The audacious Wordsworth who put mountaineering on the map in the 19th century

William Wordsworth’s sister Dorothy tackled Scafell Pike at a time when it was frowned upon for women to walk by themselves – let alone in the remote uplands

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scafell Pike, England’s highest mountain, is a popular place to climb, both as part of the Three Peaks Challenge and for walkers in search of the sublime Lake District scenery. But it wasn’t always this way.

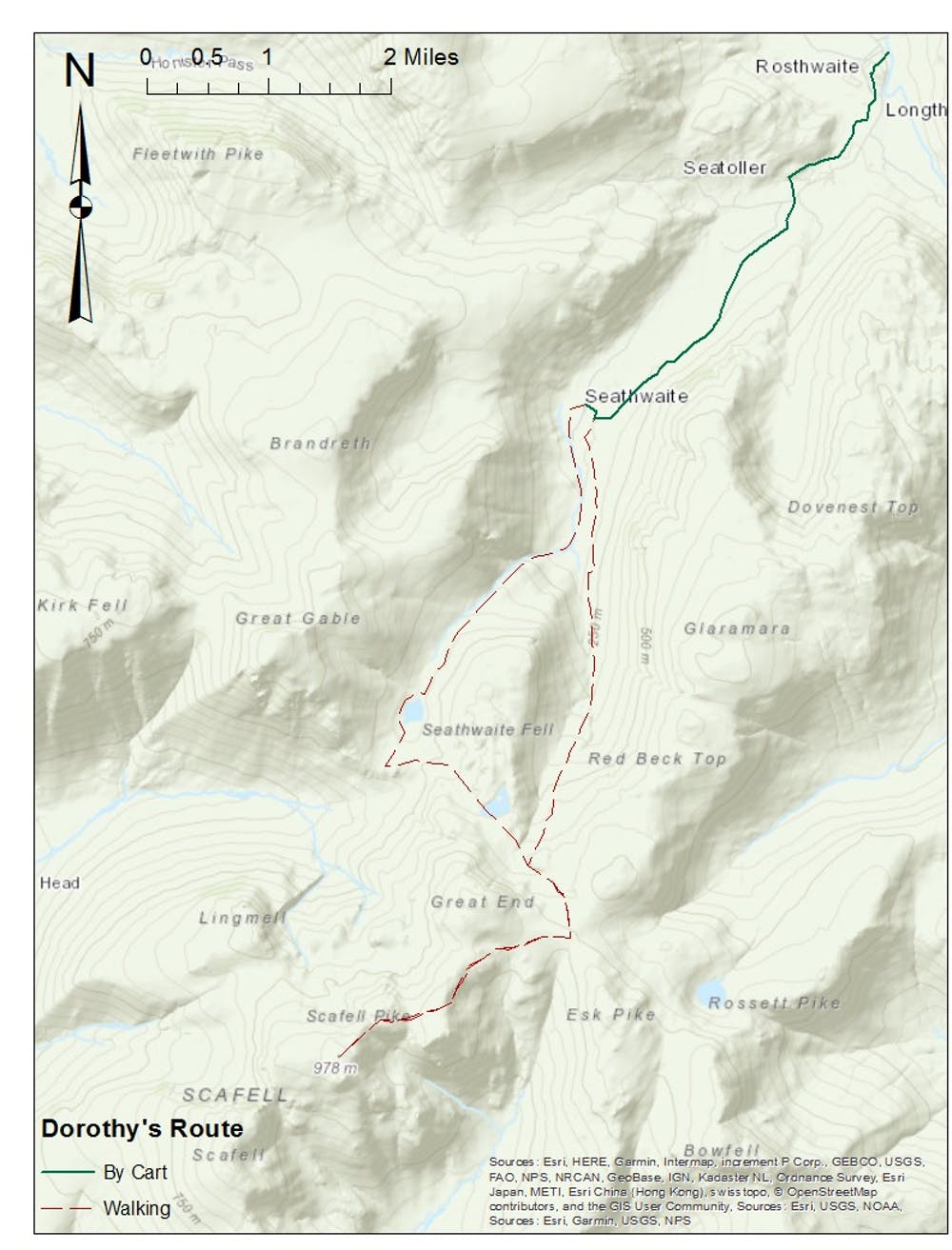

In the early 19th century – when mountaineering at all was still an unusual activity – Scafell Pike was rarely climbed. But that didn’t stop Dorothy Wordsworth and her friend Mary Barker ascending the mountain in October 1818. In an age when women walking by themselves – let alone in the remote uplands – was frowned upon, this was a daring feat.

Wordsworth is best known as the poet William Wordsworth’s sister. The siblings lived together for most of their lives, and Dorothy was an important influence over William’s verse. But she was also an important figure in her own right, and her account of climbing Scafell Pike is among the first written records of a recreational ascent of the mountain – and it’s the earliest such account to be written by a woman.

As a new exhibition reveals, Wordsworth and Barker’s climb of Scafell Pike was not simply a mountain climb, but a rebellious act that opened up mountains – and mountaineering – for successive generations of women.

Natural strength

Walking was an important part of the Wordsworths’ daily routine, but they were well aware and proud of the fact that their commitment to almost daily extensive walks was unusual. The Wordsworth siblings walked together most days for the best part of four decades – Thomas de Quincey estimated that William walked 175,000 miles over his lifetime, and Dorothy can’t have fallen far short of this figure.

In her letters, Dorothy repeatedly bragged about the speed with which she could walk – and how little fatigued she was afterwards – until her mid-fifties. In 1818, when she was 46, she boasted to the writer Sara Coleridge that she could “walk 16 miles in four hours and three quarters, with short rests between, on a blustering cold day, without having felt any fatigue”. That’s an impressive pace of a little under four miles an hour around the Lake District hills.

The climb

Climbing up Scafell Pike with Barker was perhaps Wordsworth’s most significant walking achievement. Reading the letter in which she describes this feat suggests her way of understanding the mountains went well beyond tales of sporting prowess. She saw that examining the details of a mountainside could be just as rewarding as the view from the summit.

In one moment she describes a landscape that stretches out for miles from the summit on which she stands. But at the next, when she looks down, she realises that though the summit seemed lifeless at first glance, beauty could be found clinging to the rocks:

“I ought to have described the last part of our ascent to Scaw Fell pike. There, not a blade of grass was to be seen – hardly a cushion of moss, and that was parched and brown; and only growing rarely between the huge blocks and stones which cover the summit and lie in heaps all round to a great distance, like skeletons or bones of the Earth not wanted at the creation, and here left to be covered with never-dying lichens, which the clouds and dews nourish; and adorn with colours of the most vivid and exquisite beauty, and endless in variety.” (Quoted with permission from The Wordsworth Trust.)

In focusing on these details close to hand, rather than only rhapsodising on the distant prospect, Wordsworth anticipates writers like Nan Shepherd – who is best known for her account of the Cairngorms The Living Mountain – by proposing an alternative to more familiar accounts of mountaineering exploits that emphasise a victory over a feminised Mother Nature when the climber conquers the summit. Instead, Wordsworth recognises that paying close attention reveals unexpected features even on a barren mountaintop.

Dorothy’s legacy

Wordsworth’s account of the ascent of Scafell was later included – without attribution – in William Wordsworth’s Guide through the District of the Lakes. The implication was that it was William who had undertaken the ascent. As a result, her legacy in climbing Scafell is blurred into William’s, and many of the people who followed in her footsteps were unaware that it was her they were emulating.

Despite this, her ambitious walking practices helped to establish women’s walking as an accepted habit, with many following in her footsteps. Wordsworth and countless others after her made it clear that walking and other forms of mountaineering were as much for women as for men, and in this way they helped to make the mountains more culturally accessible places for everyone to explore.

Joanna Taylor is a presidential academic fellow in digital humanities at the University of Manchester. This article first appeared on The Conversation (theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments