St Luke Passion, Cathedral, Canterbury

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

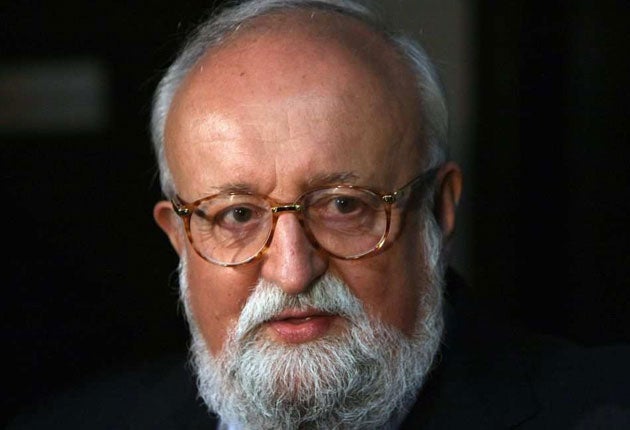

Your support makes all the difference.Half a century ago, Krzysztof Penderecki saw his St Luke Passion travel the world as an instant sensation. It was that rare phenomenon, an avant-garde work on a grand scale that surpassed its difficulties of performance and moved large audiences. Then, it mysteriously disappeared. Saturday's revival by the Sounds New festival was the first in Britain for nearly 30 years. Bringing in a ready-prepared performance by top Polish musicians with the composer conducting, it was the culmination of this year's Polish Connections theme and, with the cathedral nave packed out, destined to put a previously local festival on the national map. But would it, on a musical level, make lightning strike again?

Penderecki has moved on, writing numerous religious works in a more traditionally rooted language. There was a suspicion that the spectacular contemporary elements of his early pieces had been a sensationalist overlay. Put to the test, however, the Passion didn't come up that way. Its unsettling mix of slow, sustained blocks of sound and rapid dramatic pace, executed in strident colours at extremes of loudness and softness and a continuous high level of intensity, came up fresh as a risky but successful bundle of paradoxes that the composer simply never tried to repeat.

Even in the booming cathedral acoustic, which turned dense clusters of organ pedals, heavy brass and choral basses into pitchless rumbles, the impact was consistently thrilling and the narrative gripping – this despite the use of Latin in texts only partly familiar, adding psalms and other liturgical sources to the gospel crucifixion story. Boris Carmeli's resplendent and floridly Italianate projection of the reciter's role helped. So did a musical delivery more polished than of old, with three confident choirs raked up steeply, the National Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra largely invisible below them but playing with bite and passion, and bold vocal solos from Adam Kruszewski, Piotr Nowacki and Iwona Hossa.

Like Berlioz's big choral works or Verdi's Requiem, it has so much theatre that it could almost be opera, except that it awakens your imagination so fully that it is already complete in itself. It really should do the rounds again, if there's anyone else who could learn it to the exceptional standard that Canterbury experienced.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments