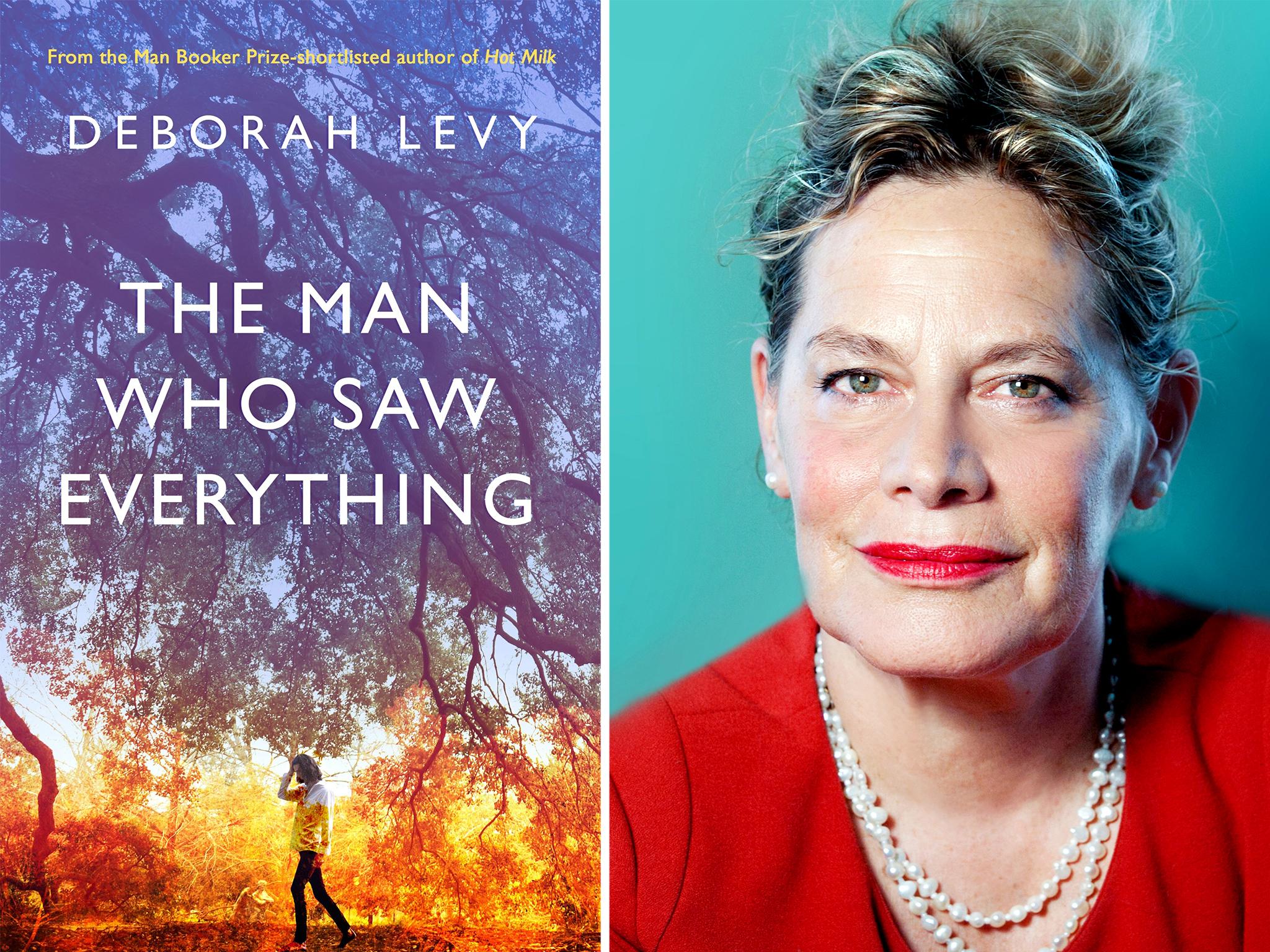

The Man Who Saw Everything by Deborah Levy, review: A Rubik’s cube of a book

As the past and the present mix, so too does socialism and sexuality

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was 50 years ago this month that The Beatles were photographed on the zebra crossing on Abbey Road. Deborah Levy’s new novel opens in September 1988, when Saul Adler tries to cross that same zebra crossing. In July 2016, he tries again. It is possible he gets hit by a car both times. Fitting together exactly what you’ve seen isn’t always easy in this greased Rubik’s cube of a book.

The Man Who Saw Everything looks at the power of a photograph to capture a moment in time, or to capture a person. It’s about how we see – or fail to see – ourselves and others, with eyes and camera lenses and state surveillance. It’s also about how we “see” the past alongside – or rather, in among – our present. The opposite, really, of a photograph, which fixes a single instant in time.

In 1988, in the first half of Levy’s novel, the 28-year-old Saul – our narrator, a beautiful historian with piercing blue eyes – continues, bleeding, to visit his photographer girlfriend Jennifer Moreau, who’s forbidden him from describing her own beauty. Both lost their mothers when they were young (just like John Lennon and Paul McCartney). We hear that Jennifer likes the opening line of The Communist Manifesto, about communism as a “spectre haunting Europe”, and that she thinks there’s a spectre inside every photograph too. Both ideas certainly go on to haunt the book.

Saul’s father has recently also died. He was a socialist who wanted his ashes buried in the GDR, and he was cruel to his pearl-wearing, academic, bisexual son. Saul is writing a paper linking the tyranny of fathers with the tyranny of dictators: Stalin was both bullied by his father, and bullied his children.

Saul and Jennifer have sex, Saul proposes, and Jennifer dumps him, accusing him of taking too little interest in her art. Saul pays less attention to her intentions than her subject – which is him. He is, he believes, her muse.

Licking his wounds, Saul goes on a research trip to the GDR. He forgets to take a tin of promised pineapple; the family he stays with in Berlin turn out to be distraught by this act of thoughtlessness, which in its own way motors a series of life-changing events.

Saul’s translator is the confident, vital Walter Müller. And Walter can’t stop looking at Saul – both as a man he’s falling in love with, and as a spy, an agent of his authoritarian fatherland. Meanwhile Walter’s sister, Luna – a highly strung dancer who loves The Beatles and is desperate to escape – makes her own advances on Saul.

All of which – even as a bald plot summary – sounds ripe and rich, right? And it is: Levy, twice shortlisted for the Booker for Swimming Home and Hot Milk, is writing with gorgeous, juicy assurance here. It’s stylish: written with a speedy, vivid economy, her characters’ eccentricities leaping off the page. It’s funny: Saul’s narcissistic narration is full of deadpan details of youthful pretentiousness, social awkwardness. It’s sexy: Levy writes keenly about layered attraction and resentment, how her characters bestow and withdraw gifts of sex and affection. And it’s political: the novel exposes the hypocrisies that accompany rigid ideology, but also questions how an individual can live with integrity if they only live for themselves.

There’s also all sorts of other stuff going on in the first half, however – stuff that it’s basically impossible to get a handle on. Strange interjections. Unexplained names. Saul somehow knows exactly when the Berlin Wall will fall. Images “from another geography, another time” interrupt.

It’s also impossible to review the rest of the book without spoilers, so fair warning. But if the first half can feel like a puzzle you’re getting nowhere with, initially I was disappointed with the solution: Saul’s been in a bad accident on Abbey Road, and the second half takes place in hospital. Blame morphine; blame injury. His past is not only muddled up in his present in 2016, but we realise that the first half was his memory of 1988, as corrupted by the present. His spectres working overtime.

Sunflowers and jaguars and a toy train appear across both halves, in different contexts. A Stasi agent in 1988 turns into a benign nurse in 2016. It’s perilously close to “he woke up and it was all a dream”. Or it would be if Levy’s writing wasn’t so damn good, if her constantly turn-over-able narrative didn’t keep developing to the last. And with it, so develops the reader’s image of Saul Adler.

It’s only towards the end of The Man Who Saw Everything, when many different memories come clearly into view, that we see all of his carelessness and selfishness, and all the ways his careless and selfish choices have impacted on other people. It is only when we see Saul through the eyes of others – through a different lens, if you like – that we finally see everything.

The Man Who Saw Everything is published by Hamish Hamilton, £14.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments