Wounded Tiger: A history of Cricket in Pakistan by Peter Oborne, book review

Pakistan's passions have often played out through their love of the gentleman's game, as a penetrating sports history reveals

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Palestinian literary theorist Edward Said noted that western writers are able to come to terms with the east only through stereotypes. Thus was it the fate of Pakistani cricket to be defined by negative images, and its cricketers to emerge as caricatures.

Despite their records as players and leaders, Javed Miandad was portrayed as a hooligan, and AH Kardar, their first captain, as a fanatic. The country's cricket and its players are far richer and more varied than this pigeon-holing would suggest. And, ironically, it has taken a western writer to restore the balance.

The paucity of imagination when dealing with these fine cricketers contrasts sharply with the imagination that formed them. Imran Khan once told me "We don't come through the system because we don't have a system." The stories of greenhorns catapulted into international cricket are not matched anywhere else. There is a system, it is just that the rest of the world does not understand it. Even today, the terms associated with Pakistan include "ball tampering", "match fixing", "dodgy umpiring" and Ian Botham's recommendation for a mother-in-law's holiday. Seldom is all this countered by the cricketers' remarkable technical inventiveness and sheer joy of playing.

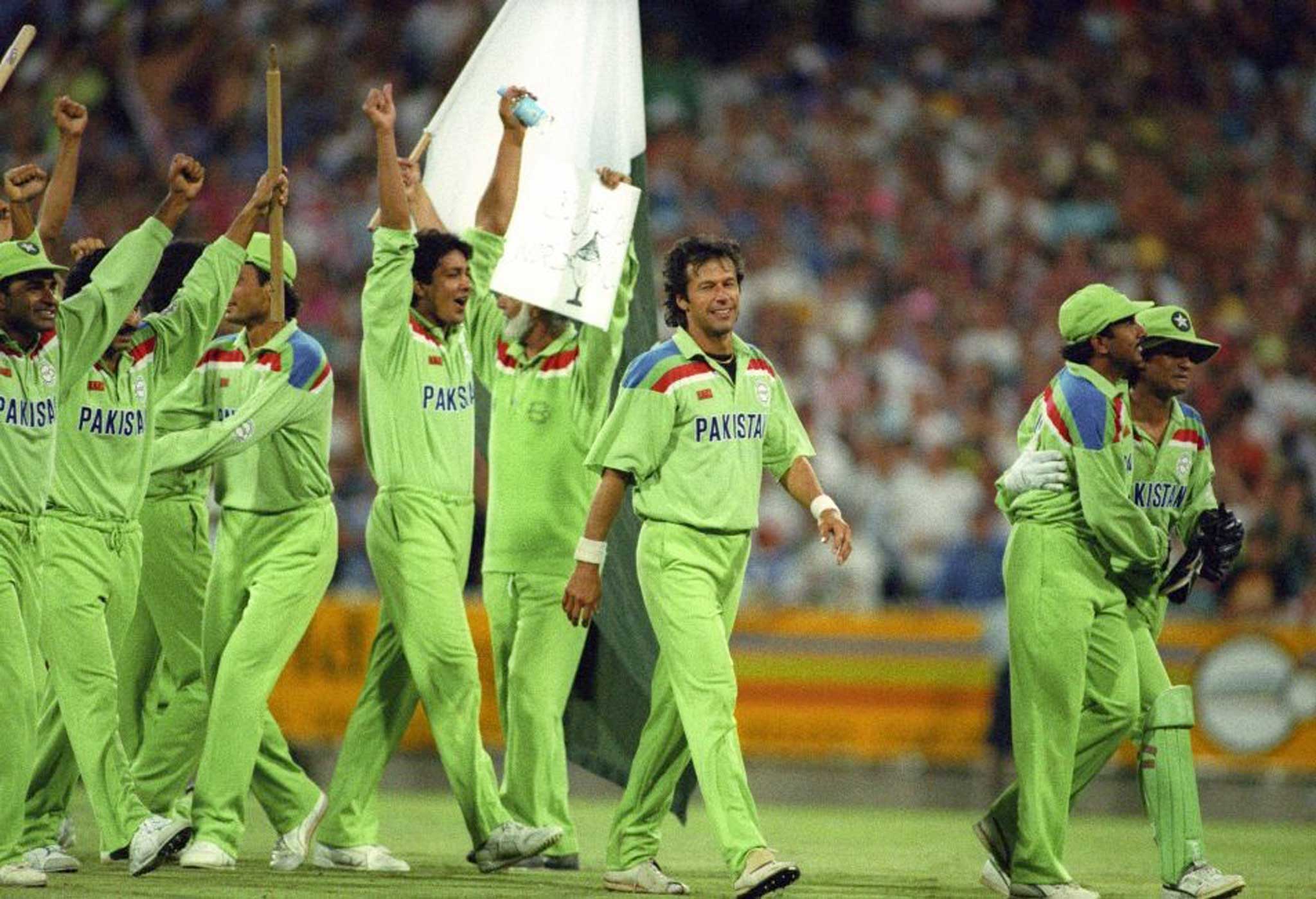

In Wounded Tiger, a variation on Imran's rallying call before the 1992 World Cup which Pakistan won ("We should go out there and fight like cornered tigers"), Peter Oborne brings to the task the sensitivity he displayed in his book on Basil D'Oliveira. This is the most complete, best researched, roses-and-thorns history of cricket in Pakistan. The author places the cricket in its cultural and political context, detailing the series played, the personalities who shone (or didn't), and the decisions that mattered.

"Cricket", he says, "came to fill the same role in Pakistan society as football does in Brazil. It represented, in an untrammelled way, the national personality. A new generation emerged (in the 1970s) which played the game with a compelling and instinctive genius. Many of these new players came from poor backgrounds, and some from remote areas….they imposed their own personalities, with the result that cricket went through a period of inventiveness and brilliance comparable to the so-called Golden Age before World War One."

Both reverse swing and the "doosra" are Pakistani inventions. That it was the medium pacer Sarfraz Nawaz who developed the former is well established, and so is that Saqlain Mushtaq was the father of the latter. Oborne shakes that latter certainty, however, suggesting it may have been a left arm spinner, Prince Aslam, who first bowled the doosra in the 1950s. Keith Miller thought Aslam was the best bowler of his type in Pakistan, but he fell foul of Kardar, the martinet.

Kardar was, in some senses, the creator of Pakistan cricket, the captain who led the team to a win in England on their first tour in 1954. A generation later came Imran in his role as preserver and inspiration to another set of imaginative fast bowlers and spinners, the Wasim Akrams, the Waqar Younuses and Abdul Qadirs. The destroyer, to complete the analogy, is probably the politician who has ensured that this talented side gets no international game at home. This is, as Oborne puts it, Pakistan's age of isolation following the terrorist attack on Sri Lanka's team bus in 2009.

Oxonian Kardar took great pride in dressing like an English gentleman, but as he became more confident, "he acquired a post-colonial sensibility." The English way of running the game no longer appealed. This conversion had consequences for Pakistani cricket, which began to focus inwardly. It learnt to run before it could walk – playing Test cricket before there was a domestic structure in place. Kardar's conversion might also have been helped by the English treatment of Idris Baig, a Test umpire kidnapped by England skipper Donald Carr and some teammates and given the "water treatment" in a room on a tour of Pakistan (he was made to sit and two buckets of water were thrown at him).

The details of that unsavoury incident, which might have got a team banned today, are here for the first time. Baig made some bad decisions, and the English had a problem with his personality, but this was ridiculous. "Carr's team," says Oborne, "like many England sides to follow, was locked into too narrow a set of social and moral parameters to be able to fully respond to Pakistan." At the end of it all, it is Baig who emerges with dignity; when he met Carr many years later he greeted him with a warm hug.

The story of Pakistani cricket calls for vivid colours and bold brush strokes. Record-keeping is not one of the strengths in a country where a player like Alimuddin is seen to have played first class cricket at the age of 12. Any writer must necessarily take in the oral history and the legends that grow with every telling if he is to present a full picture. Oborne focuses on the historical, but does not ignore the anecdotal. The footnotes provide excellent reading, especially the one on Pakistan President Iskandar Mirza, who "fled penniless to Britain, where he is said to have lived in a small west London flat and worked as an accountant at Veerasami, the Indian restaurant in Piccadilly."

What makes Pakistani cricket tick? Many of their teams have taken to the field with no player on talking terms with any other. Miandad and Imran were at loggerheads when they batted together to ensure their World Cup win in Australia, 1992. Once two different sets of players turned up for a Test match at home. Yet it has all somehow worked out. Oborne tells us how.

Suresh Menon is editor of the 'Wisden India Almanack'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments