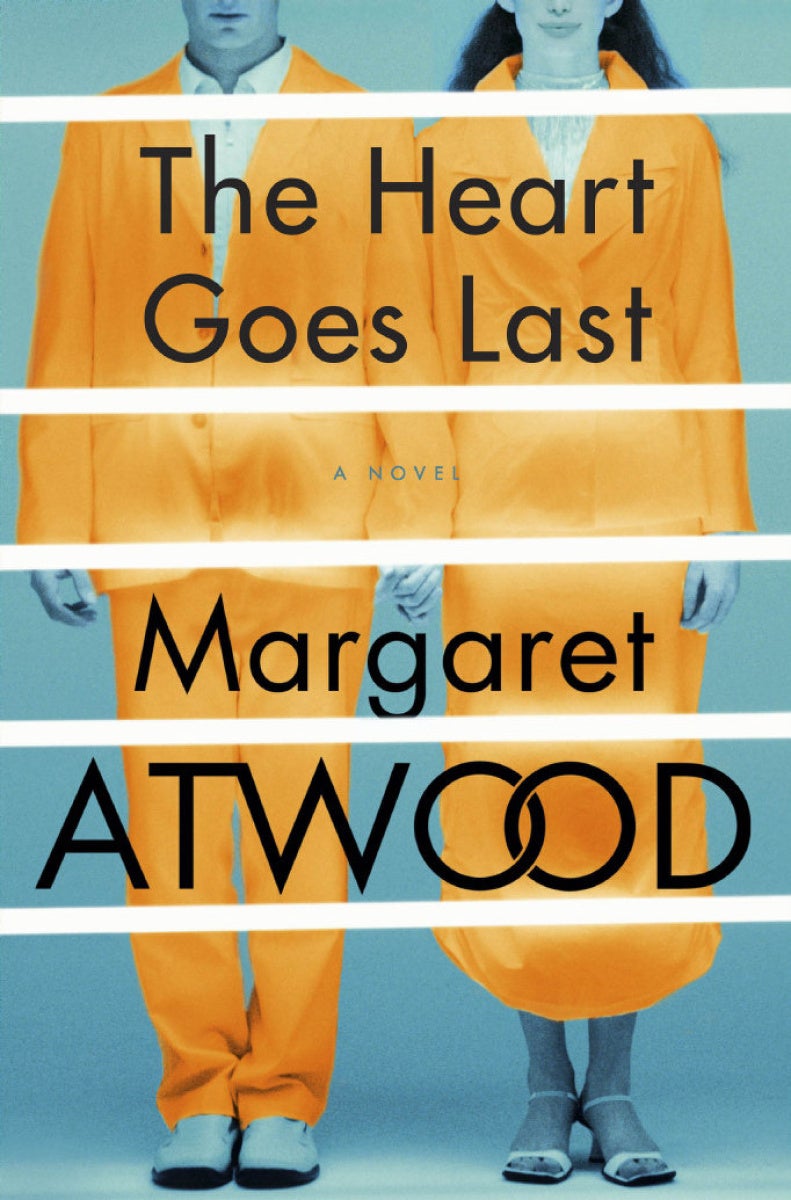

The Heart Goes Last, by Margaret Atwood - book review: Travels in Dystopia, with Doris Day and Marilyn

Bloomsbury - £18.99

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Throughout her lengthy career, Margaret Atwood has challenged the way we think about the interactions between humans and technology, and explored the implications that that might have on society. This latest novel is a stand-alone piece of typical speculative fiction, and it deals with a lot of the same ideas as Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy, as well as looking at elements of free will that echo many of her earlier works.

The premise is an intriguing one, though I’m not convinced that Atwood builds on it as well as she might have. In a post-economic meltdown United States, Stan and Charmaine have fallen on hard times just like millions of others. They have lost their jobs and their home and are living in their car and eating scavenged scraps, terrified of roving gangs in the lawless and dangerous streets.

This dystopian world is rather sketchily drawn out, and appears only to apply to parts of the country, as later on there are a number of references to more affluent regions. But anyway, in a bid to escape their dire circumstances Stan and Charmaine sign up for something called the Positron Project. The company that runs the project has built a nice, clean retro town called Consilience and applicants are given a lovely house and cushy new jobs. The catch is that they only live in the house on alternate months, and spend the rest of their time in the Positron prison, swapping with “Alternates” who then move into the house for a month. It’s a neat idea, and to begin with the reader is led to think there might be echoes of the famous Stanford University experiment in which ordinary people role-playing as prison guards began abusing their role-playing prisoners.

Life in Consilience is heavily controlled, with bugging and monitoring rife, and no communication with the outside world is allowed. The town is built on the model of a 1950s ideal, with white picket fences everywhere and Doris Day constantly on the wireless, reminding me more than a little of the eerie feel of The Truman Show.

Initially, Stan and Charmaine love their new life, and their time in prison isn’t particularly arduous, because their jail mates aren’t real criminals either. But of course, things start to unravel. Both Stan and Charmaine begin to entertain sexual fantasies about their Alternates, the people sleeping in their bed when they’re not there, and when they act on those fantasies, their worlds quickly fall apart.

It’s around this time that The Heart Goes Last rather loses its way. For the first part of the novel Atwood wants to make us connect emotionally with Stan and Charmaine’s plight and their desires. But as the plot progresses it becomes increasingly more slapstick, and Atwood herself seems to stop taking things seriously, which rather diminishes the reader’s engagement.

There are plenty of sinister elements later on, with the people in charge of Consilience using their high levels of social control for much more nefarious activities than are apparent on the surface, but it’s all treated too flippantly.

Charmaine is given an interesting storyline where her job in the hospital cleverly demonstrates how we can be led into doing things that our normal morality wouldn’t allow, simply with the right encouragement. If you do bad things, but you’re told it’s for good reasons, does that make you a moral person?

Similarly, towards the end Atwood addresses some neat ideas about how much control we really want over our own actions and minds. Given the option to be reprogrammed as contented and happy, should we take it? Or are we better off sticking to who we are, faults and all?

But between these glimmers of thought-provoking stuff there is quite a lot of nonsense. A plot to get information out of Consilience and expose what the company is doing is a badly thrown-together romp, with prostitute robots, Elvis and Marilyn impersonators and mind-altering laser surgery. And I never fully bought the outlandish things that the people in charge of Consilience were supposed to be doing. Not that people in power don’t abuse that power to do awful things, but rather the jokey tone with which Atwood addressed the matter tended to jar with the issues at hand.

The plotting elements in the last act also fall flat, with too much reliance on unbelievable coincidence, and the whole thing is resolved far too easily after a somewhat laborious build up.

All of which is a shame, because the author’s central ideas are, as always with Atwood, fascinating. What does it really mean to love someone? How much free will do we really have in matters of the heart? What would we do for safety and security? I just wish The Heart Goes Last tackled these ideas with more conviction.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments