‘I gave. I gave. I gave’: Daniel Kaluuya on his craft and ‘Judas and the Black Messiah’

In four short years, Kaluuya has claimed a place in Hollywood among the most consequential leading men of his generation. He spoke to Reggie Ugwu about his new, award-winning film, ‘Judas and the Black Messiah’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Daniel Kaluuya sized up the room. It was the kind of Hollywood meeting room he’d been in countless times before: brightly lit, with white walls and framed posters of classic movies. It was summer, 2019, and Kaluuya had driven to the Warner Bros lot in Burbank, California, for a table reading of a film that hadn’t yet been cleared for production: Judas and the Black Messiah, a crime thriller and historical epic about the downfall of Fred Hampton, the rising star of the Black Panther Party who was murdered by police in 1969.

Seated next to Kaluuya on one side of a long conference table were his would-be co-stars, Dominique Fishback, Lakeith Stanfield and Jesse Plemons. Clustered across from them were the Warner Bros bigwigs who had the power to give the film the green light: Niija Kuykendall, executive vice president of feature production; Courtenay Valenti, president of production; and Toby Emmerich, head of the studio.

Kaluuya, who was playing Hampton, felt petrified. He figured he was only a quarter of the way into preparing for the role, his first in a film based on a historical figure. Word of whatever he did in that room, he knew, would spread throughout the building. What he didn’t know was that the stakes were even more concrete; producers of the film had arranged for the reading as part of an effort to get $1m added to its budget. A good reception could convince the studio to write the cheque.

During the second half of the hour-long reading, in a scene where Hampton gives a rousing speech to a throng of fired-up supporters, Kaluuya pushed all his chips on the table. “If I’m going to die, I’m going to die shooting,” he thought, standing up from his chair and staring out at the group. Heart pounding in his chest, he thundered the lines of a call-and-response that would later be made famous by the film’s trailer.

“I AM! A REVOLUTIONARY! I AM! A REVOLUTIONARY! I AM! A REVOLUTIONARY!”

“As soon as I heard him in speaking in Fred’s voice, I just started crying,” says Stanfield, who was playing Bill O’Neal, the FBI informant who betrays Hampton.

“Everyone else was in a screenplay reading, but he turned it into a play,” says Shaka King, the film’s director, co-writer and producer, who was seated across from Kaluuya. “There were only around 20 of us in the room, but he played it like he was performing in a theatre for 300 and had to reach the back row.”

Shortly after the table read, Warner Bros agreed to the extra $1m in financing, King says. The film went into production that autumn.

Kaluuya, who had worked hard to create and maintain the borders between himself and his character, felt them beginning to crumble

In four short years, Kaluuya, who is 32 and grew up on a housing estate in London, has claimed a place in Hollywood among the most consequential leading men of his generation. A child actor who got his start in the influential British teen drama Skins, he earned a best actor Oscar nomination for his first leading role in the United States: as the intrepid survivor of a secret race cult in the 2017 smash Get Out.

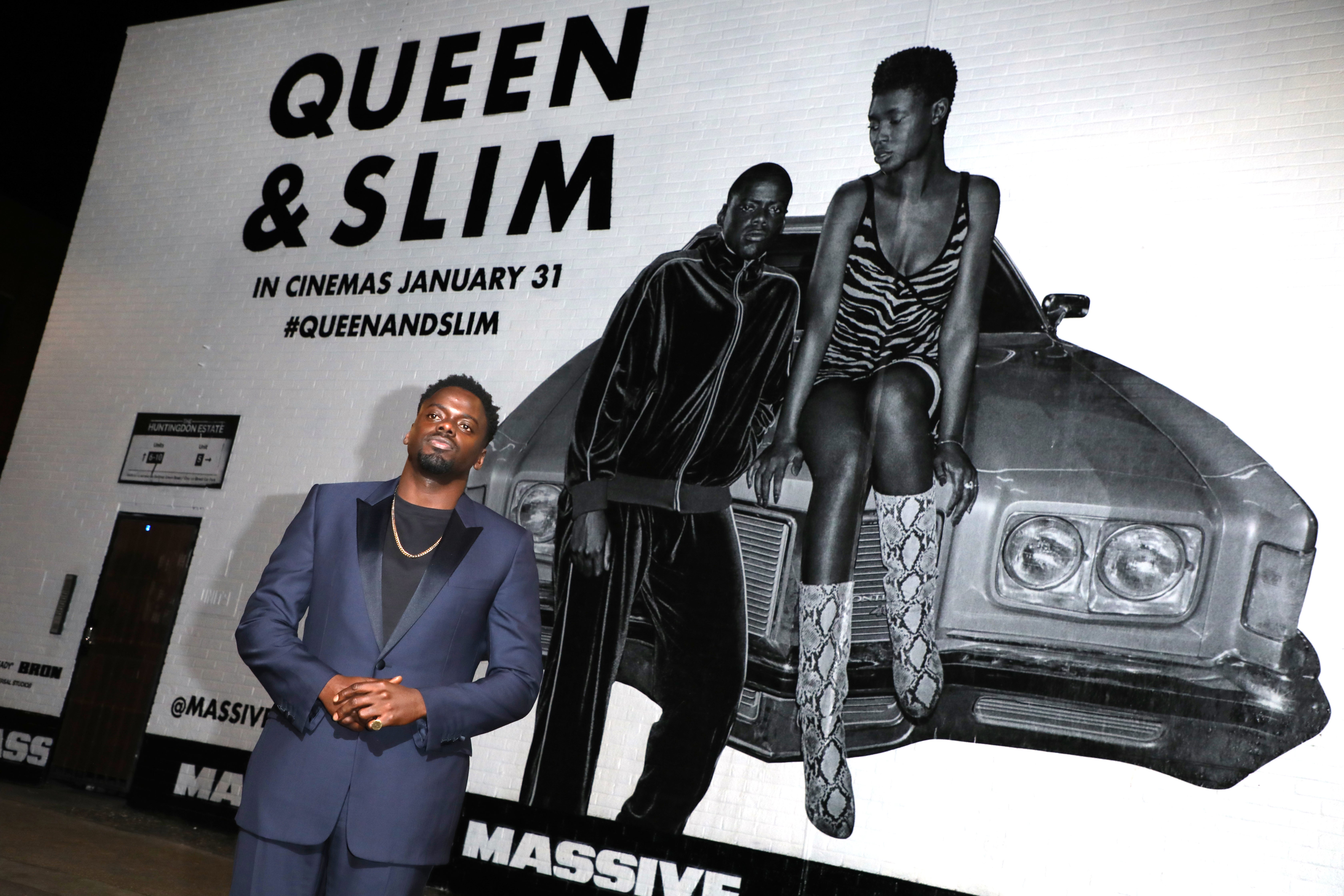

Kaluuya followed that breakout moment with a succession of tailored and captivating performances in an eclectic range of genres. He played a conflicted warrior in Marvel’s international blockbuster Black Panther, a blood-chilling villain in the Steve McQueen thriller Widows and a charismatic love interest in the romantic getaway drama Queen & Slim. Whatever the part, Kaluuya’s bone-deep immersion pulled you a few inches closer to the screen.

With Judas and the Black Messiah, he has set a new high-water mark. The performance “takes up the burden of incarnating and exorcising both the monster of Hoover’s imagination and a martyr of the Black Power movement,” New York Times critic AO Scott wrote, adding that Kaluuya “more than meets the challenge.”

For his efforts, Kaluuya has been rewarded with a Golden Globe for best supporting actor, and presumed front-runner status in this year’s Oscar race. Getting here required him to dig deeper than ever, navigating precarious historical, physical and emotional fault lines in the process.

“People can say whatever they’re going to say about the performance, and I’ll still feel free,” Kaluuya says from Los Angeles in one of two conversations we have by video and phone call. “I gave it everything I had. I gave. I gave. I gave.”

Finding Fred Hampton

Kaluuya has a confident aura, penetrating gaze and self-described “kind African face.” To play Chris in Get Out he had to dial back his natural boisterousness, which manifests in conversation as a kind of benevolent intensity. “My essence is more Chairman Fred, energy-wise,” he says, referring to Hampton. Because he has so frequently played an American on film, his working-class London accent is initially jarring. It’s befuddling to imagine the British-born son of a Ugandan immigrant beneath the layered incarnation of Hampton that appears in Judas.

Kaluuya approached his performance from several angles at once. He steeped himself in the Panthers’ formative influences, including works by Frantz Fanon and Jomo Kenyatta; grew out his hair (“As a black person, hair is how you see yourself, how you feel about yourself and how you treat yourself”); put on a noticeable amount of bulk; and even temporarily took up smoking. (“When I see a film, I can always tell when someone smoking is a non-smoker,” Kaluuya says.)

But the trickiest element was the voice. Hampton, who was raised in Chicago by parents who moved from Louisiana during the Great Migration, was known for his sonorous, idiosyncratic intonation. To summon it, Kaluuya began with the Black Power idol’s lived experience.

He consulted with Hampton’s family – including his son, Fred Hampton Jr, and Junior’s mother, Akua Njeri (formerly Deborah Johnson) – and took a field trip to Maywood, the Chicago suburb where Hampton grew up. Kaluuya visited Hampton’s early homes, schools and speaking venues, talking with the people he met there, including students and former Panthers, about Hampton’s life and legacy.

“An accent is just an aesthetic expression of what’s going on on the inside,” Kaluuya says. “I had to understand where he was coming from spiritually, what concoction of beliefs and thinking patterns allowed this voice to happen.”

Kaluuya further refined the performance with the help of dialect coach Audrey LeCrone, as well as an opera-singing coach, who taught him how to condition his vocal cords and engage his diaphragm for the big speech scenes. By the time filming started, he felt able to deliver his lines with what felt closer to honesty than imitation.

As a teenager in London, Kaluuya learned acting at an experimental improvisational theatre, and he tries to augment his performances with a top layer of spontaneity. He wants to feel as if even scripted moments are unfolding in real time, a sense of dynamic possibility that can be transferred to the audience.

“I don’t feel like I’m entitled to anyone’s attention,” Kaluuya says. “I have to offer, or channel, or shape something that’s going to make you want to give it to me.”

Lena Waithe, who wrote and produced Queen & Slim, tells me that while filming that film’s climactic sequence, in which the fugitive main characters face a moment of truth, she thought Kaluuya seemed in touch with a higher power.

“He was in another place,” she says. “He was allowing himself to find things that aren’t on the page.”

The anniversary

The weight of history hung over every take of the Judas shoot. But Kaluuya remembers one day in particular as the hardest of his professional life.

The cast and crew were recreating the night when Chicago police officers shot a drugged Hampton dead in his sleep (O’Neal had put a barbiturate in his drink at a dinner party) on the 50th anniversary of the real-life events.

“It was a hard night for all of us,” Stanfield says. “The energy was so thick that you could feel it.”

Kaluuya, who had worked hard to create and maintain the borders between himself and his character, felt them beginning to crumble. Suddenly, he was viewing the scene not as a Black man in 1969 but as one in 2019, with a half-century of further data on the odds of survival in a white world.

His first instinct was to suppress the emotions rising inside him. “If you get too invested in your own feelings, it can start to muddle you up,” Kaluuya says. But he decided they belonged on the screen. It was the one thing he had left to give.

“That’s where the hours show up. That’s where the craft shows up,” he says. “You don’t deny that feeling; you use it, because it’s the truth.”

© The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments