A growing number of cinemas and festival curators are returning to celluloid - and audiences are loving it

What does a resurgence of 'authentic' cinema say about our relationship with film, asks Charlie Lyne

In the age of digital projection, film is now seldom shown on film. What's more, with a growing number of movies premiering on Netflix and other online platforms, "cinema" may soon leave the cinema behind, as new technologies empower people from all over the world to access films that were previously the preserve of those who lived in the right cities or knew the right people.

Some, though, mourn what's being lost along the way. If a new film can as easily premiere on your phone screen as the silver screen, what will be left of the institutions that made film what it is today? And if a film can be watched in any number of ways, which – if any – is the right way?

Two weeks from now, a seaside hotel in Eastbourne will host a new event unlike any other on the British film calendar. The Overnight Film Festival will not showcase the latest works from leading international film-makers, nor cutting-edge art cinema from underground auteurs. Instead, festival-goers will view a selection of films already available on DVD. Unlike most festivals, Overnight won't focus on what's new or exclusive, but on what's good – at least according to the tastes of its three guest curators: actor Ariane Labed, who recently appeared in The Lobster; Emma Dabiri, a teaching fellow at London's School of Oriental and African Studies; and up-and-coming director Jenn Nkiru.

Household names they are not, but that hardly matters. "We sold out the festival with no films announced," says Overnight's founder, Sam Cuthbert. Today, anyone with an internet connection and an ounce of determination has access to more or less every film ever made, but faced with such diverse offerings, it can be tempting – at least for the casual viewer – to fall back on the easy and familiar. By contrast, Overnight promises a voyage into the unknown. This year's line-up, now fully announced, includes such little-seen titles as the 1997 Southern Gothic drama Eve's Bayou and Terence Nance's acclaimed cine love letter An Oversimplification of Her Beauty, released in the UK in 2014, but barely.

Of course, you could save yourself the cost of entry and methodically work your way through the films at home, but that would require the kind of self-discipline that's hard to marshal when you're a season behind on Orange is the New Black and haven't even started Deutschland 83. "I love having the control taken out of my hands," admits Cuthbert. "I like to disconnect and have someone else do the work for me."

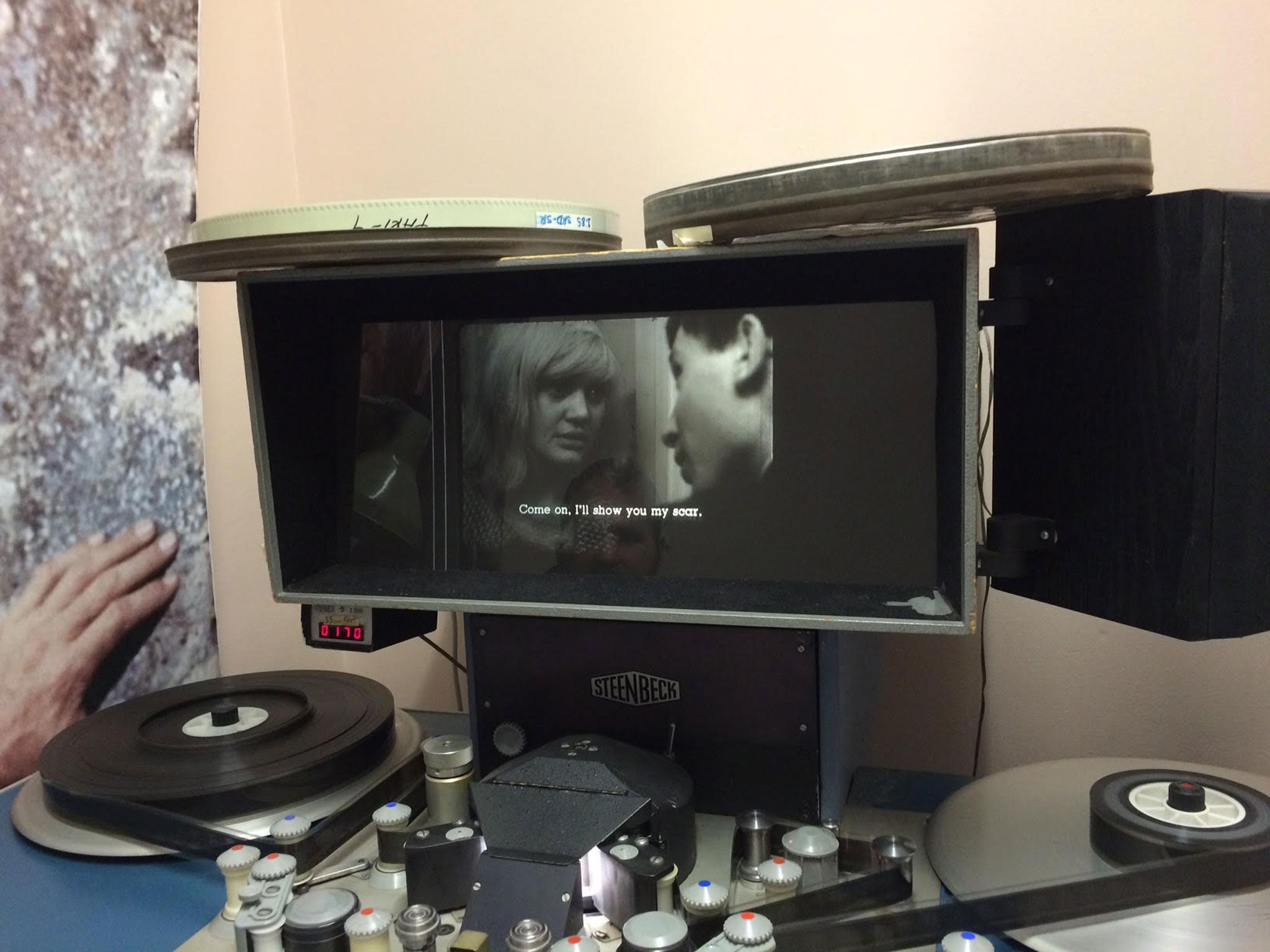

In the decades before VHS popularised the concept of watching films "on demand", every trip to the movies was an exercise in trust between an audience and a programmer, the latter hoping to win the former's approval often enough to retain their custom. Overnight is reintroducing trust into the equation, along with another key component of cinema's past: unlike Britain's fully digitised multiplexes, the festival will screen the majority of its films from 35mm prints.

Purists insist that 35mm (and its rarely screened cousin, 70mm) has a tangible quality that can't be replicated with zeroes and ones, and there's no denying the romantic connotations of celluloid. For Overnight's screenings, Cuthbert and another projectionist will stand at the back of the hotel's main hall with two vintage film projectors, changing the reels by hand.

If that sounds idyllic to you, you're not alone. An appreciation for old-school film presentation has flourished in the past few years, and not just in hipster circles. In Los Angeles, Quentin Tarantino's New Beverly Cinema has thrived by showing 35mm prints exclusively, many from the director's personal collection. Closer to home, London's beloved Prince Charles Cinema makes regular use of its 35mm projector, and last year had its 70mm capabilities reinstated after a 15-year hiatus.

The cinema's head programmer, Paul Vickery, says the decision to bring back 70mm was a simple one. "All of a sudden, everybody's interested in seeing everything on 70mm," he explains, though he adds that most audience members "don't really understand what that means". (He points me to the cinema's website, which has a lengthy FAQ page for anyone keen to learn more.) It's incredible to think that cinema's audience has become so tech-savvy in so little time. I remember attending a screening of Jaws at the Prince Charles a few years ago, at which the film was projected from a DVD (legend has it that the sole print available at the time had been so heavily mutilated by projectionists – eager to take home a souvenir frame – that it no longer featured a shark). The audience either didn't notice or didn't really care.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Clearly, times have changed. "Last year we screened Die Hard on digital and sold 100 to 150 tickets," Vickery tells me. "At Christmas we put it on 70mm and had seven screenings. That's the difference now." It's not hard to imagine who might be leading the charge to bring these formats back into fashion. Major film-makers such as JJ Abrams and Christopher Nolan regularly talk up the experience of watching film on film, while Tarantino feels so strongly about it that last month his new movie, The Hateful Eight, was treated to a 70mm roadshow release, complete with overture and intermission, at his personal request. "I'm guaranteeing, to some degree or another, that there will be 70mm film prints out there in the world, screening for people who care," enthused Tarantino in a viral video designed to promote the release. The implication was clear: if you don't care, you should.

Tarantino's gambit paid off. On the film's opening weekend, those who ventured to the Odeon Leicester Square – which had exclusive UK rights to show the film from 70mm – were met by queues that stretched around the block, despite the well-publicised leaking of the film online a week earlier. Evidently, audiences were persuaded that seeing Tarantino's film in the way he intended was worthwhile.

At the same time, fixating on the conditions of a film's release inevitably limits who gets to see the film in question. Having given special privileges to the Odeon Leicester Square, The Hateful Eight's distributor fell out with three of the UK's major cinema chains: Cineworld, Picturehouse and Curzon. As a result, people in many parts of the country were unable to see the film at all – a pragmatic reality that stood in contrast to Tarantino's idealistic intentions, and a subject on which the usually outspoken director was markedly quiet.

Ultimately, audiences will decide for themselves the right way to watch a film, and with the average US teenager visiting the cinema just six times a year, it seems tomorrow's movie-goers may be going no further than their laptops.

Until then, the question of how films are shown – and which films are shown in the first place – will remain a provocative one. Corrina Antrobus is the founder of Bechdel Test Fest, a feminist screening series that has rescued a number of films from the ignominy of a straight-to-DVD release. Last year, I attended Antrobus's packed-out screening of Gina Prince-Bythewood's Beyond the Lights, a film that earnt back twice its budget at the US box office but failed to secure a UK cinema release – perhaps, as some commentators suggested, because it featured two black actors in the lead roles.

"We saw it as a film that has cinematic qualities," says Antrobus, and so there was "an opportunity to celebrate a female director's work in the way that she intended". If accusations of a racial bias among the UK's film distributors are merited, then it was also a good way to prove the existence of an audience for films like Beyond the Lights. "There was a political element," says Antrobus, because it's understood that "if a film gets into cinemas, that's the cinemas believing there's an audience, believing that people want to see diverse stories". Politics aside, there was also the simple pleasure of getting the film on to the big screen: "Maybe it's a romantic opinion," she says, "but I still believe in cinema."

Non-accommodation tickets are still available for Overnight Film Festival (overnightfilmfestival.com), which runs from 26-28 February. 70mm films screen monthly at the Prince Charles Cinema, London WC2 (princecharlescinema.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments