Dead Man Walking, Barbican, London, review: Grabbed us by the throat and never let go

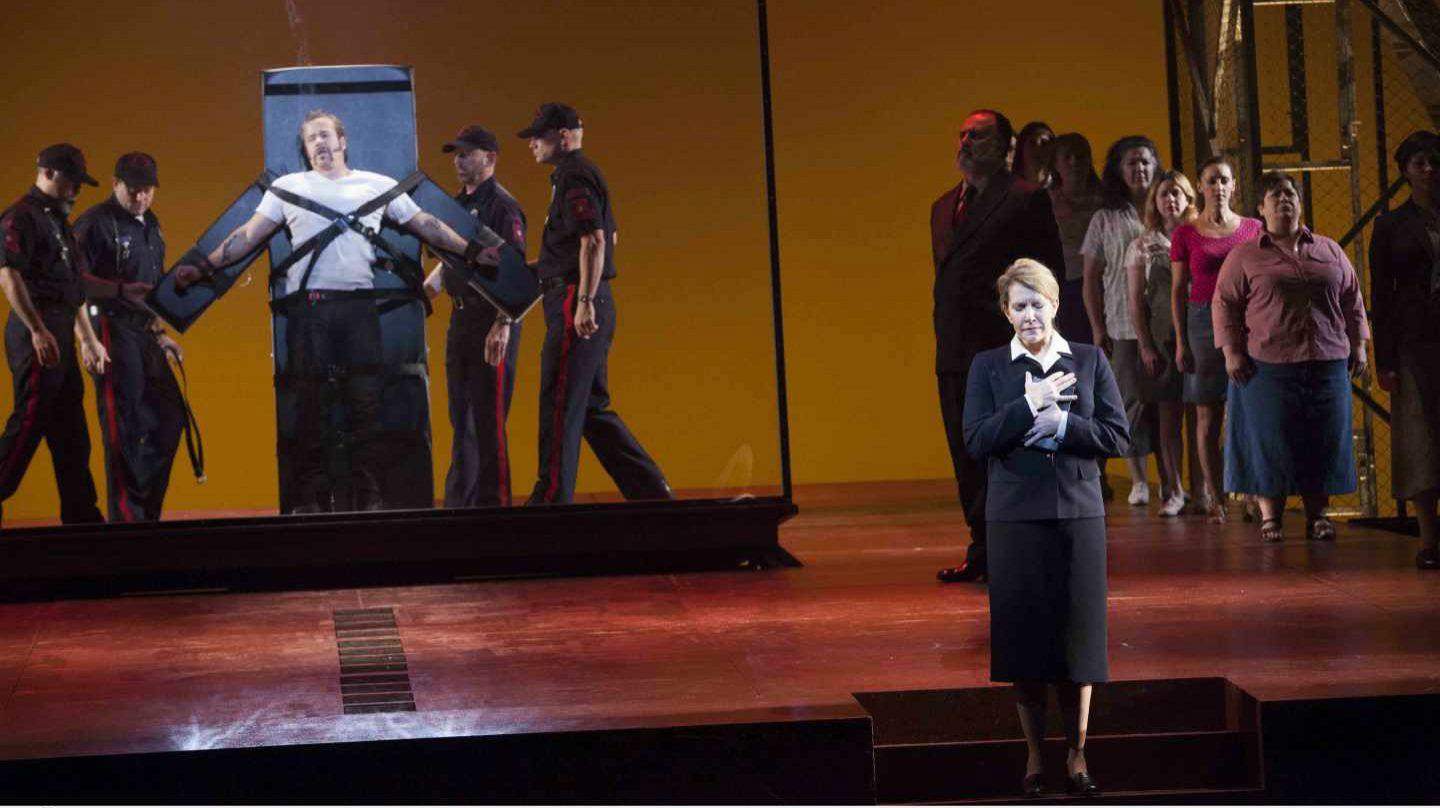

Joyce DiDonato stars as Sister Helen Prejean in the UK premiere of Jake Heggie’s opera, based on the nun's memoir, 'Dead Man Walking', which was also made into a 1995 film starring Susan Sarandon and Sean Penn

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.First the back story. A nun named Sister Helen Prejean was asked to write to a convict on death row in Louisiana who was due to die for a double murder; she accompanied him to the end, and in 1984 watched him die; since then she has been a tireless campaigner against the death penalty. She wrote a memoir, Dead Man Walking, which Susan Sarandon persuaded her husband Tim Robbins to make into a film in which she would play Sister Helen; San Francisco Opera boss Lotfi Mansouri then persuaded composer Jake Heggie to make an opera out of it, which premiered in 2000 with Joyce DiDonato as Sister Helen. During the intervening 18 years it has been performed in many places, but it’s only getting its London premiere now.

Terrence McNally’s libretto sticks closely to the original book, making it a story of redemption through love. Heggie’s lyrical, tonal, through-composed score comes out of the New York musical tradition, trailing strands of Sondheim, Bernstein, and John Adams, as well as hints of the blues and Southern spirituals. The resulting tapestry is bright and engaging, if lacking the imprint of a personal musical voice.

The Barbican stage was crammed, with the BBC Symphony Orchestra in full occupation while their male-voice chorus (incarnating the death-row cons) periodically burst into vengeful life from the rear, and a children’s choir – Finchley Children’s Music Group – marching out in front; a narrow strip of the forestage offered a suitably claustrophobic space on which the action – from prison cell, to visitors’ room, to death chamber – could unfold.

The film had an icy intensity, but the opera goes at white heat, and this performance, under the stage direction of Leonard Foglia and the music direction of Mark Wigglesworth, grabbed us by the throat and never let go, from the cinematically lit murder at the start to the crucifixion-like death on the gurney. DiDonato’s Sister Helen compelled total belief, the beauty of her singing flowed with the naturalness of ordinary speech; baritone Michael Mayes, as the condemned man, gave a searing performance as he was persuaded by his new spiritual adviser to shed thick layers of defiance and denial; Maria Zifchak, playing his mother with prosaically disbelieving bewilderment, tore the heart. One was aware at every moment that this drama was played out for real in 1984, and that it’s due to be played out again for real in America this coming Saturday, and doubtless will be again next month, with a different reluctant star, in some other Southern state.

No wonder this opera has had sixty international productions in its eighteen-year life. Musically and dramatically it still needs tightening, but the arias burn with passion and the choruses have elemental force. This performance was a one-off: the English National Opera would be the natural home for a proper run. What are they waiting for?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments