When Scott Walker met Francis Poulenc

The Royal Opera is pushing boundaries in a new show which mixes music, dance and two very different composers. By Jessica Duchen

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A woman, a telephone and one side of a conversation – it sounds like the train journey to work? Not quite. Instead, it was a situation of measureless dramatic potential for the great French author and artist Jean Cocteau, and the composer Francis Poulenc. The latter's one-act opera for one singer, La Voix Humaine, setting a monologue by Cocteau, is the proof.

This short, searing work forms half of an exceptional cross-genre evening, Cocteau Voices, which takes to the stage this month in the Linbury Studio of the Royal Opera House. The Poulenc opera is the second part of the performance; before the interval there's a new ROH2 commission, a dance work by Aletta Collins, also inspired by a Cocteau monologue, and set to music specially composed by Scott Walker.

Striking a balance between art forms, between intense emotion and a light Gallic touch and between four potentially very different audiences – for dance, opera, literature and Scott Walker – Collins and the director Tom Cairns, who tackles the Poulenc, have set out to share the challenge.

They first worked together on Cocteau's themes of abandonment and possession in a film for Channel 4, The Human Voice; now they are deepening the connection and moving it on to the stage. Although the two halves of the evening are separate works, there's a unity at what Collins terms "bedrock level", evolved through long familiarity with one another's work; they have also laid the foundations by jointly planning the overall look and feel of the evening.

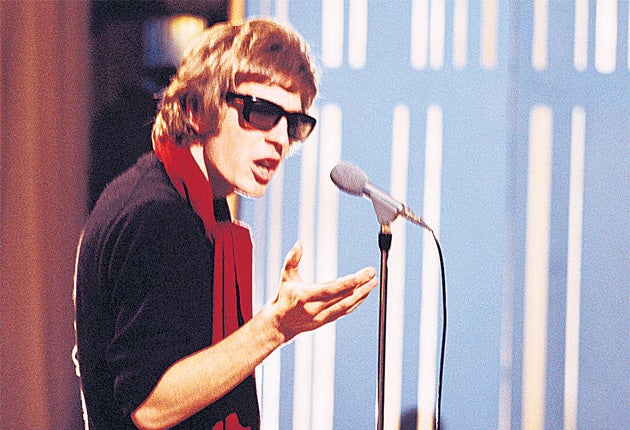

Nevertheless, as Tom Cairns says: "There couldn't be a bigger contrast between Scott Walker and Poulenc." In the 1920s, Cocteau was mentor to the group of composers known as Les Six, which included Poulenc, helping to inspire groundbreaking ideas on the nature of French art. But now his influence has virtually time-travelled. Walker, the legendary singer-songwriter whose recordings with The Walker Brothers first hit British pop charts back in the 1960s, is one of those maverick musicians who are constantly reinventing themselves. In the late 1960s he immersed himself in studying classical music, including Gregorian chant, which substantially affected his compositions afterwards; his kaleidoscopic musical imagination has continued to astonish, and in 2006 he was immortalised in film as 30th Century Man, a documentary by Stephen Kijak for which David Bowie was executive producer.

Collins first worked with Walker in 2008, when songs from his albums Drift and Tilt were presented at the Barbican as Drifting and Tilting: The Songs of Scott Walker. "A great range of performers were involved, from Jarvis Cocker to Damon Albarn," Collins says. "I was asked to choreograph two songs – one was a solo dance and the other was part of a larger piece, Clara (Benito's Dream), about Clara Mussolini. That was the famous piece with pig-punching: the carcass of a pig is punched and the noise of that becomes the percussion sounds. It was just fantastic to get to know Scott through working on that project.

"Then, when Cocteau Voices came up 18 months later, Scott was the most exciting choice. It was a collaboration from the word go. The score he's written is absolutely amazing; though it's in no way related to the Poulenc piece, I think the scale, weight and emotional intensity balances it very strongly."

Duet for One Voice was inspired, says Collins, by an early draft of the 1932 monologue that eventually evolved into Le Bel Indifférent. Cocteau created the latter for Edith Piaf and worked into it many of her own experiences. The earlier version, though, was a radio play, Lis Ton Journal ("Read Your Newspaper") written for Cocteau's male lover, Jean Marais. "That ambiguity, the fact that it can be performed by a man or a woman, was exactly what attracted me to it," says Collins, whose ballet features six dancers – three men and three women.

Both the Cocteau monologues behind this project deal with people desperately trying to get their partners' attention – and the issues are painful and perennial: "We read in magazines every day about the same kind of relationship problems and break-ups," Cairns says.

In La Voix Humaine, the heroine has been dumped by her implicitly younger lover and speaks to him by telephone; we hear only her side as the opera traces her mental breakdown, the question remaining as to whether she ultimately takes her own life. "You really have to write the invisible ex-lover's side of the conversation," Cairns says. "The text is very specific and the drama keeps revolving on virtually 180-degree turns, so it's something that the director and the performer have to figure out – the soprano, in this case the wonderful Nuccia Focile, carries the whole show alone and it's essential that the character evolves from her viewpoint."

Poulenc took Cocteau's monologue exactly as he found it: "I think he set every word, without missing a beat," says Cairns. And the intimate Linbury Studio should enhance its power: "We're putting the set in front of the orchestra, so Nuccia will be only a few feet from the audience."

Could there be a greater future for this type of mixed-genre performance in general? It's an endeavour "fraught with danger," Cairns and Collins admit. "There's always the risk that people will come along for one part and not respond to the other," says Cairns.

Such presentations have become increasingly featured in arts festivals both in Britain and overseas; what's newer is the advantage of the Linbury Studio as a venue that can commission and handle creative experiments year-round. In straitened economic times, though, the chances are that risk-taking will become ever more a luxury for creative artists – and for their audiences. Still, Cairns adds: "You often bump into people in the rehearsal room, but this time it's different: everyone's headed towards the same end-product. We can't wait to see each others' work at close quarters – and that sort of collaboration is rare."

'Cocteau Voices', Linbury Studio, Royal Opera House, London, 17-25 June (020 7304 4000)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments