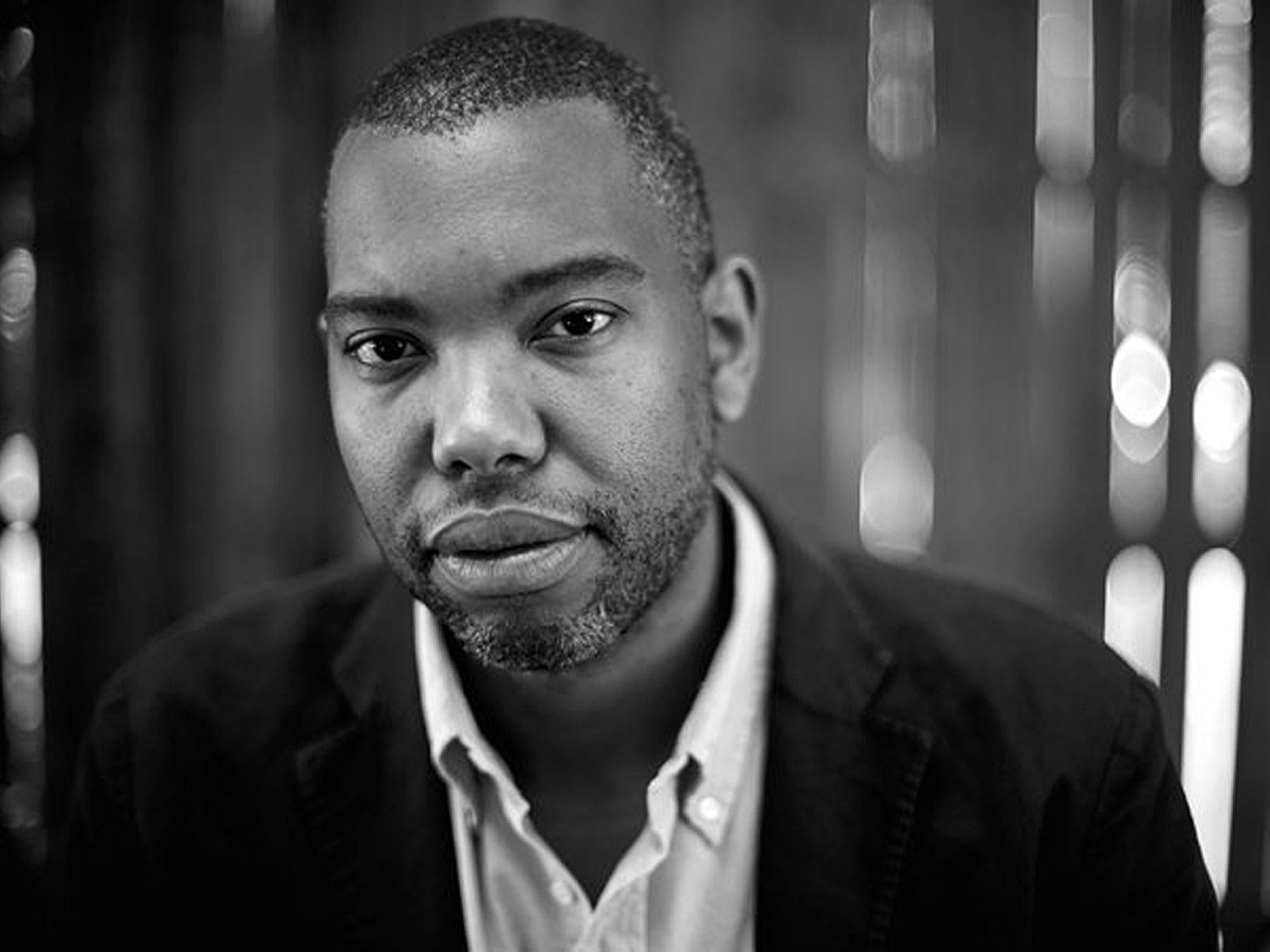

Ta-Nehisi Coates and the making of a public intellectual

Coates has become one of the most influential black intellectuals of his generation

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Ta-Nehisi Coates’ first book The Beautiful Struggle was published in 2008, it landed with barely a ripple. At the time, Coates was a struggling writer. He had lost three jobs, and he and his family relied on unemployment checks, his wife’s income and occasional support from his father to stay afloat. By the time the book came out in paperback, his fortune had shifted slightly; he’d become a regular contributor to The Atlantic magazine, writing a blog that attracted a moderate but engaged audience.

“I went and did a few events. I did one in Brooklyn and I did one in San Francisco, and maybe 30 people showed up. And I thought, ‘This is what I want. This is it,’” he said in a conversation over a recent lunch.

Suffice it to say that Coates’ second book, Between the World and Me, published in 2015, did not suffer the same lack of readership. An early proof was sent to Toni Morrison, who strongly endorsed the book, calling it “required reading” and likening Coates to James Baldwin. That year, Coates was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship and the National Book Award in nonfiction. His appearances filled auditoriums and the book was adopted on college syllabuses. It has sold 1.5 million copies internationally and has been translated into 19 languages, catapulting him to prominence.

At the age of 41 (he turns 42 on today), Coates has become one of the most influential black intellectuals of his generation, joining predecessors including Morrison, Professor Henry Louis Gates Jr, and Cornel West. “He’s a rock star,” said Nell Irvin Painter, professor emeritus of American history at Princeton University, adding that Coates is asking questions that even “other historians have not been asking”.

His new book, We Were Eight Years in Power: An American Tragedy, traces his ascent. In it, he collects articles he wrote for The Atlantic during Barack Obama’s presidency, interspersing them with explanatory, autobiographical essays. The book goes on sale on Tuesday and already, his book-tour stop at Brooklyn’s Kings Theatre has sold out – a far cry from the intimate crowds of his early career.

In the beginning of September, about a month before his book was to be published, Coates gave a preliminary reading at BLVD Bistro, a soul-food restaurant in Harlem tucked into the ground floor of a brown sandstone building with preserved old-school features like brick walls and a tin ceiling. He stood at the head of the room, in front of a large wall decal of James Baldwin’s face lined with the words: “Our crown has already been bought and paid for. All we have to do is wear it.” He wore a white button-down shirt, jeans and blue and white Nike sneakers.

The event was brimming with people close to Coates: his wife, son and mother; the New York writer Jelani Cobb; Barry Jenkins, the director of Moonlight; and Painter, among others. Coates was comfortable and relaxed, joking once about the rap music that blasted in through the windows as a car drove by (“That’s so appropriate, being upstaged by Kendrick.”). He seemed, in that moment, perfectly settled in between the intellectualism and hip-hop that influenced him, freed from, as he describes in We Were Eight Years, “those young years trapped between the schools and the streets”.

When the discussion was opened up to the audience, Jenkins asked how Coates advised his son on the subject of political activism. Coates answered that his own father had been part of the Black Panther Party and had later become disillusioned with mass politics. Coates’ advice to his son, Samori, was to educate himself before getting involved in protests. “I don’t know that that was the correct answer,” he said. “Protest is a very, very real thing, but for me, it’s much more private.”

That perceived detachment has drawn criticism. When Between the World and Me was published, West took issue with Morrison’s comparison of Coates and Baldwin, and expressed as much in a Facebook post, writing that, unlike Coates: “Baldwin’s painful self-examination led to collective action and a focus on social movements.” In his view, Coates’ inattention to the Black Lives Matter movement and political activists in Between the World and Me “shows a certain distance” from his subject matter.

Coates counters that he hopes he writes “things that clarify stuff for people that go to those marches, that clarify things that inspire people who go and think about policy. I necessarily need a little bit of distance.”

The National Book Award-winning author Jesmyn Ward, who edited The Fire This Time: A New Generation Speaks About Race last year, had a similar response: “Writers use the weapons that they have at hand,” she said, “and though I know that there are many writers that do attend protests – I’ve attended protests in my time – perhaps Ta-Nehisi feels that his most powerful weapon and his most appropriate weapon is his voice.”

There has been criticism, also, of the conspicuous absence of women’s experiences in Coates’ work. In a review of Between the World and Me, Buzzfeed’s Shani O Hilton wrote: “Black womanhood in real life isn’t – as it largely is in Between the World and Me – about beating and loving and mourning black men.” She lamented that Coates’ book, which is specifically about the lives of black males, “is one that many readers will use to define blackness”.

It’s a position that Coates has seriously considered, but he said that the book focused on black male life because “it was the story I had”. He’d been mulling for years over the death of his friend, Prince Jones, a black man, and the decision to address the book to his son necessarily skewed its perspective. Ultimately, he said, “we just need more books”.

Yet Coates’ work has resonated deeply. In a telephone conversation, Painter said that his vision of the United States was congruent with her own. “I think the education that he gave himself – his upbringing and his reading as a student; his reading since that time – all of that has given him a really solid intellectual basis for what he’s talking about.”

Chris Jackson, Coates’ longtime editor and the publisher of One World, an imprint of Random House, said that Coates’ curiosity is “matched with a kind of obsessiveness”.

“He would read 1,000 books about the Civil War. He would talk to every scholar,” he said. “He’d read novels and slave narratives. Then, at a certain point, he started to synthesise all this information into some conclusions about, ‘What does this mean?’”

In 2015, just before Between the World and Me was published and became a sensation, Coates and his family moved to Paris. He experienced the frenzy surrounding his book “through a filter,” and the presidential election from a distance. He noted a “clear difference” between how his blackness was perceived in Paris; there, his Americanness was the most conspicuous part of his identity. Coates laughs off the parallel to Baldwin’s time in Paris, saying that the move was his wife’s idea and “not at all” inspired by the famed intellectual’s experiences.

He returned to the United States last year, ill-prepared for his newfound celebrity. He started to receive invitations to “secret rich people meetings”. He was offered opportunities unrelated to his work as a journalist: to direct music videos (which he turned down) and write comic books and screenplays (which he accepted). His appearances became spectacles, and he found it strange for people to clap for him when he walked into a room.

“I can tell you with a fair degree of certainty that Ta-Nehisi never wanted to be famous,” said Cobb, who has known Coates for more than two decades. “And I think it’s been difficult for him, because you want to have people engage with you and engage your work, but it’s also put a huge target on his back.”

During our conversation, Coates said: “What I have to accept is that I’m a part of it now.” He added: “Nobody thinks, ‘He’s from West Baltimore.’ Nobody thinks, ‘He dropped out of school.’ Nobody sees that anymore.”

As to what he plans to do next, Coates mentions his continued collaboration with Marvel Comics on the Black Panther comic book series, which “satisfies the kid in me” and is “the place where I can go to do something that sort of feels private again”. He was tapped to write a screenplay called Wrong Answer, which will be directed by Ryan Coogler and is based on the standardised test cheating scandal that occurred in Atlanta public schools from 2005 to 2012.

He is also working on a novel, due by the end of the year. The project is tightly under wraps, though his editor, Jackson, described it as “historical” with “elements of the fantastical” and Coates said it deals with race.

He has plans to return to Paris as much as he can, but when asked if he would ever stay, he says: “No, I can’t. The war is here. The war is right here.”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments