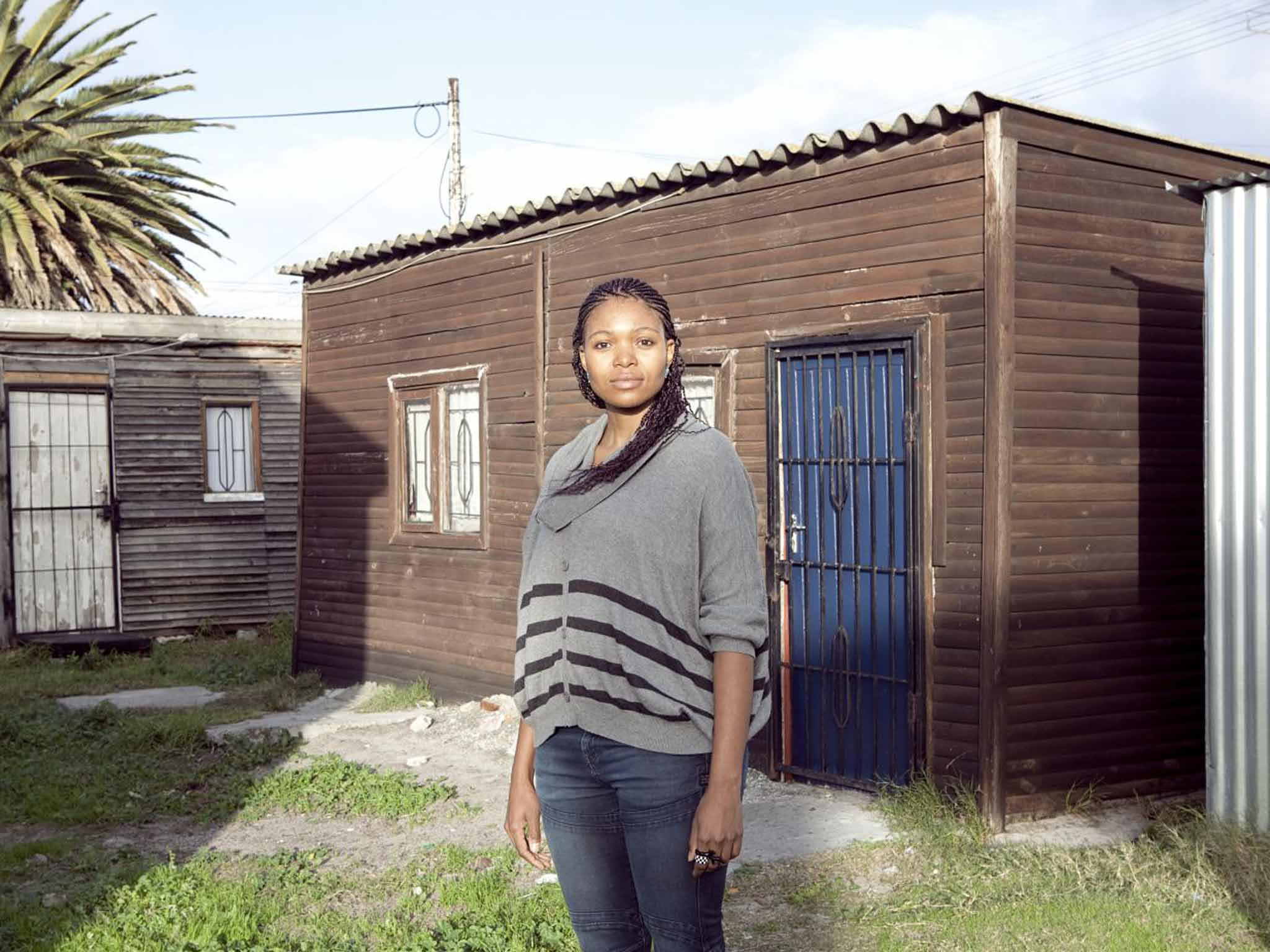

Pumeza Matshikiza on soprano megastardom, her township education and why the ANC is a stuck record

She is the leading light of a generation of opera stars to have burst out of the townships post-Apartheid. But the superstar soprano Pumeza Matshikiza has little faith that the ANC is making it any easier for ambitious young South Africans to call their own tune

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the world of opera, a young star's path to fame usually moves through incremental steps: well-received recordings, high-profile recitals, new stage roles at some prestigious house. The soprano Pumeza Matshikiza – one of an outstanding generation of young South African singers who have made a global impact since the end of Apartheid – has done all that.

In July, however, the 35-year-old broke through another sort of barrier when she sang Hamish Henderson's 1960 protest song "Freedom Come-All-Ye" at the opening ceremony of the Commonwealth Games in Glasgow. "They wanted something to bring people down and focus a bit," she recalls as we talk in an eerily empty boardroom at the Decca offices in London. "I think it worked well in the stadium.''

That's something of an understatement. Yet when a trained voice as rich, warm and expressive as hers reaches a huge "crossover" audience via such a gig, those new admirers don't always hear its authentic sound. "It was more like crooning," she says. "They wanted the song not in the full operatic way, but like a lullaby." Her foot still in plaster after a fall that failed to disrupt a packed autumn schedule, she sips her tea and talks in the measured, thoughtful and frank tones of someone whose self-directed progress from township to limelight has left little room for showbiz gush. Garlanded soprano she may be, but Matshikiza remains a clear-minded, highly focused artist, not a spangled luvvie.

Her debut CD, Pumeza: Voice of Hope, blends African songs in Xhosa, Zulu and Swahili with gloriously sung arias by Puccini and Mozart – two of her favourite composers. Listeners now expect Africa's best voices to straddle both kinds of repertoire, without thinking about the burdens that this cross-cultural eclecticism imposes on the voice. "It's a different kind of technique," Matshikiza explains. "With the operatic pieces, you use your full voice, your full body… with African music, it's something between the speaking voice and the crooning voice." When rehearsing for a concert that embraces the sounds of two continents, "I always have to start with opera and finish with the South African music. It's difficult to do it the other way."

Coincidentally, the anti-racist song she "crooned" so sweetly in Glasgow includes a reference to Nyanga: one of the poor Cape Town suburbs in which Matshikiza grew up, after an early childhood in the Eastern Cape: "That was a sweet surprise, in a way."

Over the past decade or so, the emergence of an ever-growing band of world-class singers who hail from places such as Nyanga has thrilled classical-music fans. Apart from Matshikiza, South Africans such as Pretty Yende, Njabulo Madlala, Tsakane Maswanganyi and Nkosazana Dimande have regularly won prizes, wowed audiences and pocketed recording and opera-house contracts across Europe and North America. In a ruthlessly competitive global business, black South Africans have triumphed. All just a few short years after the fall of a system that denied them even a rudimentary musical education. As Matshikiza points out, "The talent was always there, but it was just not used – there were no opportunities."

It has taken hard graft, burning dedication and even a few lucky breaks to convert those home-grown gifts into worldwide opportunities. Like many of her peers, Matshikiza sang in school choirs, and absorbed the rich a cappella traditions of Xhosa music-making. Around her, the townships seethed and burned as the uprisings of the late 1980s heralded the downfall of Apartheid. She remembers that, "I heard opera on the radio when I was about 14 or 15, and that was just another dimension." Via recordings of singers such as the Swiss soprano Edith Mathis, "I heard people singing in such a smooth, detailed and very polished way." She thought, "I would like to sing like that. That is just heavenly, out of this world. How can I do that?"

Apartheid ended, but life as a diva still felt inconceivably remote. "On the street where I lived, I was the only teenager interested in opera. To learn one aria, I remember, it took me ages." What's more, "You were always singing a capella and never had a piano or instrument accompanying you and keeping you in tune."

At the University of Cape Town, Matshikiza initially studied to be a surveyor. Yet the lure of the university's College of Music proved too strong, and she trained as a singer there. With musical theory, she had some catching up to do: "The things I was learning at 21 were things that someone should have learnt at five or six! I still feel a bit disabled because I cannot play the piano, for instance." Yet that lack of early hot-housing brought benefits as well: "You develop your hearing. Your ears are so open."

She first sang on stage in 2002, in a work written by composer Kevin Volans for the Handspring Puppet Theatre (later of War Horse fame). Volans heard her and, mightily impressed, offered to pay her airfare to London for an audition at the Royal College of Music (RCM). "I don't think he thought he was launching someone," she recalls. "He was just being himself: the kind person he is – one of the kindest men I've ever met. It's not just me that he's helped." Once at the RCM, "They gave me a full scholarship there and then." Next, she moved to the Royal Opera House, a beneficiary of the Jette Parker Young Artists programme, and on the Covent Garden stage sang a range of roles – from Mozart to Smetana and Strauss. At first, London was a shock: "You can imagine, I came in September and we were going towards winter. I had never seen anything like it before! By 3pm it was dark outside, day after day after day. And people are so busy… I never thought I would get used to it, but eventually I did."

Winner of the Veronica Dunne international singing competition in 2010, Matshikiza joined the Classical Opera Company, picked up another award for the title role in Mozart's Zaide, then moved to Stuttgart Opera in Germany on a three-year contract that she has just renewed. (She is currently based in the city).

After the Commonwealth Games came a starring role at Proms in the Park, followed by a European recital tour with the Mexican tenor Rolando Villazon. Voice of Hope has picked up rave notices from some notably hard-to-please critics, and next month, she will lead a week of Christmas concerts with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic. "I have been very fortunate and I am forever grateful for how things have opened in my way," she says. "It's as if there's an angel looking after me."

Nonetheless, she warns that, for others, the struggle continues. Hope remains in short supply, not only for aspiring opera singers in South Africa but for her nation. Will her successors still need to build their careers overseas? "I think it's going to be the case for a long time. We still have lots of problems, that's the thing. And, in a way, opera is still a luxury in a country where there are people who have no water, no sanitation, and unemployment." All the same, thanks to the work of companies such as Cape Town Opera, "Opera is not doing badly there. It's accessible for those who are interested."

Even two decades after Apartheid, argues Matshikiza, her country has a tendency to squander its indigenous talent. "What I find when I go to South Africa is that the level of education in general – not just music education – is still very low. When you think about it, the biggest problem during Apartheid was that the majority of African people were starved of education. And now you have an African government not realising that education is the way to go."

Are things easier now for the next generation of ambitious young South Africans than for her peers? "It seems to me that it's just the same [as at the time of transition to majority rule in the mid-1990s], because we still have a lot of informal [shanty] housing – people living without sanitation. And youth unemployment is too high."

Mincing few words, she adds: "We are struggling with corruption, with mismanagement by our government. It is sad, because people hoped that when the ANC got into power, things would be better for everyone… It's one thing to fight for freedom, but another to be responsible for the country." She insists that "I'm not talking against the ANC, I just think it is very important that we Africans be accountable and responsible. We cannot forever point the finger at colonialism, at Apartheid – these things at some point will be irrelevant. If we based life on revenge, there would not be a single person alive in the world."

So future Pumezas will still have to fight to make their voices – however beautiful – heard around the world. "Life promises you nothing," she says. "It's an open slate where you improvise." For any young talent, self-help must precede outside patronage. In her early days, whenever she wanted to know something, "I'd go and ask. I had no other option but to keep on moving, to keep on doing things, not to sit in one place and to think, 'Oh, this is my situation – life is so far from me.'" In music, but not only in music, she has some advice for every young hopeful: "Launch yourself into the deep end."

'Pumeza: Voice of Hope' is out now. Matshikiza will appear at Liverpool Philharmonic Hall (liverpoolphil.com) with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra from 18 to 23 December

The new voices of South Africa

Tsakane Valentine Maswanganyi The soprano, who grew up in Soweto, studied music at the University of Pretoria. She has worked with the opera band Amici Forever, sung for Nelson Mandela, taken the lead in Porgy and Bess, and had roles in Puccini, Verdi and Mozart operas.

Njabulo Madlala Raised in a Durban township, the baritone studied in London and Cardiff, and won the 2010 Kathleen Ferrier Prize. He has appeared in operas around Europe and is an acclaimed recitalist. His solo CD Songs of Home ranges from African folk songs to German lieder.

Pretty Yende Born in Piet Retief, the soprano studied in Cape Town and at La Scala in Milan. She was a victor at the 2011 Operalia awards, and premiered at La Scala as Mimi in La Bohème. In 2013, she made a sensational debut at the Met in New York in Rossini's Le Comte Ory.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments