Cameron Douglas on his drug-fuelled descent from a luxury upbringing to seven years in prison

The third generation of one of Hollywood’s most famous dynasties, Cameron Douglas suffered a drug addiction that landed him a lengthy prison sentence, writes Dave Itzkoff

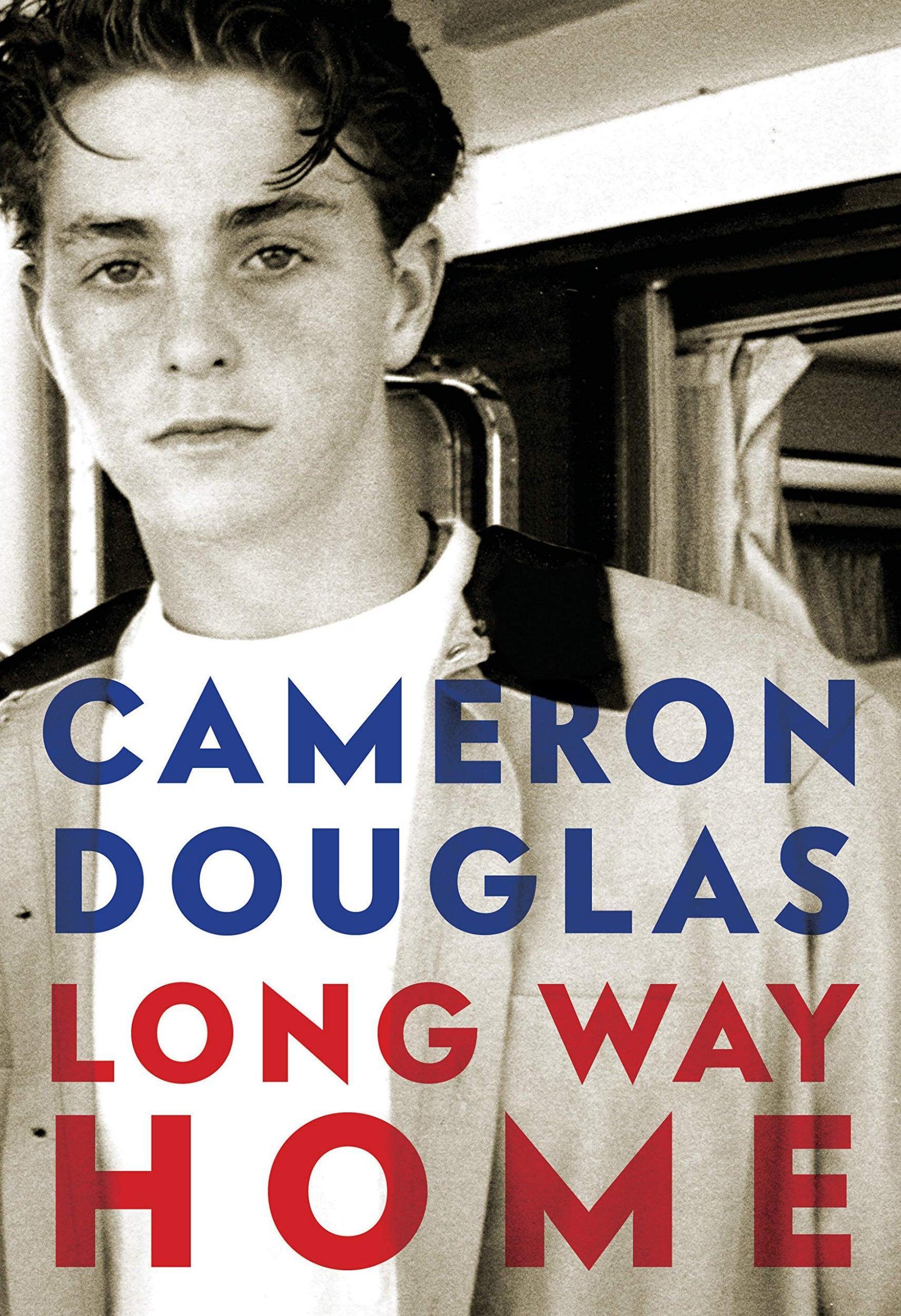

When Cameron Douglas was arrested at a New York hotel in 2009 for possession of crystal meth, he was given a choice. As he recounts in his memoir, Long Way Home, a drug enforcement administration agent told him that he could either be taken out the front door, kicking and screaming, or, “for your family’s sake, we can take you out the back way, put you in a car.”

Even after having served almost eight years in prison for possessing heroin and selling drugs, Cameron’s family remains prominent in his life, and the subject of family permeates his book.

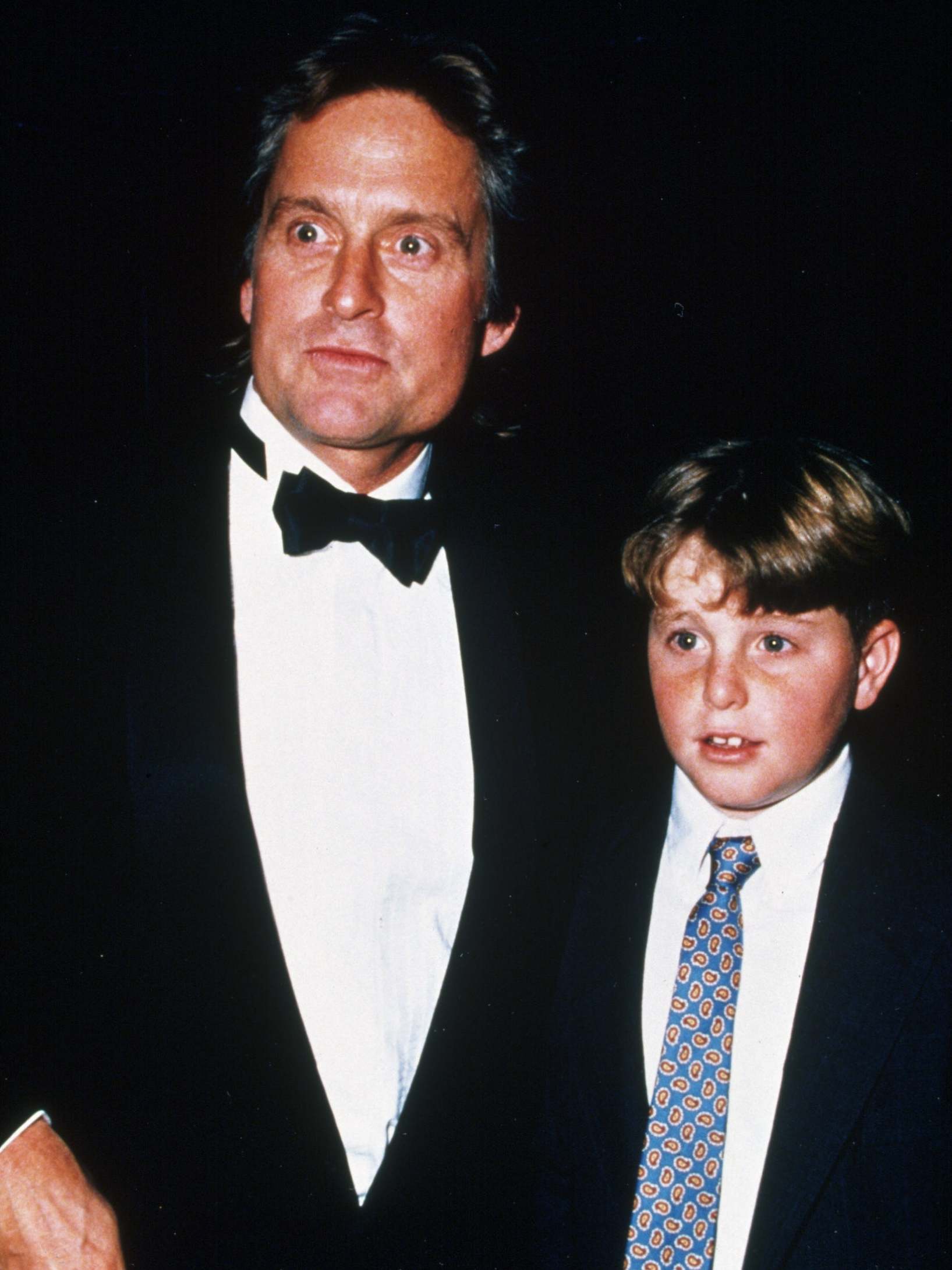

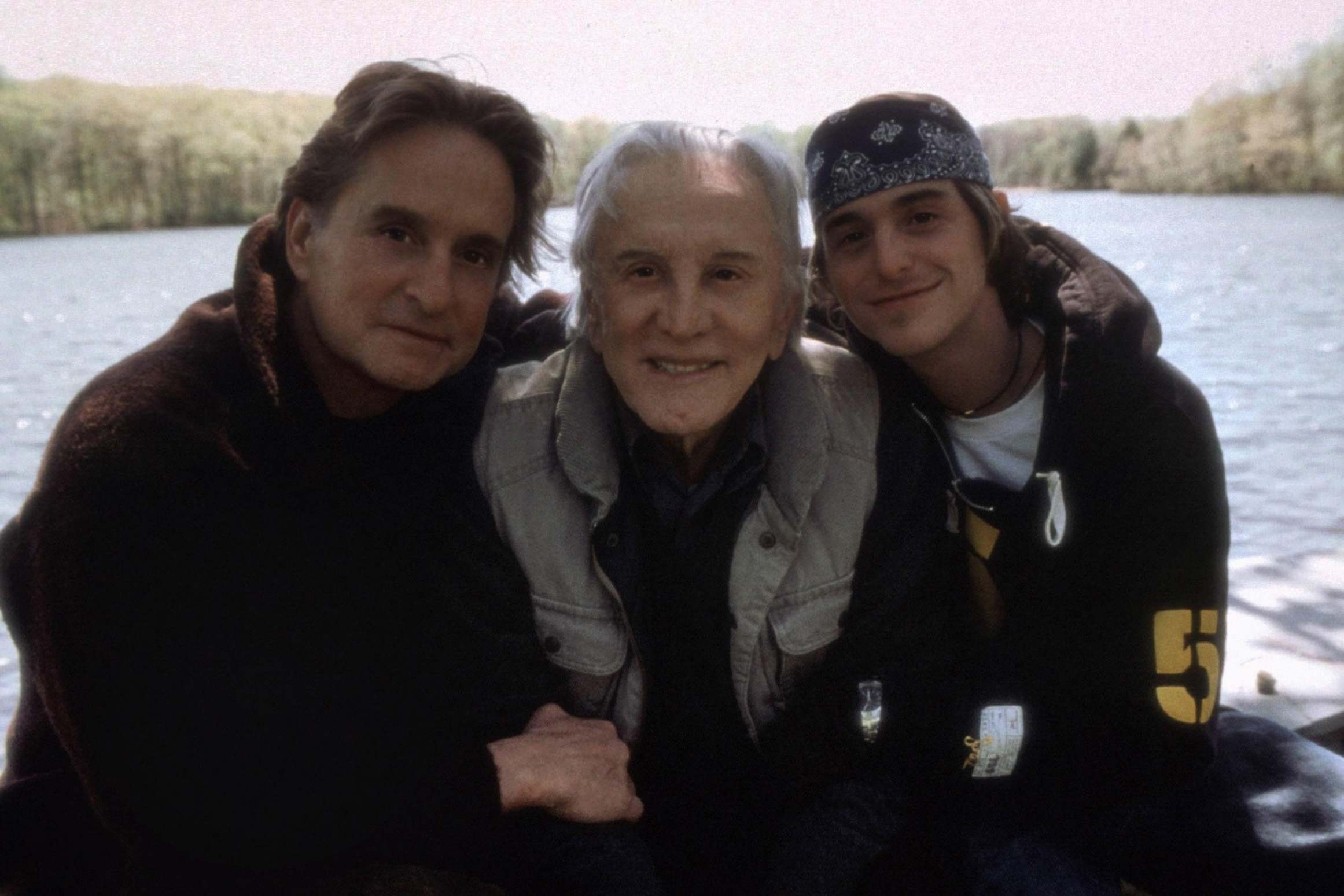

He is the oldest son of Michael Douglas, the Academy Award-winning actor and producer, and a grandson of Kirk Douglas, the venerated Spartacus star. While the thought of living up to either one of their reputations could seem paralysing, Cameron is adamant that he does not expect anyone’s sympathy for squandering his privileged upbringing.

He’s also clear that he does not blame the burden of his surname for sinking him into a mire of hard drugs, crime and punishment. “There was nothing anybody could do to get through to me at a certain point,” he says. His voice is tentative, and despite having he has been a free man since 2016, he speaks like someone still adjusting to seeing daylight on a regular basis.

Cameron takes a breath and continues, “All those years that the book is based on, all the pain and destruction that a lot of my behaviour caused, is done. I can’t go back and undo that.” But he hopes that by sharing his experiences and ruinous decisions “other people won’t have to make them”.

Long Way Home is Cameron’s unsparing account of how he pursued what he calls his “demented death wish”, chasing addictions to heroin and liquid cocaine, shaking off rehabs and forcible interventions, and nearly getting himself killed numerous times before turning to drug dealing to support his habit.

And that’s just part one. Part two focuses on Cameron’s arrest, indictment and incarceration, during which he was shuttled among a half-dozen federal penitentiaries and spent nearly two years in solitary confinement.

In telling his story, Cameron cannot avoid shining a spotlight on his illustrious if enigmatic family. Writing with the same scrutiny he applies to himself, Cameron tells of his exasperated father, Michael, his press-shy mother, Diandra (who divorced Michael in 2000), and the combative generational dynamics that came with the Douglas name.

Yet both Michael and Diandra say that they understand that their son needed to write the book to make sense of his struggles and to keep him focused. And Cameron in turn recognises the sacrifices that his parents made in letting him do it. “Allowing me to tell my story, which inevitably is connected to my family, it’s a very selfless act,” he says. “It’s like the ultimate way of saying I love you.”

Allowing me to tell my story, which inevitably is connected to my family, it’s a very selfless act. It’s like the ultimate way of saying I love you

Cameron is 40, with a quiff of reddish-brown hair and his father’s distinctively narrow facial features. When we meet, he is dressed in a long-sleeved T-shirt that covers an assortment of tattoos across his chest, and wears a wristband held together by a charm shaped like a ship’s anchor. “To me they represent the explorer – a man’s man,” he explains. “Somebody that’s travelled and been through some stuff.”

As he recounts in Long Way Home, Cameron, too, has been to some places and seen some things: the lavish homes in New York and Santa Barbara, California, where he grew up; the elite private schools that admitted and later expelled him; the fountain where he crashed a sport utility vehicle after snorting crank and fleeing a secret service agent; the liquor stores and motels he stuck up as much for the illicit thrills as for the money; and the prison cells where he watched inmates fight each other with padlocks attached to shoelaces.

But the author is not the only one on display. He writes tenderly of how his parents met in 1977, when Michael was 32 and Diandra 19, and married eight weeks later. He describes a childhood populated by his father’s celebrity pals – Jack Nicholson, Pat Riley, Danny De Vito – and he has fond memories of seeing “beautiful grown-ups doing the things that beautiful grown-ups living lives of excess do.”

This euphoria soon dissipated. Cameron’s mother threatened to end the marriage in the mid-1980s, after learning that his father was having “a fling” with Kathleen Turner, his Romancing the Stone co-star. In the early Nineties, having been caught in another act of infidelity, his father checked into an Arizona clinic for drug and alcohol treatment. Finally, in 1995, when a private detective hired by his mother returned with surveillance photos of his father in a hotel with another woman, his parents separated for good.

Growing up, Cameron was acutely aware of the conflicts between his father and his grandfather: Michael was determined to stand outside his father’s shadow, and Kirk resented Michael for replacing him with Nicholson in the film version of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest – which Michael produced, and which Kirk had starred in during its original Broadway run.

Similar tensions emerged in Cameron’s relationship with Michael, and the pair even physically fought on occasion. Cameron worshipped his father but resented having to share him with his many fans. As he writes in the book, “Every son admires his own father, but everyone in the world admired mine.”

I thought in telling the story it might make him understand what the hell happened and where it all went

This estrangement only worsened through Cameron’s years of drug use, when he felt that his father was pulling away. “A lot of the anger that I felt was really towards myself, because I was failing at making him proud of me,” he says. Michael, whose half-brother Eric died of an accidental drug and alcohol overdose in 2004, has admitted that he had resigned himself to the belief that Cameron would meet a similar fate, saying: I thought I lost him a couple times over those years.”

Yet it was his father who encouraged Cameron to write a memoir, even before he was released from prison. “I thought in telling the story, if he was able to make a book deal, it might make him really try to understand what the hell happened and where it all went,” Michael explains.

During his incarceration, Cameron kept journals and wrote poetry as a kind of mental regimen to get himself through each day. After his release, he began collaborating with Benjamin Wallace, the author and journalist, to write what would eventually become Long Way Home.

Douglas recognises that “99.5 per cent of the people don’t have the opportunities that I had when I came home,” feeling that these advantages obliged him to do something meaningful. The book gave him a sense of purpose as he readjusted to life on the outside. “It was something I was clinging to,” he says, “something solid that I could count on, that was productive and people seemed to be interested in.”

Throughout the book, Cameron tries to be candid about moments he cannot completely recall, when his memories have been rendered unreliable by time and addiction. (There are also the usual contradictions in the historical record: to this day, his mother and father continue to disagree about whether Cameron was allowed to see Basic Instinct when he was 13.)

While Michael admits to having taken issue with a few parts of Cameron’s early drafts of the book – and even having said “Excuse me, au contraire” – he was, on the whole, impressed.

“It was not a book that was solely based on how his parents let him down,” Michael explains. “There’s always going to be an element of criticism, which I certainly accept and understand. But no, it wasn’t combative.”

He adds that he and his family were accustomed to being on display, saying: “You learn how to balance between that public exposure and maintaining your own privacy.”

Diandra, on the other hand, admits to having found the book difficult to read, having already lived through its harrowing details. “If I told you all the rehabs I’ve been to, and court hearings and visitations and driving 950 miles every other weekend to prisons, it’s really consumed, I would say, a large portion of my life for 24 years.”

Although she says that Cameron did not specifically seek her approval before writing the memoir – “I think it was really Michael and Cameron that decided they were going to write this book” – she says she “tried to be as supportive as possible”.

Despite having read parts of an earlier manuscript, Diandra did not know “the ultimate outcome” of the book. Yet even after being told that Long Way Home discussed intimate details of her marriage to Michael and its dissolution, she expressed confidence that Cameron would strike the right tone. “As a human being, placing blame is very easy,” she says. “Taking responsibility for one’s actions is a lot tougher.”

Since his release, Cameron has moved back to Los Angeles, where he lives with his girlfriend, actress Viviane Thibes, and their daughter. He is pursuing an acting career and plugging away at some screenwriting projects, as well as having occasional breakfasts with Kirk, who lives nearby, and volunteering at a homeless shelter.

If his days feel overdetermined, it is a sensation that he much prefers to prison, where he had nothing but time and few opportunities to use it as he wished. “I used to say to myself, how does anybody get anything accomplished, out in the real world, in such a short amount of time?” he says. “I can barely get these four things done.”

Beyond the family that he has built for himself, Cameron’s principal responsibility is establishing a track record of diligence and consistency, so that his name will mean something aside from his past crimes – a task that he faces with optimism, despite knowing that it would be a slow process.

“A lot of it is digging myself out of this hole and proving to people that I’m reliable,” he says. “Once some people start to see that, then the rest will follow suit.”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments