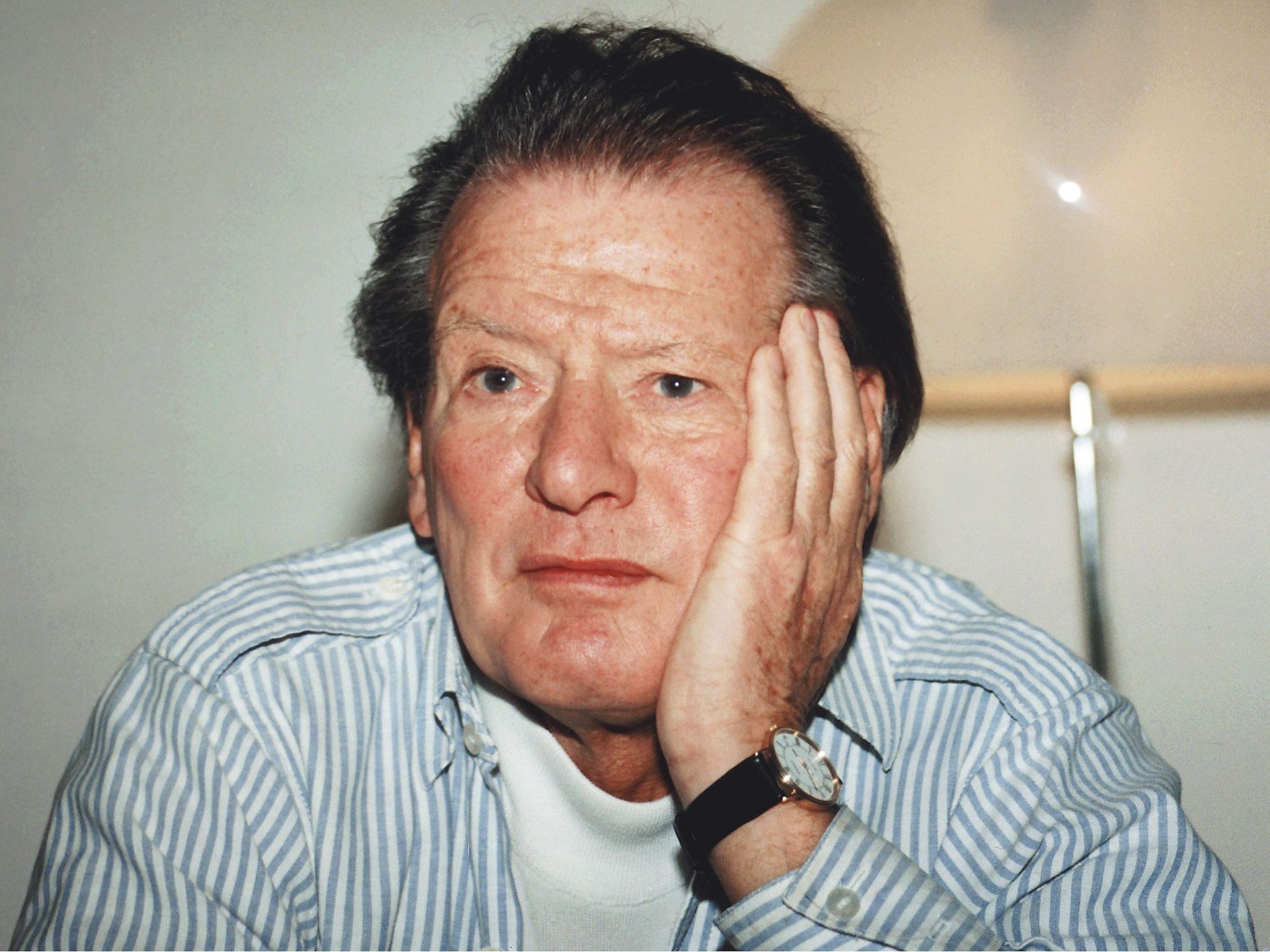

Obituary: conductor Sir Neville Marriner extended the horizons of the orchestra

Sir Neville Marriner was regarded as the one of the world’s greatest conductors, with an unrivalled range that covered the baroque era and the modern era, concert works and opera

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Sir Neville Marriner, who has died aged 92, was the most-recorded of any British conductor, and in the world second only to Herbert von Karajan. His repertoire was catholic and, having been a violinist and orchestral player, he understood the orchestra, and its members, and so gained their respect and cooperation.

He was born in Lincoln and, after lessons with his father and with the Nottingham-based violinist Frederick Mountney, he studied at the Royal College of Music and the Paris Conservatoire and at 24 was teaching music at Eton College. In 1950 he joined the staff of the Royal College of Music, but was already launched on a performing career as a member of the Martin String Quartet (from 1949), with David Martin, Eileen Grainger and Bernard Richards, and the Jacobean Ensemble (from 1951), with fellow violinist Peter Gibbs and the harpsichordist and scholar Thurston Dart. “Felicitous phrasing” and “miracles of grace and delicacy” were comments applied to some of the works in which he played at this time.

Marriner had met Bob Dart (survivor of an aircraft crash-landing) convalescing in 1944, after which began what Gramophone magazine has called “one of the key musical partnerships of the early music revival”. In 1952 Marriner was enlisted by Walter Legge to deputise in the Philharmonia Orchestra for concerts of music by Brahms conducted in London by Arturo Toscanini; he also played in recording sessions for Wilhelm Furtwängler.

In 1954 he joined the London Symphony Orchestra, becoming principal second violin two years later – a post he held until 1968. During this period, rather frustrated by the daily routine and variable standards, he and several colleagues, “refugees from conductors”, formed a chamber ensemble: “Entirely for our own pleasure”, said Marriner. “I don’t think we ever intended to give concerts.” But the group was soon invited to perform a series of concerts at the London church of St Martin in the Fields, whose name they adopted.

The first concert of the Academy of St Martin in the Fields, in November 1959, was attended by Jeff Hanson, husband of Louise Hanson Dyer, founder of the record company L’Oiseau-Lyre; he signed up the ensemble on the spot and launched them on a career in the recording studio.

Despite all the recordings, public appearances by the Academy were comparatively rare, but when they played a series of three concerts in the Queen Elizabeth Hall in early 1969, the critic Stanley Sadie remarked that “they showed themselves one of the most accomplished and quietly musicianly of chamber orchestras”. This series was a microcosm of the ensemble’s repertoire, encompassing Bach, Handel, Haydn, Mendelssohn, Stravinsky and Britten, among others.

When in 1984 Milos Forman came to make his film of Peter Shaffer’s play Amadeus, it was Marriner to whom he turned to look after the music. As the conductor later recalled, in the play there are six minutes of music; in the film, there is about an hour and a half.

Marriner was always disarmingly modest about his own abilities as a violinist – as if leader of the second violins in the London Symphony Orchestra was in some way not quite what one might have hoped for – but he often appeared as a soloist with the orchestra, for example in 1959 in Bach’s Concerto for Two Violins in D minor at the Royal Festival Hall with the orchestra’s then-leader, Hugh Maguire, and Walter Goehr conducting. The two soloists “were ideally matched and at the same time sufficiently contrasted so as to give the proper effect of antiphonal communion in music which must be as wonderful to play as it is to hear”. Maguire and Marriner played this piece together several times.

In 1958 the LSO was conducted in three concerts by Pierre Monteux, the great French conductor who in 1913 had given the first performance of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. In 1961 the LSO offered Monteux the principal conductorship, which was brief, because he died in 1964. But of these years Marriner said that Monteux “made [the orchestra] feel like an international orchestra … He gave them extended horizons and some of his achievements with the orchestra, both at home and abroad, gave them quite a different constitution”.

It was Monteux to whom Marriner went for advice on becoming a conductor, attending the maestro’s conducting classes in the USA. To begin with Marriner had led the ASMF from the first violin desk, but as the repertoire extended he began to conduct, and in 1968, while continuing to appear as a freelance instrumentalist, he left the LSO. In 1969, the newly formed Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra invited him to take charge: he accepted, leaving his violin at home. But he still saw his role in relatively modest terms (for a conductor) as “providing the musical skeleton. The flesh and character must come from the musicians themselves”.

In addition to guest conducting in the US and throughout the world, he was also music director of the Minnesota (formerly Minneapolis Symphony) Orchestra from 1979 to 1986 and principal conductor of the Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra from 1986 to 1989, while continuing to be associated with the ASMF in London.

The range of Marriner’s repertoire was enormous, from the baroque era to the 20th century, including Britten, Tippett and Nicholas Maw; not just concert works but opera too. He enjoyed the intensive rehearsing of opera, but the gaps between performances made him restless. “It’s never really caught my imagination”, he said. “I think I missed a great deal.”

In addition to a CBE in 1979, a knighthood in 1985 and being appointed CH in 2015, there were many other honours, including in 2014 a special Outstanding Achievement award from Gramophone magazine, “in recognition of his prolific and long-standing career in front of the microphone”. In 2015 he joined the Gramophone Hall of Fame, reserved for those “who have shaped the classical music recording industry”.

He had a puckish sense of humour, once remarking that “the awful thing about a conductor becoming geriatric is that you seem to become more desirable, not less. I just wish all these offers had come in when I was 30!”

As his colleague, the cellist Alexander Kok, has said in his own memoirs: “One of Neville’s many talents is an admirable gift for creating an atmosphere in which music can be enjoyed”, along with “his tongue-in-cheek attitude to both work and play”. Kok recalled that he “was given an insight into the lifestyle of bons viveurs” when Marriner and his first wife Diana were living in part of the Koks’ house in Bayswater.

Marriner’s manner on the podium was straightforward and business-like, with economical but elegant gestures that undoubtedly hark back to his time as a violinist.

The French classical pianist Lise de la Salle says that “Sir Neville is one of those rare conductors who convey – with both force and simplicity – all the grandeur of the music. He combines tradition, spontaneity, freedom and fidelity to the text in a unique way”.

Neville Marriner, conductor and violinist: born 15 April 1924; died 2 October 2016

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments