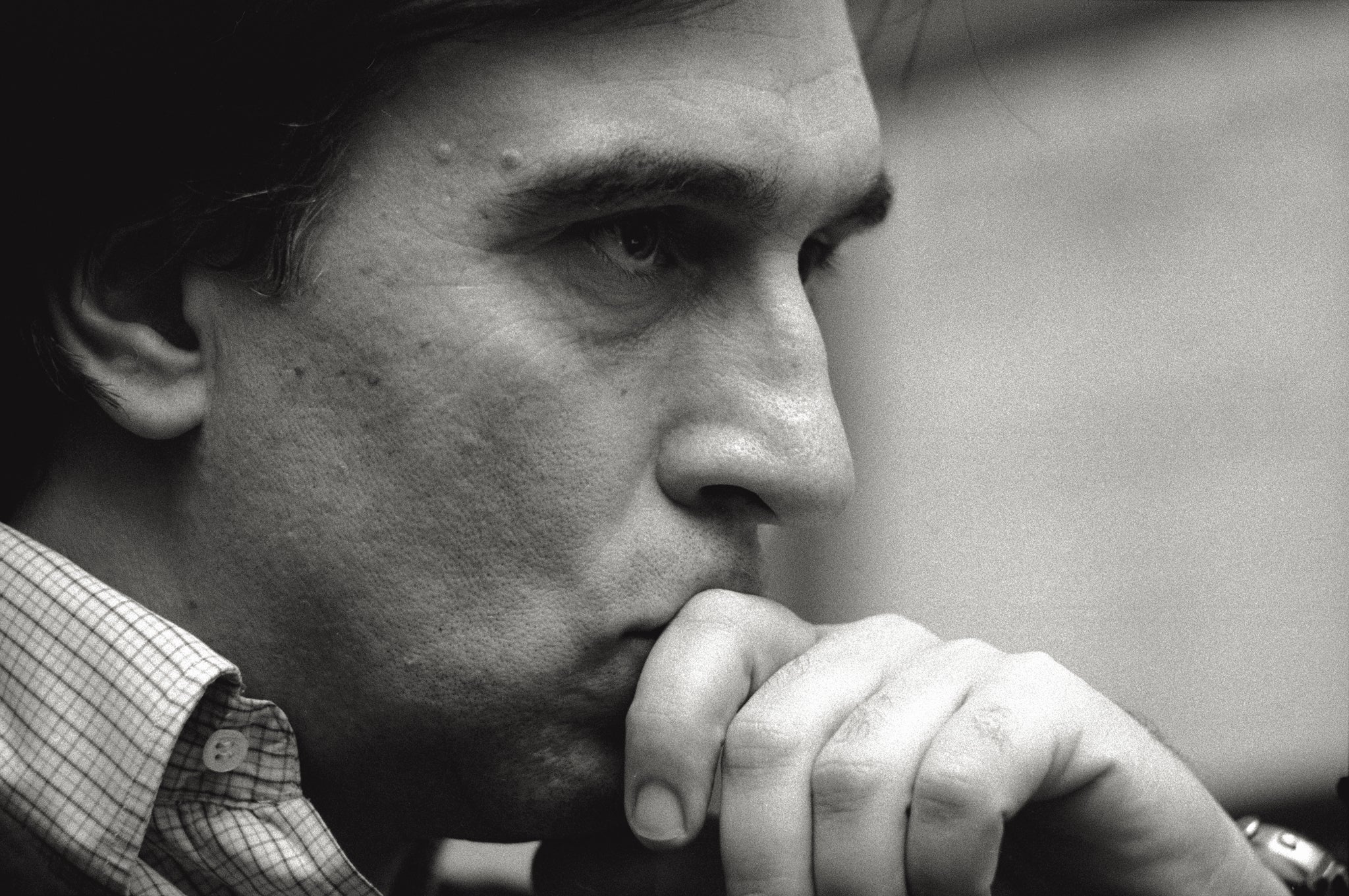

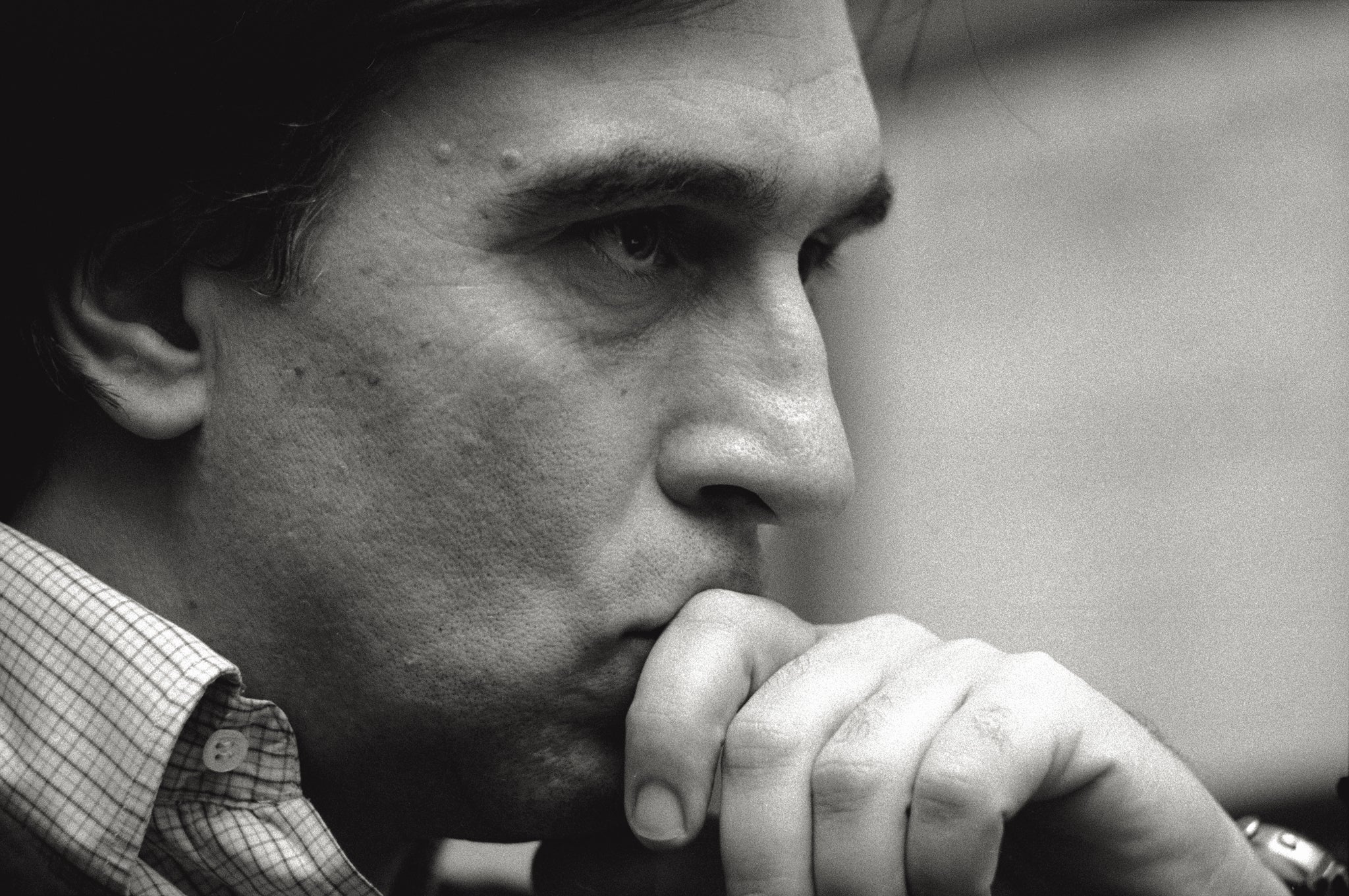

Claudio Abbado dies aged 80: An appreciation of the late conductor

No wonder he was widely considered the finest conductor of his day, he was certainly the best-loved of them all, writes Jessica Duchen

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Claudio Abbado’s Mahler Symphony No.9 with the Lucerne Festival Orchestra is among those rare concert experiences that will stay with me forever.

At the end the strings faded into the ether as if merging with an ineffable, eternal life force; you could scarcely tell where sound stopped and silence began. The level of intensity that this extraordinary conductor summoned from his players could lift a musical masterpiece from the great to the utterly transcendent – a quality audible not primarily at the moments of greatest volume, but rather at the quietest.

No wonder he was widely considered the finest conductor of his day; he was certainly the best-loved of them all.

It was not the monumental in music that set him apart, but his humanising of it. He approached orchestral works as chamber music, giving his players space to contribute their own artistry, drawing them out with his ability to listen – and often with his sense of humour – rather than imposing a will of iron.

The results were supple textures, clear, warm and beautifully balanced, with an exceptional capacity for intimacy: Bruckner, Verdi and Brahms are just a few of the composers whose creations in his hands could flower into unsuspected territories. Mark Wilkinson, president of Deutsche Grammophon for which Abbado recorded over 46 years, describes him as “a man who put himself entirely at the service of the music he conducted and, in doing so, made listeners feel that they were hearing it properly for the very first time.”

Abbado first began to draw public attention when he won the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s Koussevitzky Prize at Tanglewood in 1958; he made his debut at La Scala, Milan, two years later.

He went on to hold a succession of the world’s most prestigious posts, including music director of La Scala (1968 -86), the London Symphony Orchestra (1979-1987) and the Vienna State Opera (1986-91), as well as general music director of the city of Vienna from 1987.

The Berlin Philharmonic’s members elected him to succeed Herbert von Karajan as its artistic director in 1979, yet he stunned his fans by leaving after13 years. He never took a directorship in the US, though, saying in interviews that he did not wish to battle union regulations on rehearsal time. His musical standards were exacting; he was willing to give everything to achieve them and expected nothing less from his players.

As champion of youth orchestras, new music and the widening of audiences, Abbado’s impact on concert life was simply immeasurable. In Milan he presented concerts for students and workers; in Vienna, he established the Wien Modern Festival, now a crucial event in the contemporary music calendar; and he founded the European Union Youth Orchestra, which later became the Chamber Orchestra of Europe, plus the Gustav Mahler Youth Orchestra and the Orchestra Mozart (though the latter closed down last week, apparently unable to continue without him). In 2003 he spurred into existence the Lucerne Festival Orchestra, its players hand-picked and as dedicated to him as he was to them.

His last appearance was a performance with the LFO of Bruckner’s Symphony No.9 at the Lucerne Festival in August 2013. The festival’s chief executive, Michael Haefliger, recalls: “There was a sense in the hall that it might possibly be his final concert, so far removed and deeply transfigured did Claudio Abbado seem to all of us on this unforgettable evening, in this moment of unfathomable silence.”

Claudio Abbado died in the early hours of Monday morning in Bologna, with his family at his bedside. In 2000 he had been diagnosed with stomach cancer and underwent drastic surgery that left him thereafter extremely slender and apparently physically frail; sadly the disease caught up with him in the end. Those close to him report that in his last months, talking about music would always lift his spirits. His musical legacy will continue to raise ours, even though he is no longer with us.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments