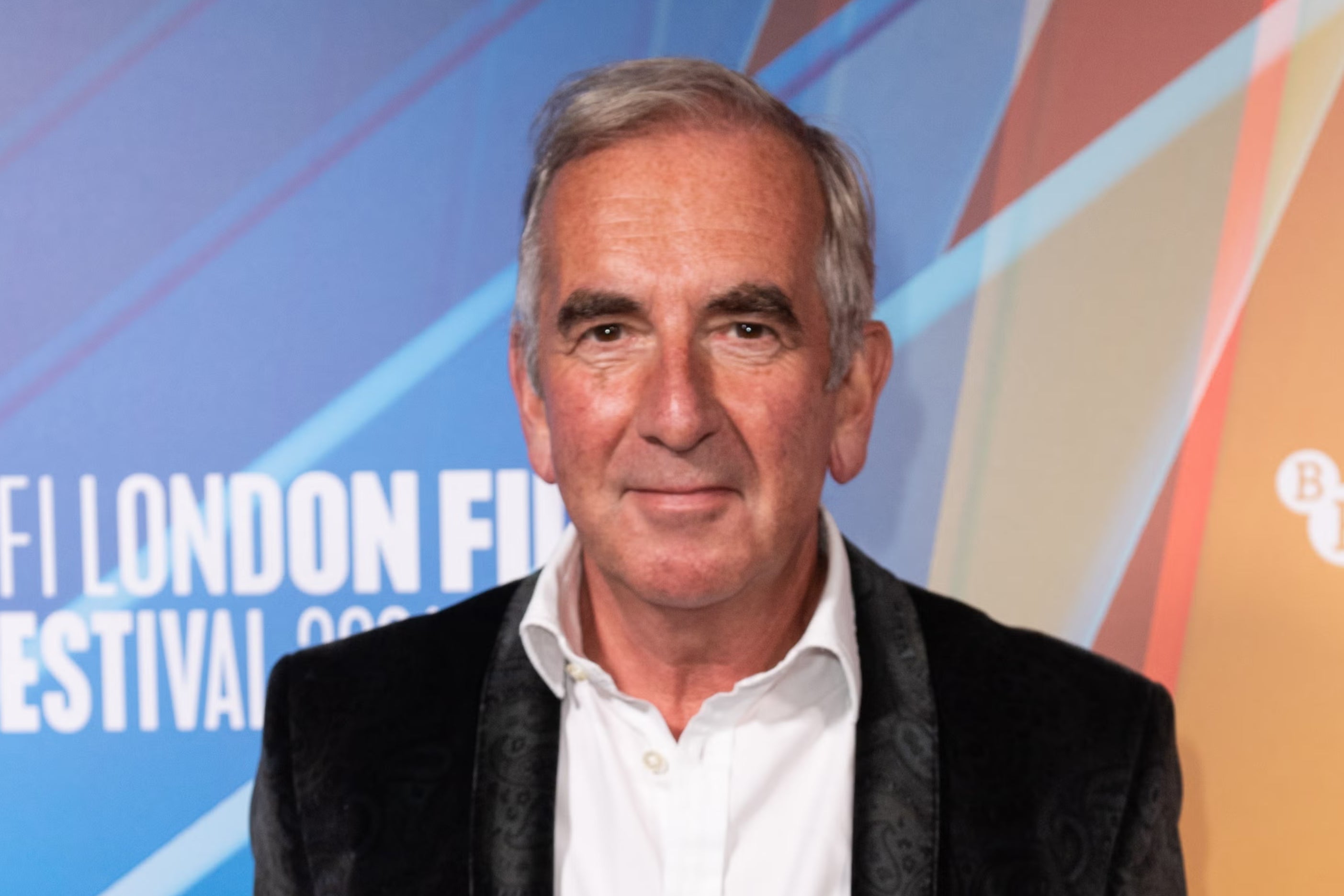

Novelist Robert Harris tells Henley Literary Festival that 20th-century politicians in love had it easier

Robert Harris discussed his latest novel Precipice at the festival on Sunday

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Novelist Robert Harris said 20th-century politicians in love and wanting to conduct affairs had it easier than today, in a talk at the Henley Literary Festival.

Harris discussed his latest book, Precipice, during a wide-ranging discussion at the event in Henley-upon-Thames, Oxfordshire, at which The Independent is the festival’s exclusive news partner for the second year in a row.

The novel follows the intense love affair between prime minister HH Asquith, who was in office as the First World War broke out, and vivacious socialite Venetia Stanley.

Using over 500 letters from Asquith to Venetia, Harris writes the story of their extraordinary affair, encompassing a deeply emotional, and almost certainly physical, relationship - in which some of the state’s most important secrets were shared.

But how did Asquith carry out this secret, extramarital affair whilst under the level of speculation a wartime prime minister would expect?

Speaking to an audience on Sunday, Harris noted that this was enabled by Asquith’s ability to largely go about his life unrecognised, unlike the leaders of today’s governments.

“Several times in the book he does actually meet Venetia,” he said. “On one occasion he goes away for four days, catching the train on his own in October 1914 to Macclesfield and then changing to the Alderley Edge train without a private secretary or police bodyguard.

“So he could get away with things that a modern prime minister couldn’t, simply because he passed unrecognised.”

Harris added: “Also because I think there was much more of an understanding that certain things took place and one didn’t necessarily talk about them.”

He went on to describe the many society children who were not raised by their biological fathers as a result of these 20th-century affairs. Also common in these relationships, and perhaps in Asquith and Venetia’s case, was “corridor creeping” or escaping to the country for a weekend to pursue each other.

Harris also told the Henley audience that Asquith’s car, in which the pair would take 90-minute drives every week, played a key role in concealing their affair.

“Most historians have not bothered about the car. If you say their main point of contact was to drive out from Westminster to Henley with a chauffeur you would think they were just driving,” he said.

But when Harris looked up Asquith’s black Napier 1908, six-cylinder, 45 horsepower vehicle, it soon became clear to him that this was not the case.

“The passengers were separated from the driver by a fixed glass screen with a curtain and communications between the passengers and the driver was by a push button console that lit up on the dashboard,” he said.

“There were blinds on all the other windows. So, from the moment you saw this car you saw that you could have quite a healthy physical relationship inside it.”

The couple’s physical connection came alongside their strong emotional bond, illustrated by Asquith’s need to confide every detail of his life in Venetia.

The prime minister sent her confidential cabinet papers and even wrote to her during critical meetings with Winston Churchill discussing military plans.

Harris said Asquith confided in Venetia simply because he “wanted her view on everything” as he was “utterly besotted” with her.

Harris said: “In this mix Venetia is important. Love is important.

“We think of our leaders as some kind of remote, platonic, ideal figures but they’re flesh and blood. I mean thank God, in a way. I think Asquith was brilliant, utterly dominant in the government but then increasingly distracted by Venetia.”

Venetia eventually broke off their affair in May 1915 and within 48 hours of receiving her letter, Asquith’s government was collapsing.

Upon leaving office in December 1916, Asquith burned all of the letters Venetia had written to him, leaving Harris to do the testing job of imagining her words to the prime minister. A challenge he rises to by referring to accounts of her character told by friends and her granddaughter, whom assisted Harris with the novel.

Henley Literary Festival continues until 6 October. ‘Precipice’ is out now, published by Hutchinson Heinemann.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments