Steven Isserlis/Alexander Melnikov, Wigmore Hall, London, review: They make an exceptionally fine duo

The cellist and pianist perform works by contemporary pianists Mikhail Pletnev and Evgeny Kissin, as well as scores by Shostakovich and Rachmaninoff

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

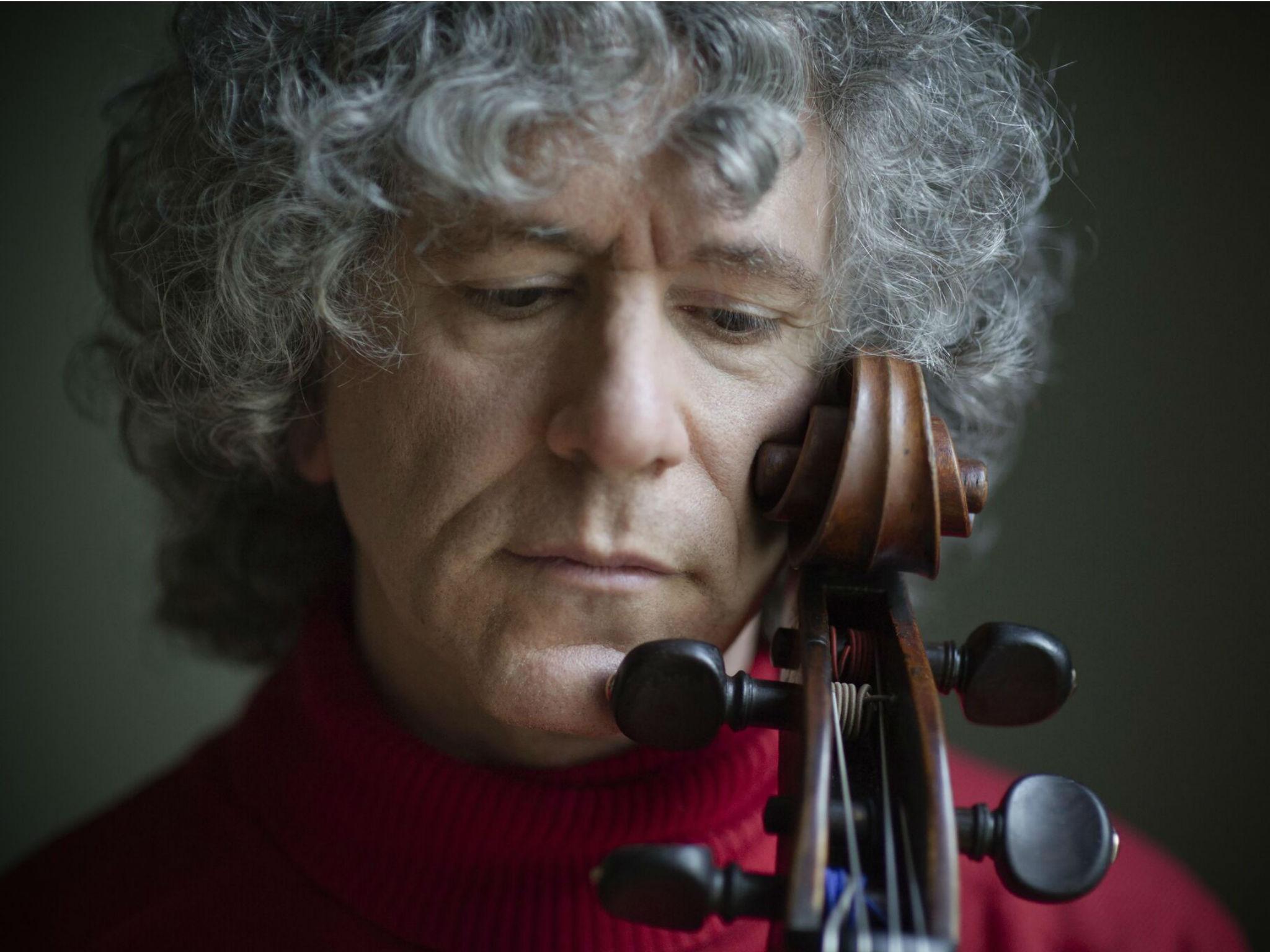

Your support makes all the difference.At first glance, Steven Isserlis and Alexander Melnikov might seem an odd couple – a mop-headed weirdo with a cello, and a priest-like presence at the piano. But both are distinguished solo recitalists, and they make an exceptionally fine duo.

They also make a point of serving up something more intriguing than the core repertoire. Their programme at the Wigmore consisted of four Russian cello sonatas, two of which showed great composers in an unfamiliar light, with the other two – which it was a safe guess nobody in the audience had heard – being by virtuoso pianists. The hall was sold out, partly thanks to these musicians’ respective followings, and partly because of the unusual fare.

All the world knows about Evgeny Kissin’s pianistic artistry, but his compositions have been growing in secret. His Sonata-Ballade for cello and piano proved a coolly intricate construction, not so much a dialogue as two parallel monologues in which one (the piano) gradually came to decorate the other; Kissin’s achievement was to make the piece feel like one single continuous thought.

Mikhail Pletnev has apparently described the final movement of his “Cello Sonata” as “an elegy for music”, and as it slowly died away, leaving a long cello melody singing in a deserted landscape, that message was clear. I assume Pletnev was indicating the death of his beloved classical tradition: the other two movements reflected his hard-edged musical imagination going at full tilt – playful, ironical, precise, and full of surprises, just like his pianism.

Shostakovich’s “Cello Sonata in D minor” was written in 1934, and reflects the composer happily at work at a time when he felt free to explore his ideas without any fear of the political consequences. The first movement’s alternation between gentle lyricism and thickening textures plus darkening moods gives way to a wild dance, a largo adumbrating some of the slow movements of his later symphonies, and a finale in which one can sense him relishing what he himself could do as both composer and pianist.

Rachmaninoff’s “Cello Sonata in G minor Opus 19” was the expected high point of this recital, addressing us out of the high Romantic tradition with the aid of that composer’s inimitable lyric gift and his glorious piano-writing. Like everything else in this programme, this seldom-played work was delivered with supreme accomplishment.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments