The Schubert Project: Classical music festival in Oxford to play all 600-plus songs by Austrian composer Franz Schubert

There is no doubt that this year’s all-Schubert Festival will be a potent affair

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Franz Schubert was the first middle-class composer.

Rather than relying on aristocratic patronage, he became financially self-sufficient by tapping a slowly emerging publishing industry to disseminate his music. Knowing his audience well, Schubert wrote hundreds of songs which could be performed by ordinary people in their homes. But he refused to pander or patronise; his songs are among the most emotionally and psychologically acute ever written. Next month, the Oxford Lieder Festival performs the complete set for the first time in Britain.

There are well over 600 Lieder in Schubert’s catalogue. Led by Festival artistic director Sholto Kynoch, some of the finest singers, pianists and musical experts will explore the composer’s legacy via a programme of concerts, lectures, films and plays. The aim? To bring Schubert’s Vienna to Oxford.

But what was his Vienna like? Thoughts of the Austrian capital immediately conjure images of cream cakes, whirling dances and lavish palaces, but life was far from easy for Schubert. Born in 1797 by the kitchen hearth – the only warm spot in his family’s home – he grew up during the tense Napoleonic era, when the powers-that-be had battle campaigns rather than evenings of song on their minds. But Schubert continued to fight for recognition until his early death in his brother’s damp apartment aged 31.

The support of friends and the emergence of a culturally voracious middle class, as well as innovations in music publishing and piano manufacture, all helped him earn his crust. But he also had to contend with political repression. Following the defeat of Napoleon by Austria and its allies, State Chancellor Klemens von Metternich tried to crack down on revolutionary sentiment at home. All publications, songs, poems and posters were subject to censorship laws, maintained by a vicious secret police. Schubert’s own clique of writers, painters and musicians faced raids and arrests, with his friend, the poet Johann Senn, detained for championing anti-establishment ideas and deported to the Tyrol.

However, such constraints couldn’t prevent public music making entirely, and although Schubert penned a series of symphonies and operas, the city’s musical culture largely survived within a domestic setting; luckily, Lieder thrives on intimacy.

Schubert’s first song appeared in print when he was 21 and although publishers repeatedly turned down his orchestral, piano and chamber works, Schubert’s Lieder always grabbed the attention. Many of these songs were first heard at the social gatherings that formed part of the new ‘bourgeois public sphere’, to use a term coined by sociologist Jürgen Habermas. Out of the state’s reach, this domain of debate and conversation thrived within the coffee houses and public squares of Europe’s great cities. But in the suspicious Metternich’s Vienna, it was forced indoors. Schubert provided its soundtrack, small in scale but with big enough ideas to enhance and radicalise the domestic sphere.

Pushing the bounds of what could be tolerated in such a setting, Schubert significantly upped the emotional ante. When his friends heard his song cycle Winterreise (“Winter Journey”) at a private performance in 1827, they were “dumbfounded by the gloomy mood”. Based on a series of poems by Wilhelm Müller, the cycle depicts the progress of a world-weary existential traveller – a type that Schubert, who suffered from syphilis for the last six years of his life, knew all too well.

Schubert’s self-identification with the characters and quandaries depicted in his songs became an increasingly prevalent trait as he neared the end. “An extraordinary number of his songs deal with death,” Richard Stokes, Professor of Lieder at the Royal Academy of Music, writes in a new collection of essays to accompany the 2014 Oxford Lieder Festival, “not because it was a fashionable Romantic trope, but because much of his life was lived in its shadow.”

Like those friends who heard Winterreise for the first time in 1827, audiences today are often shaken by the sincerity, subjectivity and self-analysis of Schubert’s music. Even an early song such as “Erlkönig”, composed when Schubert was just 18 and setting a text by Goethe, is a gut-wrenching experience, deftly aligning our emotions with those of the poem’s grief-stricken father-narrator. Realising that an invisible spirit has killed his child, the father’s voice fails, the driving piano accompaniment relents and we too are left tormented by his loss.

The true strength and beauty of Schubert’s Lieder, however, is that they are as cerebral as they are sensitive. And what makes a complete survey of his songs “a major undertaking in anyone’s book”, according to tenor John Mark Ainsley, who sings in the opening concert of the Festival, is the broad range of their literary and philosophical sources.

Schubert didn’t remotely blanch at setting figures like Goethe, Heine, Schiller and Shakespeare. He had a firm grasp of the tenets of Romanticism and perfected a new genre, the song cycle, brimming with dramatic and psychological possibilities. Schubert’s formal ideas and harmonic choices were also consistently bold, revealing layer upon layer of significance within the poems he chose to set. As pianist Roger Vignoles says, Schubert “invented the art form and he got it right from the beginning”.

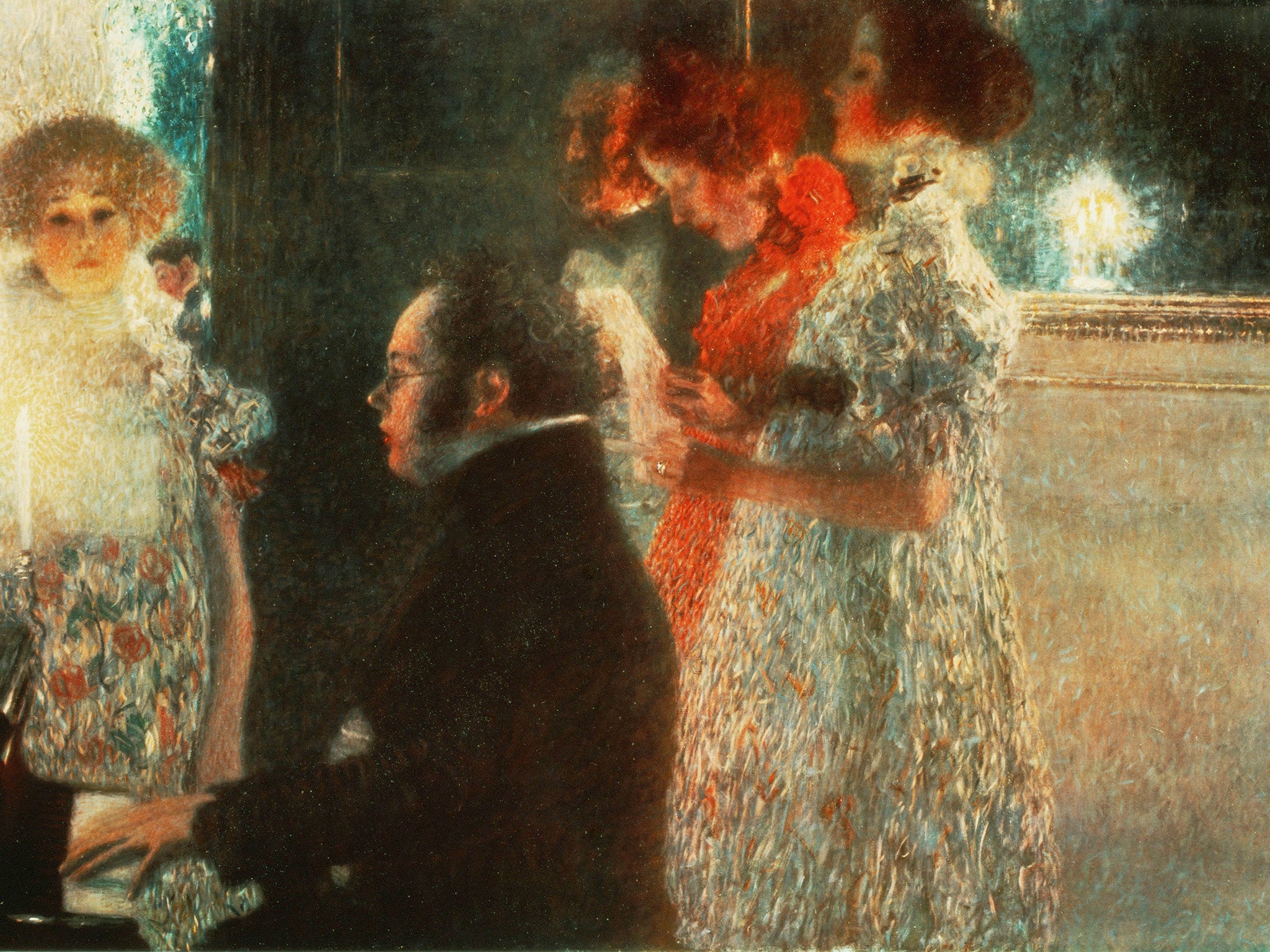

There is no doubt that this year’s all-Schubert Festival will be a potent affair. “There is something uniquely personal about singers and their involvement in this work ... you can’t help but be pulled in and share it with them”, says Kynoch. By moving away from powdered wigs and courtly patronage to the candlelit confines of the private home, Schubert was able to unleash greater emotional and musical freedoms than had previously been imagined. You just have to be brave enough to face his radical and passionate music 200 years on.

‘The Schubert Project’ runs from 10 Oct to 1 Nov. Gavin Plumley will give the opening lecture of the Festival at the Holywell Music Room, Oxford, on 10 Oct at 5pm (oxfordlieder.co.uk)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments