serious Man might be the ultimate articulation of this world view. In having Larry’s world fall to pieces before him, it seems to argue that we are all, to one extent or another, doomed. The best way of coping is to laugh or cry – that choice being the closest thing to free will in our misbegotten lives.

Yet it is more than a howl into the dark. A Serious Man is also their sweetest and most intimate project: one of those contradictions of which you know the brothers are secretly proud. Their childhood was not unlike that of Larry’s (selfish, whining and dysfunctional) children. They grew up in the Lynchian banality of Saint Louis Park Minnesota, the same sprawling exurbia where A Serious Man unfolds (one of the biggest obstacles was locating a suburb identical to the one from their childhoods). Just like Larry, their father was a professor at the University of Minnesota, albeit of economics rather than mathematics (and his wife did not leave him for a velvet-tongued oaf).

The Jewishness in which the film is suffused, moreover, was the backdrop to their upbringing. And as a final flourish, every kid on screen is named after one of their school friends. It is a strange sort of tribute considering A Serious Man concludes with them all about to perish in the tornado.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

“With A Serious Man, for a long time we wanted to make a short film about a bar mitzvah boy who goes to see an aged rabbi,” Ethan told Esquire magazine in 2009. “We based the rabbi on one we knew when we were growing up – a sage, a Yoda who didn’t say much but had great charisma.”

Yet for all the misery and mystery, the film is tremendously compelling to watch. A Serious Man puts us in the position of actively relishing the downfall of Larry, someone so inoffensive it feels almost offensive. Early on wife Judith (Minnesota-based actress Sari Lennik) tells him she wants a “get” – the Jewish equivalent of a marriage annulment. He sits there shrugging, unable to express anger or anything beyond vague befuddlement. She adds that she intends to be with the more “serious” Sy. Larry is such a sap that even his own movie is named after someone else.

Sy is a friend of the family to whom she has “become close” since his own wife died. As portrayed by Fred Melamed, he is a sort of teddy-bear sociopath. “Ethan told me that Sy is ‘smoothly free of self-doubt’, and that they knew someone like that growing up,” said Melamed, cast after sticking in the memories of the Coens following his audition a decade previously for Barton Fink.

“Sy is one of those people who, throughout history, have done the most outrageous things and really earnestly believed that they were doing what was best for everybody; because they don’t have the doubt mechanism in place like normal people do, they destroy people.”

Marital strife is only the start of Larry’s problems. Son Danny (Aaron Wolff) owes $20 to his drug dealer at school; daughter Sarah (Jessica McManus) is saving for a nose job. A redneck neighbour is intruding on the Gopniks’ garden and clearly looking for an excuse to go crazy.

Larry’s sad-sack brother Arthur (Richard Kind) is, meanwhile, crashing at the house and toiling over a “probability map of the universe” (which turns out accurate). And, at work, a Korean student is trying to bribe him to give a pass grade, and he is bombarded with unreturned calls from a mysterious stranger. Swirling in the background is the Jefferson Airplane song “Somebody to Love”, its lyrics popping up in bizarre situations (such as when Danny is meeting the rabbi at his bar mitzvah, or when Larry dreams of becoming intimate with a sultry neighbour).

As has been the case with the Coens since the failure of their one and only big-budget feature, 1994’s Paul Newman-Tim Robbins two-hander The Hudsucker Proxy, A Serious Man was assembled on a shoe-string (just $7m). It turned a profit, earning $31m at the box office. And it was favourably reviewed. “Funny, droll, and anxiety producing, just like daily life in many Jewish families,” said The Atlantic. “A seriously funny film about an angst-ridden Jewish professor seeking the answers to life’s questions and getting a metaphysical pie in the face,” agreed the Los Angeles Times. Among the few dissenting voices was The Independent, which stated, “Comedy, even tragicomedy, should not feel like such hard work”.

One reading of A Serious Man is that it is a retelling of the Book of Job. There, God tests a “blameless” and “upright” individual by sending wrack and ruin his way. Job eventually cracks, cursing God. But God tells him that it is not for a mere man to question the ways of the divine.

The difference is the Book of Job has a happy ending. God relents and restores his loyal servant’s wealth and prominence. No such luck befalls hapless Larry. Are the Coens suggesting God is even crueller than depicted in the Old Testament? And then wrapping that message up in a sentimental glance back at their Sixties childhoods?

“I’ve done nothing,” is Larry’s refrain when something bad happens. He is, for most of the running time, infuriatingly passive. Larry refuses to accept any responsibility for his dysfunctional marriage. When he is bribed, he just sits there gawping at the envelope. The Coens’ professor father, handed cash in similar circumstances, went immediately to his superiors. And when seeking wisdom from three rabbis, he shrugs in frustration after the third and supposedly wisest declines to see him, despite clearly having nothing better to do.

That’s a lot to mull over. And we haven’t even touched on the quantum physics. Arthur reckons he has cracked the mathematical secrets that govern time and space. At the end of a lecture, Larry, for his part, seems to sum up the Coens’ take on life. “The uncertainty principle proves we can’t ever really know what’s going on,” he declares.

The Coens elaborated on absolutely none of the above as they went out to promote A Serious Man. Through their career, they have been notoriously noncommittal when invited to analyse their work. With A Serious Man, Joel and Ethan were even more inscrutable than usual. Asked to comment on actor Richard Kind’s assertion that the project was an expression of their dark world view, they did what they always do: shrug and giggle like two undergraduates coming up from a Pringles binge. “As a world view…” said Ethan, “yyyyyyyeaaaaaah. It’s an interesting story.”

Kind was scrambling in the dark. The Coens had naturally declined to share their philosophical motivations with the actors. Stuhlbarg, a respected Broadway star cast because of his unfamiliarity to cinema audiences, recalled the tremendous attention to detail on set. But if reading between the lines was to be done, it was left it to him. “When I got the part, I wrote three and a half pages of questions,” he remembered. “They patiently answered as many as they could. Those they couldn’t they let me create my own answer.”

Nor was there any room for spontaneity or improvisation. The Coens knew what they wanted; actors’ input was not sought. “They are notorious for not doing a lot of takes,” said Stuhlbarg. “Because they edit their own movies, it makes their job easier in the editing room.”

One subject on which the Coens were especially reticent was the film’s prologue. The setting is somewhere in 19th-century central Europe. A Yiddish-speaking wife is horrified to discover her husband has welcomed into their home a dybbuk – the evil spirit of a dead person. She stabs the guest, who wanders bleeding into the street. Her husband tells her bad fortune will befall them when the body is discovered.

The Coens claimed to have written this scene first, as a way of getting into the headspace of their Jewish childhoods. Beyond that, it had no relevance to what followed, they insisted. And yet, how can it be regarded as anything other than foreshadowing? As with Larry, the couple’s downfall comes when they try to take control of their fate. The dybbuk is shivved and nothing is ever the same again.

Larry has likewise allowed life to buffet him to and fro. Finally, he puts his hand on the cosmic tiller: he accepts a bribe from his student (to pay his divorce lawyer). Immediately afterwards, his doctor calls with, it is heavily implied, a cancer diagnosis. Then the tornado hits.

In fighting back against the universe – much as Job raged against God – has Larry simply made things worse? Whether that is A Serious Man’s true message is anyone’s guess. Aside, of course, from the Coens. They know exactly what is going on. But they aren’t telling.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments