We translated the Marquis de Sade's most obscene work – here's how

When translating The 120 Days of Sodom, we had a duty to be just as rude, crude, and revolting as Sade

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.

Warning: contains rude words. Excuse my French. And English.

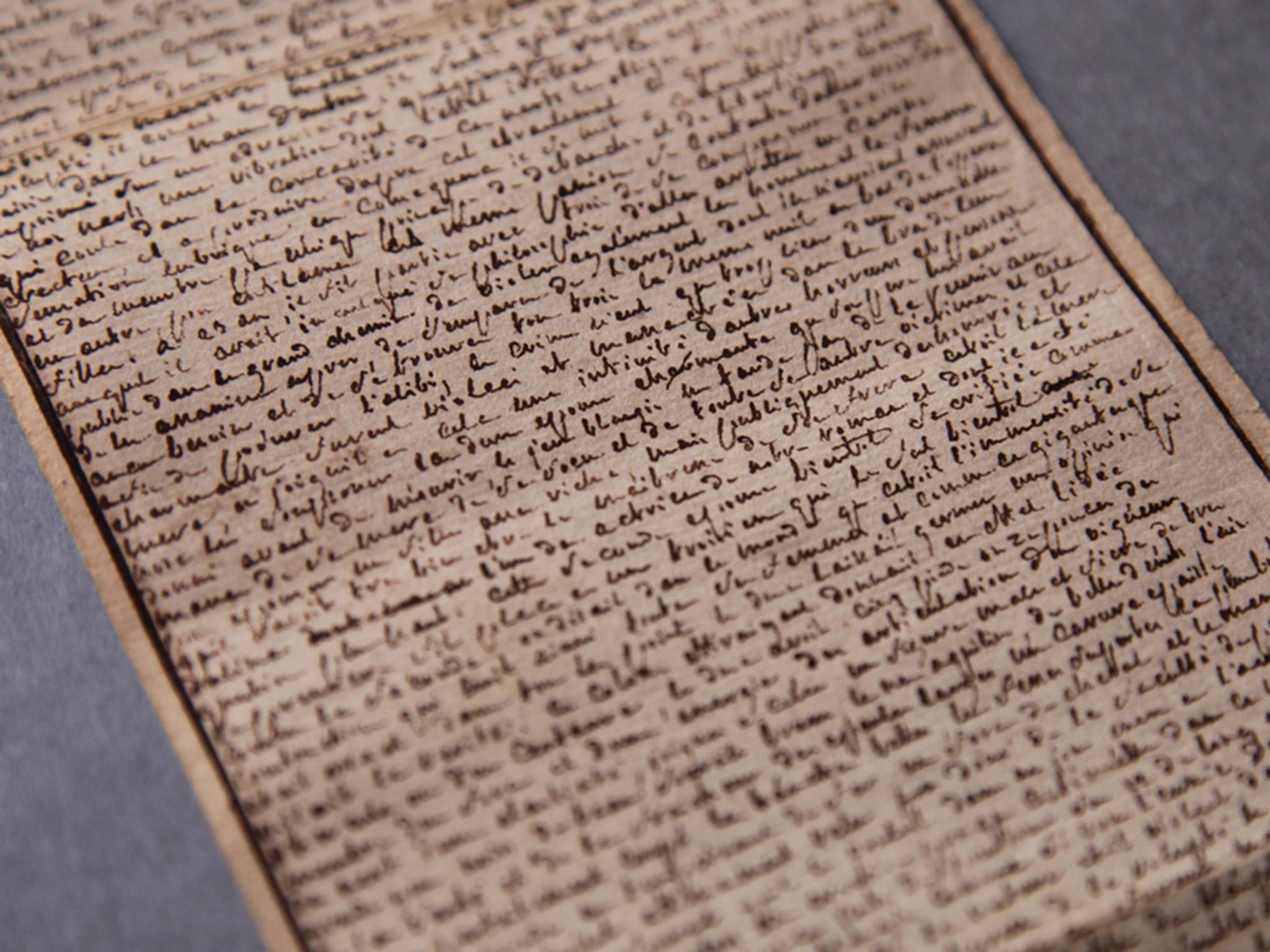

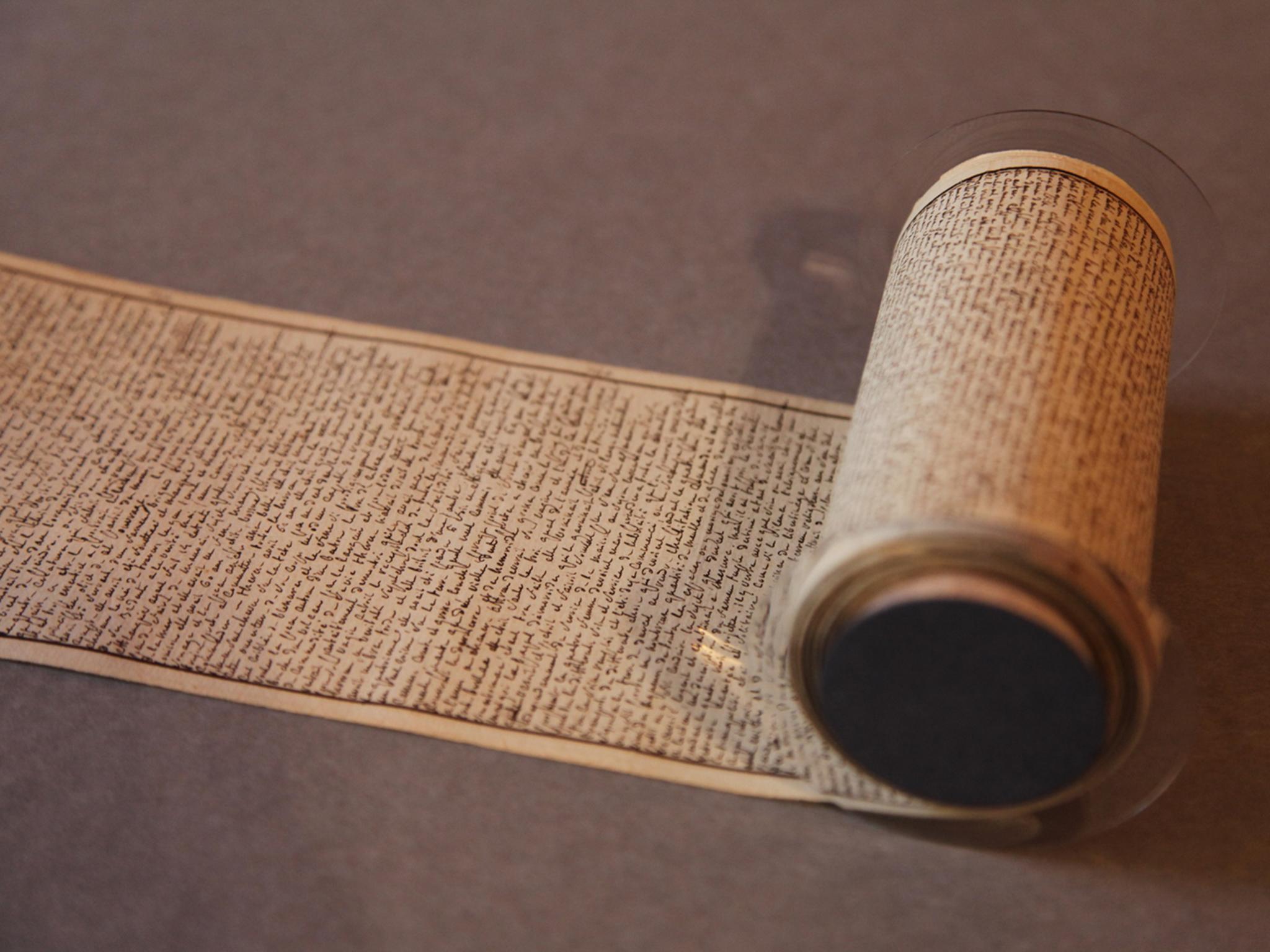

The Marquis de Sade’s earliest work of fiction, The 120 Days of Sodom, is also his most extreme. It tells the story of four libertines – a duke, a bishop, a judge and a banker – who lock themselves away in a castle with an entourage that includes two harems of teenage boys and girls. Four ageing prostitutes, appointed as storytellers, each tell of 150 “passions” or perversions over the course of a month. The libertines enact the passions they hear described, and as these become more violent, the narrative builds to a murderous climax. Though Sade never finished his novel, and the last three parts are in note form only, it remains a uniquely disturbing work.

And therefore uniquely challenging to translate. Perhaps this was the reason no one had attempted a new translation since the one first published by Austryn Wainhouse in 1954 (and revised with Richard Seaver in 1966). In any case, Thomas Wynn and I felt a new version was long overdue, and, much to our surprise, Penguin Classics agreed.

Dealing with the violence was not the only challenge we faced: The 120 Days is also Sade’s most obscene work of fiction. Over the course of three years, this indeed was the issue that prompted the most discussion and debate between us. How exactly were we to translate the various rude words of the original French? Was a vit a prick, dick or a cock? Were tétons boobs, tits or breasts? Was a derrière a behind, a backside or, indeed, a derrière? Was a cul a bum or an arse? While Wainhouse adopted an eccentric idiom that could be best described as mock-Tudor, we decided to try as far as possible to use sexual slang that was still in use today – as long as it did not sound gratingly contemporary.

Translating obscenity into your own language takes some getting used to. However familiar one becomes with another language, a trace of otherness always remains. Sometimes this can add to the beauty of the language, or to its mystique, but when it comes to obscenity there is a distinct softening effect. Rude words in other languages never have quite the same force, so translating them into one’s own language brings the obscenity home in more ways than one.

English reserve probably plays a part in the process, too. When we started translating 120 Days I soon realised I was instinctively toning the original down, avoiding words that I found jarringly ugly. I may not have overcome that entirely (no dicks or cocks for me, thank you very much!) but I realised pretty quickly that a watered-down version of Sade’s novel would be the worst possible outcome. The last thing we wanted to produce was a text that was any less shocking – and therefore potentially appealing – than the original. We had a duty to be just as rude, crude, and revolting as Sade.

To ensure consistency we compiled our own Sadean lexicon as we were translating. Once we had debated the various possible translations of a particular word we would try to settle on one and stick to it. Usually. So a vit would always be a prick, and a cul would always be an arse.

But this wasn’t always possible. When it came to translating tétons, for example, one word was not enough. One of our most treasured resources as translators was the University of Chicago’s database of old French dictionaries, which includes several from the 17th and 18th centuries.

One of the things this showed was that téton was not always quite as familiar or coarse as the English “tit” (Molière and Voltaire both used it), so we had to be attentive to these different inflections. In cases like these, it matters whether the word is written by the narrator or spoken by one of the characters, whether it is said by a man or a woman, neutrally or insultingly, and so on – a man or woman writing “breasts” is very different to a man saying “tits” and very different to a woman saying “boobs”.

The term that gave us the most trouble by far was the verb se branler – a slang term meaning to masturbate that is still commonly used by French speakers today. There may be no shortage of English equivalents, but nor is there any shortage of Englishes to consider – and therein lies the problem. The most obvious English equivalent – “to wank” – would be unfamiliar and odd on one side of the Atlantic, while “to jerk off” would be familiar but decidedly American in its associations to English readers. We contemplated “to pleasure oneself” but it seemed a little sex-positive and a little too polite, while “fapping” had yet to hit the public (or our) consciousness.

Ultimately, we decided on “to frig” even though we were aware that this use of the word would be unfamiliar to many readers – particularly those too young to remember the Sex Pistols’ version of Friggin’ in the Riggin’ (1979). When we canvassed our students, most thought “frig” was a euphemism for “fuck”; and indeed most dictionaries now give “have sexual intercourse with” as the first definition, and “to masturbate” as the second.

But “to frig” works in a way that the alternatives do not – it is compact, and usable reflexively or non-reflexively, and transitively or intransitively. We think – or hope – its general unfamiliarity might work in its favour for many readers, as this will mean it won’t have strong associations of one particular form of English. In any case, as it occurs so frequently in our translation, we hope readers will soon get used to it and that its initial strangeness will soon be forgotten.

Who knows – perhaps the legacy of this translation will be a return of frigging?

Sade’s The 120 Days of Sodom, translated by Will McMorran and Thomas Wynn, was published earlier this month as a Penguin Classic in the UK. It will be released in North America on December 27 2016.

This article was originally published on The Conversation (www.conversation.com) Will McMorran is a Senior Lecturer in French & Comparative Literature at Queen Mary University of London

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments