Point of No Return: East German art finally gets its moment

Thirty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, art from the GDR is finally being exhibited in the biggest show of its kind with a range of diverse perspectives, writes Catherine Hickley

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A young woman and man are submerged in dry, cracked earth. Only their hands and faces are visible; they seem to be trying to pull themselves out.

That 1990 painting by Norbert Wagenbrett, called Aufbruch (“Awakening”), is part of a sweeping new exhibition staged for the 30th anniversary of the peaceful uprising that culminated in the fall of the Berlin Wall. The show, running unti 3 November at the Museum of Fine Arts in Leipzig, is just a few hundred yards from the church where activists began regularly gathering in 1989 to push for change in the stifling, authoritarian East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic, or GDR.

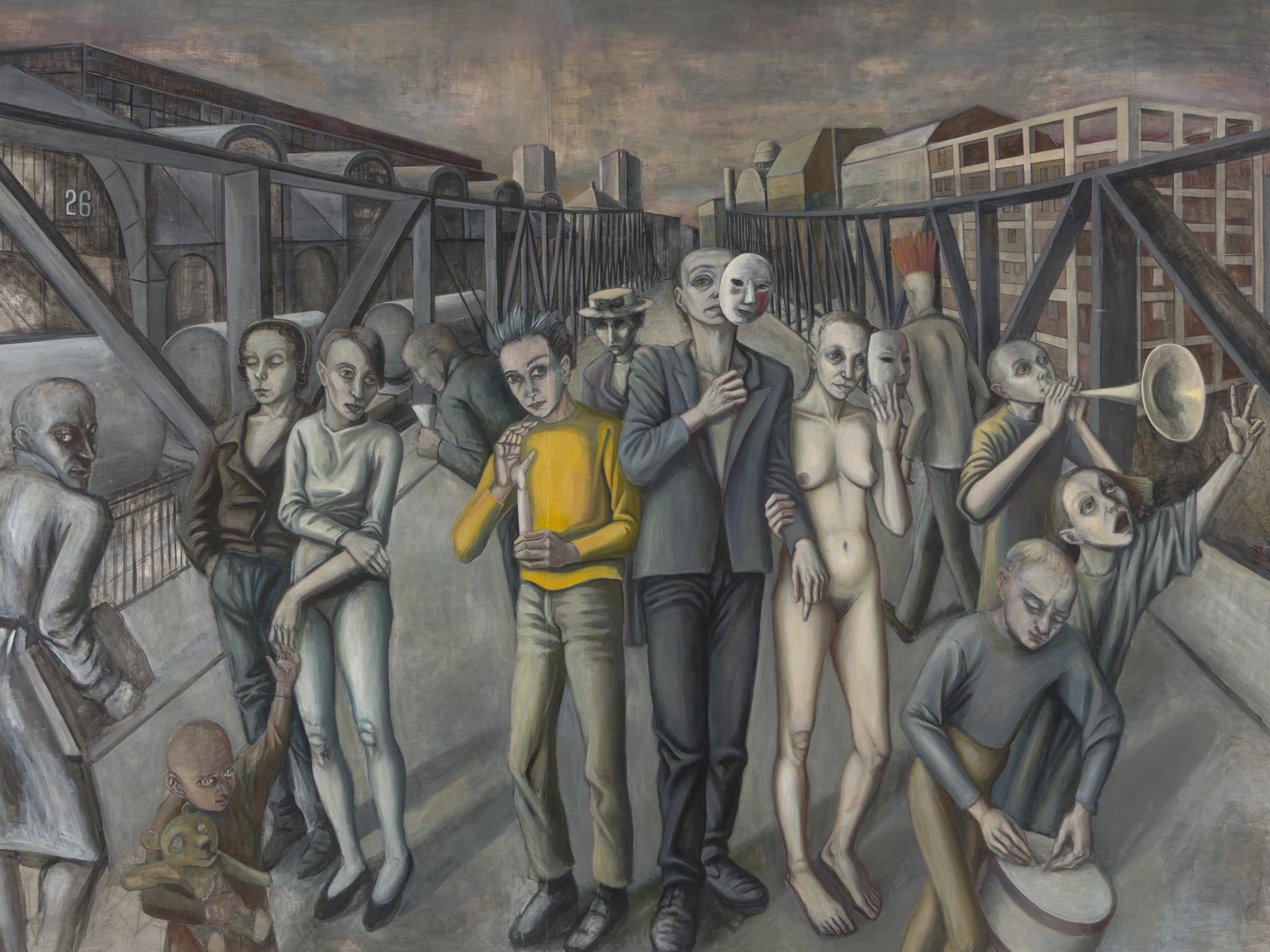

The exhibition, Point of No Return, is billed as the biggest so far of East German art, featuring 300 works by more than 100 artists, including dissidents who defied the communist regime and established figures who taught in its institutions.

The range of perspectives on the fall of the Berlin Wall is correspondingly diverse. But the mood is almost universally sombre – far removed from the fireworks and self-congratulatory speeches that usually accompany official anniversary celebrations.

Works like Wagenbrett’s Aufbruch are a reminder that what was largely perceived as a momentous, euphoric event in the west was, in East Germany, an era of great danger, anxiety and upheaval. The two young people in the earth are not experiencing a glorious rebirth; it is both perilous and painful.

After 1989, many East German state enterprises were sold to western companies and taken over (or closed down); many museums and arts institutions also got new leaders from the west. A simmering resentment at these perceived indignities persists among older East Germans – a sense that the people of a country that vanished from the map were sidelined in the process of German reunification.

Paul Kaiser, one of the curators of Point of No Return, said that “30 years after the fall of the wall, the process of categorising East German art within the pan-German context is still conflict-ridden and incomplete”. The exhibition was “a further step in synthesising the history of East German art into German art history”, he added, and in countering its “politicisation and devaluation”.

After 1989, the art of East Germany was often dismissed in the west as the product of a totalitarian regime under which artistic freedom was severely limited. In 1990, in a debate that became known as the “bilderstreit”, or “battle over pictures”, painter Georg Baselitz said in a magazine interview that there were “no artists in the GDR”. Anyone who could paint had left, he said – as both he and Gerhard Richter, now the two top-selling German artists, had done before the Berlin Wall was erected.

Kaiser prompted a rancorous revival of the debate in 2017, when he wrote a newspaper opinion piece expressing dismay that the main showcase of modern art in Dresden, a city in the former East Germany, had consigned art produced under the dictatorship to the depot. The museum’s director, Hilke Wagner, who refuted Kaiser’s claim, was inundated with hate mail.

The debate became a proxy battlefield for a host of festering East German grievances. The Dresden museum, the Albertinum, responded by staging a show of East German art in 2018, accompanied by a programme of talks and events aimed at bringing the public into the museum for open discussions.

Other institutions in the former East Germany, including the Museum of Fine Arts in Leipzig and the Moritzburg Art Museum in Halle, have picked up the baton, unearthing stores of East German art from their depots and retooling their permanent displays to raise the profile of the works.

But gaps in museum collections remain – particularly in the case of artists who were either dissidents or working under the official radar. More than 70 per cent of works on show in Point of No Return are loans, many from the artists themselves. That allows for plenty of discoveries. One room in the show is dominated by a series of melancholy large-format paintings called Passages by Doris Ziegler, a Leipzig artist whose work has rarely been exhibited.

“In 1988, we all thought the GDR would stay as it was till we die,” Ziegler said in a recent interview. “The situation was ridiculous but also threatening. The climate was grey, it was moribund. Best friends and colleagues had left, and I was constantly asking myself whether I should leave, too.”

The process of categorising East German art within the pan-German context is still conflict-ridden and incomplete

The “point of no return” referred to in the exhibition’s title is 9 November 1989, the night when crowds of East Germans breached the Berlin Wall. The crowds streaming across the border are captured in a 1989 painting by Trak Wendisch as a river of light against a lugubrious violet and black cityscape.

But the show also examines what Kaiser called “the cracks in the wall” that began developing in the early 1980s. The East German regime was among the most rigid in the eastern bloc in rejecting the avant-garde in the 1950s and 1960s, dismissing art that was abstract or expressionist as “decadent,” “formalistic”, or “revisionist”. But it began to loosen its grip on creative activity, starting in the 1970s.

“The fall of the Berlin Wall was not an instantaneous change for artists; it was the symbolic culmination of a process,” Kaiser said in an interview. “There was a momentum towards it, a processing of winning back artistic freedom.”

From the early 1980s, pockets of relatively free artistic expression began to develop in ramshackle apartment blocks in dilapidated districts of big East German cities, he said, including Neustadt in Dresden and Prenzlauer Berg in Berlin.

Many of the artworks of this era address a feeling of entrapment and desperation to escape. A 1984 work by Stefan Plenkers, Boat Cemetery, depicts a beach strewn with fragments of boats and the heads of two people with their backs turned to the viewer, as though staring out to sea longingly, but stranded because the vessels are all broken. A 1983 work by Wendisch, Man With Suitcase, shows its subject crossing a demarcation line from East to West Berlin.

Yet freedom, when it came, was not unequivocally welcomed. Perhaps one of the most unnerving works in the show is by Willi Sitte, a committed socialist and the long-serving president of East Germany’s official artists’ association.

For some, he was the epitome of a “state artist”, but in the 1960s, he fought for greater artistic independence and was put under surveillance by the Stasi, East Germany’s secret police. His 1990 work, Erdgeister (“Earth Spirits”) shows the artist upside down, his head buried in the mud. All around him are East German workers in the same position. For Sitte, the world had been turned on its head.

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments