IoS classical review: Robert le diable, Royal Opera House, London H7STERIA, Queen Elizabeth Hall, London

Last-minute cast changes couldn't fix the problem at the heart of this production, that medievalism and irony don't mix

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.An overnight sensation in 1831, Robert le diable has long been a curiosity piece. Grandiose in its span, four-square in its orchestration, it's a doomy, boomy drama of inherited malice and redemptive love, all shuddering timpani, shivering flutes, anguished declamations and delicate coloratura. Difficult to sing, it is easy to mock. In 1868, W S Gilbert's parody, The Nun, The Dun and The Son of a Gun, ran for 120 performances, outstripping the original opera's run in Paris and setting the tone for Laurent Pelly's arch Royal Opera House production, the first since 1890.

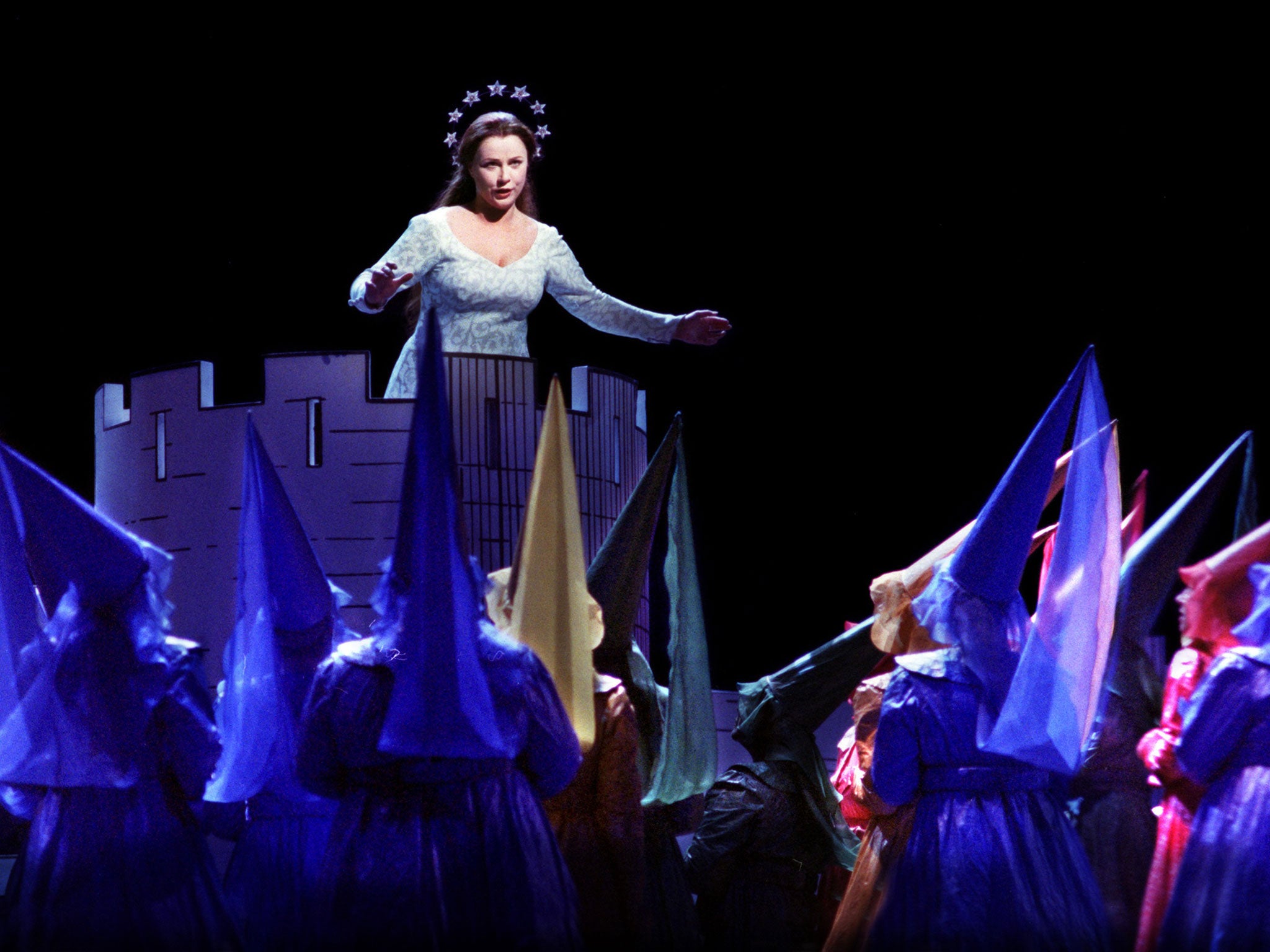

While all eyes have been on the last-minute cast changes, something far more deleterious has happened to Giacomo Meyerbeer's gothic fantasy. Tongue in cheek, little fingers raised, Pelly has placed a set of inverted commas around Robert le diable. Robert (Bryan Hymel) and Bertram (John Relyea) are 19th-century rakes, while the knights and ladies of medieval Palermo, their red, blue, green and yellow horses, their jousting court and their castellated paper palace, are straight out of a toybox (designs by Chantal Thomas).

If there is a concept at play, that concept is more concerned with 19th-century susceptibility to the supernatural than it is with the supernatural itself or with the demons we all have. While the singers sing it straight, Pelly assumes a pose of ironic amusement. The mountainside where Bertram reveals his true identity glows with Judgement Day animations of falling souls and demons with pitchforks. The bacchanalia of spectral nuns, as painted by Degas, plays out like a scene from Buffy the Vampire Slayer, all hissing, writhing and heavy breathing, as though the nuns were suffering chronic yeast infections. Only when the chorus rushes in for the last two minutes of that scene do you sense the opulent horror Meyerbeer intended.

Musically, there are grave problems, only some of them emanating from Meyerbeer, who set a French text to largely Italianate forms and orchestrated them in a German style. Moments that catch the ear are often borrowed from earlier composers (Mozartian cadences abound) or are familiar from later and better reworkings of similar material (Gounod's development of the seducer/seductee relationship in Faust). Conductor Daniel Oren needs more pep, verve and wit, more specificity in his sonorities, more zest. Ironically, the most idiomatic musical performance comes from Patrizia Ciofi, who stepped in as Isabelle only three days before the opening night, a small, agile soprano, fragile and saucer-eyed, exquisite in the cavatina "Robert, toi que j'aime". Hymel's gleaming voice is a couple of sizes too heroic for this quicksilver role but he handles the demands intelligently, his sound ideally placed for the nasalised vowels. Relyea has the low notes and the tone but lacks menace, a suburban Mephistopheles. Marina Poplavskaya's chilly, covered sound is a poor fit for the role of simple-hearted Alice, and her French is approximate. The a capella trio curdles violently but Jean-François Borras nails the style in Raimbaut's guileless aria, fresh and bright.

Only one of the voices in Charles Hazlewood and the BBC Concert Orchestra's H7STERIA event could properly be called hysterical, and it was more than 200 years after her death before she was diagnosed as such, by the pioneering neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot. Soeur Jeanne des Anges of the Ursuline Convent of Loudun was the first in her order to be possessed by the devil in one of the most violent episodes of mass hysteria in French history.

Written two years after Penderecki's opera on the incident, The Devils of Loudun, Peter Maxwell Davies's score for Ken Russell's film, The Devils, sets chaste plainchant over a tense soundscape of brushed cymbals and hushed alto flute, opening out into a squall of brass and a blowsy foxtrot. Ruby Hughes was the soloist, the madness and fury of Soeur Jeanne knotted into her jaw and throat.

The distraction in Schoenberg's Pierrot lunaire is of a different sort, capricious, fantastic. Allison Bell's interpretation was more sensual and playful than others I have heard, less intellectualised. The interaction with violinist Charles Mutter, viola player Timothy Welch, cellist Benjamin Hughes, flautist Ileana Ruhemann, clarinettist Derek Hannigan and pianist Danny Driver seemed easy, almost off-the-cuff, the text witty and sharp.

In the week that she won a British Composer Award for dance work DESH, Jocelyn Pook's Hearing Voices wove together fragments of recorded interviews with women who had experienced mental-health issues with spoken and sung texts from mezzo-soprano Melanie Pappenheim. Only rarely did Pook's glossy orchestral uplift directly reflect what was being said. When it did – when the violins or cellos imitated a particular tic or pattern of speech – the effect was striking. From the dementia patient Agnes Richter, whose densely embroidered asylum jacket was preserved after the First World War, to Aunt Phyllis, who kept detailed notes on her fraying sanity in the 1930s, and Bobby, Julie and Mary, the individual personalities were carefully and lovingly realised.

'Robert le diable' (020-7304 4000), to 21 Dec

Critic's Choice

It's a festive week with Opera Erratica, bringing holographs and Renaissance madrigals to Spitalfields Winter Festival at London's Hoxton Hall (Mon & Tue). Richard Neville-Towle and Ludus Baroque perform Bach's Christmas Oratorio with soloists Mary Bevan, Tim Mead, Ed Lyon and William Berger at Edinburgh's Queen's Hall (Fri). Marc Minkowski conducts the BBC Symphony Orchestra in Grieg's Peer Gynt, at London's Barbican Hall (Sat).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments