Chevalier de Saint-Georges: The man who got under Mozart's skin

Was Chevalier de Saint-Georges, ‘the Black Mozart’ and the composer’s nemesis, the inspiration for The Magic Flute’s most villainous character

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Opera stories generally require suspension of disbelief. But even so Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute) presents more than its fair share of problems, despite the beauty of its music. One of the most unpalatable is a villainous character named Monostatos – who is black.

First he is the wise Sarastro’s servant, and enemy of our hero Tamino, who seeks to rescue the evil Queen of the Night’s daughter, Pamina; then he attempts to rape Pamina; finally he swears allegiance to the Queen, who promises him Pamina as reward. Most productions today (including English National Opera’s staging by Simon McBurney, being revived in February) quietly circumvent Monostatos’s stipulated colour. But why did Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and his librettist, Emanuel Schikaneder, create a black character at all?

Though encountering other races was not exactly an everyday occurrence in 18th-century Vienna, Mozart had come across one particular individual of Afro-Caribbean background years earlier, in a context that makes the motivation behind Monostatos distinctly intriguing.

In 1778, aged 22, Mozart went to Paris, with his mother, Maria Anna, to try to establish a career there. His six-month stay was both a disaster and a tragedy. French musical life revolved around the royal court. Louis XVI had assumed the throne in 1774 and music was among Queen Marie Antoinette’s chief pleasures. Mozart had met her in 1762 when he was a six-year-old prodigy performing for the court at Vienna’s Schönbrunn Palace and she was Princess Maria Antonia, daughter of the Habsburg Empress Maria Theresa and the Holy Roman Emperor Francis I. Mozart, the story goes, slipped on the wooden floor; the little princess, aged seven, helped him up. He gave her a kiss, saying he’d like to marry her.

Breaking into French society as an adult musician was another matter. Mozart loathed Paris. He found the French “frightfully arrogant”, was “appalled by their general immorality” and felt “they understand nothing about music”.

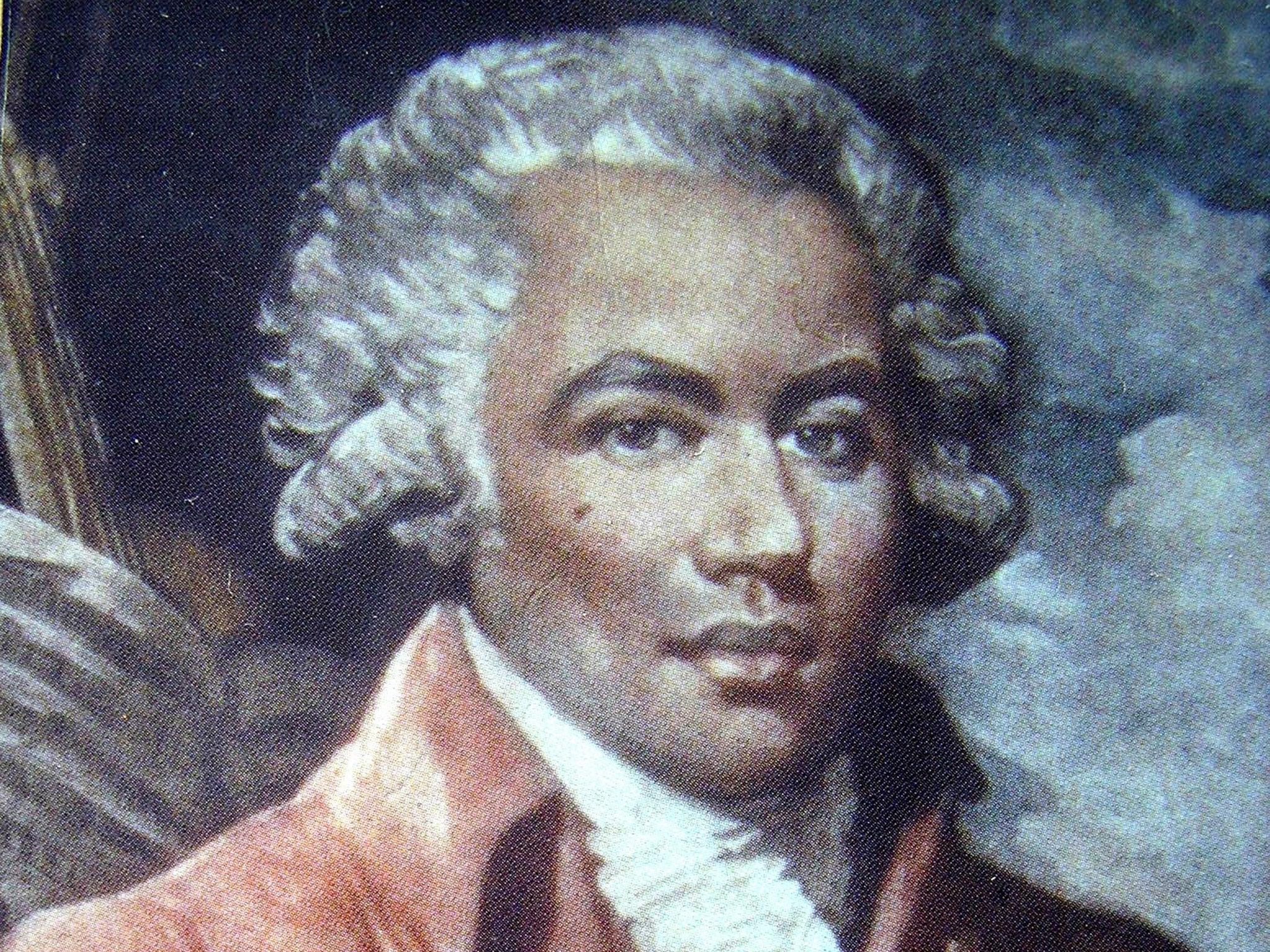

One musician numbered among Marie Antoinette’s closer acolytes as her music teacher. Eleven years Mozart’s senior, he was a local celebrity both as a musician – violinist and composer – and as a swordsman. His name was Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges (1745-1799), and he was a “mulatto”, the illegitimate son of a Guadeloupe plantation owner and an African slave girl. His father, George Bologne de Saint-Georges, had brought the boy to Paris and made sure he received the finest education. The Chevalier de Saint-Georges is often termed “the black Mozart” (as in Chi-chi Nwanoku’s Radio 4 documentary, In Search of the Black Mozart) and the US president John Adams judged him “the most accomplished man in Europe”.

He shared with Mozart one important contact: the Baron von Grimm, writer, diplomat and secretary to the Duke of Orleans. Grimm had been astounded by the prodigy Mozart when the musical family from Salzburg visited Paris in 1763; therefore when Mozart and his mother arrived in 1778, Grimm was keen to serve as his manager and mentor.

But in July Mozart’s mother, Maria Anna, fell ill and died. Grimm was living in the ducal palace and now he took the distraught young composer in to stay with him. Another resident at the palace was none other than the Chevalier.

So, while Mozart was at rock bottom – mourning, lonely, fighting the language and finding promised payments for commissions failing to materialise – he would have encountered, under the same roof, Saint-Georges, who at 33 was exotic, brilliant, established, at ease, popular with the ladies and close to the Queen. Everything Mozart was not. Moreover, he led one of the best orchestras in Europe – Le Concert des Amateurs – while Mozart’s symphonies received inferior performances at the Concert Spirituel. Mozart had every reason to be jealous of this gifted and successful “mulatto” colleague, and within the racist society of their day.

The libretto of Die Zauberflöte, of course, is not by Mozart, but by Schikaneder, written in 1791. Why would Schikaneder take what could be a sideswipe at Saint-Georges by creating Monostatos, the lustful sidekick of an evil Queen? Well, opera is usually collaborative. The high-spirited Mozart and the theatrical entrepreneur, writer and actor Schikaneder had been friends since 1780, barely two years after Mozart’s Paris sojourn.

Ultimately Monostatos and the Queen of the Night are mysteriously destroyed. By the time Die Zauberflöte was premiered in September 1791, the French monarchy was assuredly under threat. That December, Mozart died. The following September, the National Convention in France established a Republic. Marie Antoinette was guillotined in September 1793.

Saint-Georges’ story came to a premature end, if less so than Mozart’s own. After surviving the French Revolution, if by the skin of his teeth – for he was imprisoned and threatened with execution – and having returned from military adventures in Saint-Domingue, the Chevalier found himself living in semi-retirement and shattered health in Paris, where he tried to re-establish an orchestra. “Towards the end of my life, I was particularly devoted to my violin,” he said. “Never before did I play it so well.” He died aged 53, having given his last few years to his music.

Short of a treasure-trove of unknown Mozart letters turning up, though, we will probably never know whether Monostatos really might be Mozart’s revenge upon Paris, served ice-cold.

‘The Magic Flute’ is in rep at Coliseum, London WC2 to 19 March (020 7845 9300)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments