Medea: How Goldfrapp scored the Greek tragedy

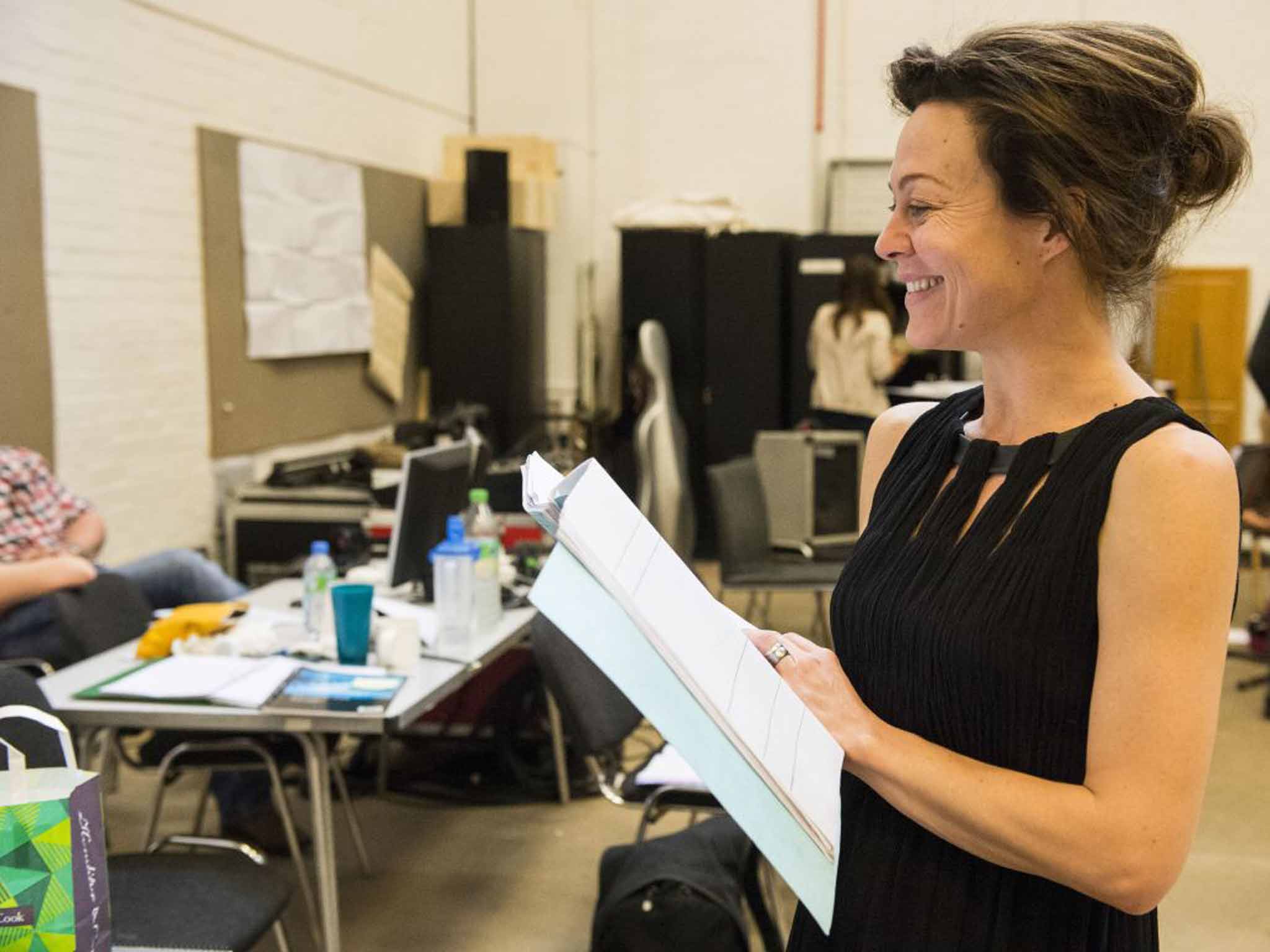

The National Theatre's production of the Greek tragedy 'Medea' addresses itself to the modern condition, helped by music from the art-pop duo. Holly Williams goes backstage

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.How do you solve a problem like Medea? Euripides's play, in which a mother murders her own children as revenge after her husband marries another woman, can be seen as a pinnacle of Greek tragedy: it doesn't get any more howlingly painful than maternal infanticide. And we are still drawn to the Greeks for this epic scale, the power of the poetry, that heightened sense of the mythic. And yet drama also needs to speak to our own times, our own condition.

Balancing these two elements isn't necessarily easy – but a new production at the National Theatre is throwing everything at it, creating a total-theatre vision that should soar to the necessary heights. Carrie Cracknell directs an all-new, trimmed and sculpted script by NT associate Ben Power. But the biggest coup, perhaps, is that Goldfrapp – the acclaimed music duo whose oeuvre slides between electro-pop and ethereal folk – are scoring the show, writing music for a live band and Chorus. The Chorus will also dance, with choreographer Lucy Guerin in charge of movement. This Medea will see the Olivier stage transformed into a simmering melting pot of poetry, song, movement and music.

"[The production] has a contemporary aesthetic; we wanted the characters to be as recognisable as possible," explains Cracknell. "But I felt it also needed to have a relationship to a world with gods and curses and magic and poisoned robes. If you rip it completely into a very non-spiritual modernity, you can break the idea structure of the play."

With NT regular Helen McCrory as Medea, they've got an actress who can blend those two elements – combining sarcastic modern speech in her direct address to the audience with a charismatic sense of some higher power. For Medea has supernatural skills, and in the original ultimately becomes a dragon-chariot-riding demigod: a climax which might not fly in a production that has at least one foot in 2014…

But Power and Cracknell were keen to not do away with that witch-y potency altogether. "There's a danger and mystery to her," says Power. "It's characterised by some in the play as 'magic', but what that means is up for grabs. What would be great is if the audience were allowed to watch this play, and it be perfectly conceivable that magic is real, or that magic is a metaphor for a certain kind of power, personality, difference."

Cracknell and the designer Tom Scutt took to watching horror movies for inspiration: "I think we're much more comfortable exploring magic and the supernatural in cinema," she observes. They were influenced by that cinematic confluence of the natural and supernatural: there'll even be a spooky forest onstage…

And it was when discussing how to create a world spiked with the supernatural that Cracknell and Power thought of enlisting Goldfrapp. It's a canny choice: on their albums, Will Gregory's music and Alison Goldfrapp's ethereal vocals create lush, dense atmospherics.

"It's about giving that heightened sense of the other – the celestial or the primal – and music can do that," says Power, adding with an enormous grin, "we're ridiculously fortunate to have Alison and Will." Their five musicians – three strings, an accordion and percussion – will be on stage, a part of the story. And while the Chorus of 13 women will have their usual role as the play's moral compass, leading an audience through sympathy to horror towards Medea, they're a carefully selected group of professional dancers and top-flight singers.

"The Chorus [has] this dual role of being the music and the text which is quite a... puzzle!" laughs Gregory. Scoring music for the theatre was a totally new experience for the pair; when we meet during rehearsals, they're still looking a little shell-shocked by the process. "Carrie is exploring things all the time which is wonderful, but it does mean you come in the next day and a whole idea has been changed."

Is that freeing or frustrating, I ask? There's a silence, a wriggle, a small laugh, before they conclude that ultimately: it's both. "It's like writing music for a film you haven't seen," says Goldfrapp. "It's quite a slow process, because you are spending a lot of time watching everything else... things are just ever evolving and changing. We don't know the lengths of [pieces of music], when they're starting, when they're ending" – she lets out a cackle of delight and fear – "it's quite bonkers."

They're both very clear they're just one part of the jigsaw of the show; anyone expecting "Medea: the Goldfrapp Opera" will be disappointed: "I don't know what the 'Goldfrapp sound' is. We're not thinking about that. You shouldn't be coming to hear Goldfrapp," she insists. "You should be coming to be amazed by the play!" adds Gregory.

As Goldfrapp's music keeps evolving, so too does Guerin's movement. She'd anticipated the Chorus would be a formal construct, speaking and moving in unison. "But we've found that actually that becomes quite stiff, too predictable, so a lot of it is more split up now. But it does build – in the final dance, this horror and energy really takes over the whole stage."

"The Chorus is the place where the ancient and the modern most bash up against each other," explains Power. He acknowledges long, lyrical sections of unison speaking can be jarring to the modern ear: what to do with the Chorus becomes a major artistic decision when staging any Greek tragedy. "There is a version of the Chorus where they are 13 totally individual people, separate lines; then there's the version – the version the National Theatre has done really successfully, Peter Hall with The Oresteia and many others – where it's something formal, structured, singing and speaking in unison."

Cunningly, their Chorus might do both: "It feels at the moment like there is a journey for the Chorus over the course of the evening from one thing to another, as the play ramps up, as the stakes get higher." So as they all move inevitably towards Medea's final, horrific, desperate act of unbelievable savagery, Guerin's choreography may become muscular, more unified, Goldfrapp's music ascend greater heights. Really, who needs a dragon-pulled chariot?

But for all the spectacle, Cracknell's take on the tragedy is also firmly rooted in human psychology. She wants it to be completely relatable for a modern audience. "What's extraordinary about the play, given how ancient it is, is that it does still feel very present, very contemporary. She is the archetypal vulnerable, abused single mother," says Cracknell, dubbing it the ultimate divorce drama, and suggesting that we've all seen (albeit to a less dramatic degree) children neglected in the aftermath of a ferocious break-up. She even got a couple of psychoanalysts in, to assess the character's mental health; they concluded Medea "had borderline personality disorder, and issues with projection".

"Medea is just a perfect study of what happens to the mind under pressure," says Power. "Euripides describes the stages of grief in a way which took until the 20th century to be articulated theoretically – it's just there, embedded in the drama. I'm fascinated by the way a really contemporary psychology is located within something ancient and epic and mythic: that feels really potent." µ

'Medea', National Theatre, London SE1 (nationaltheatre.org.uk) 14 July to 4 September; part of the Travelex £15 season

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments