Who Was Jacques Derrida? An Intellectual Biography, By David Mikics

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

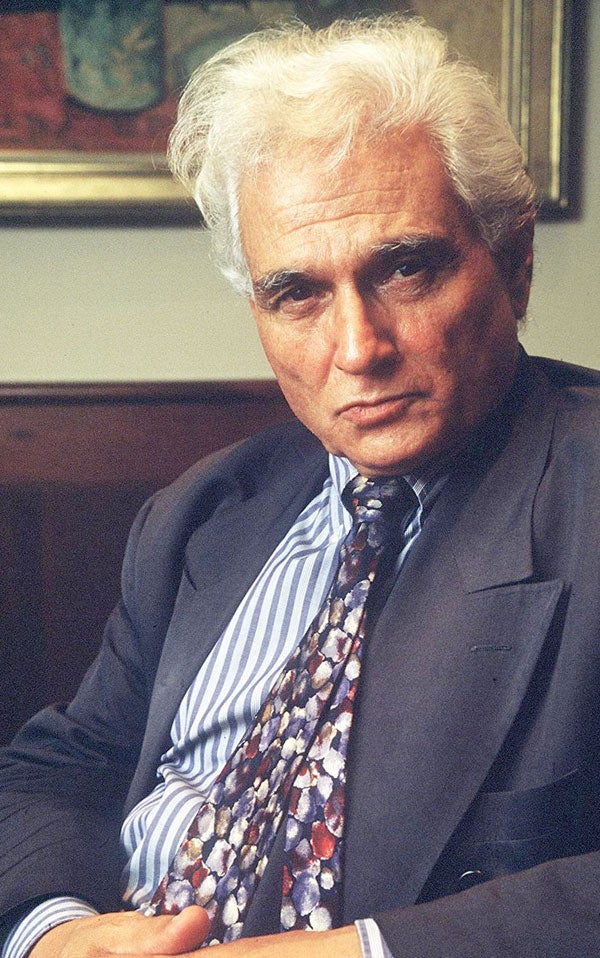

Your support makes all the difference.Since his death in 2004, it's fair to say that the reputation of Jacques Derrida has been in a slow but steady decline. This much has been to the delight of his critics (mainly British or American), who during his lifetime regarded him as a fraud and a charlatan or, worse still, a kind of guru figure whose only creed was a relentless carping nihilism. By the same token, Derrida's critics will argue that there is also something slightly dated and faded about "deconstructionism", the philosophical school Derrida allegedly founded. The accepted wisdom is that these days this pseudo-philosophy persists only in modish new universities where professors of media or cultural studies have run out things to say about Marxism.

The long-standing antagonism to Derrida in the English-speaking world came to a head with the so-called "Cambridge Affair" of 1992. This controversy was triggered by the decision of University of Cambridge to award Derrida an honorary doctorate. This was fiercely opposed by conservative philosophers in Cambridge and across the world. An open letter was even published in The Times, signed by 19 leading philosophers, denouncing Derrida for his "tricks and gimmicks" and having reduced "contemporary French philosophy to an object of ridicule".

Derrida was awarded his doctorate. But despite his show of public indifference, he was wounded by this attack. For all his wayward tactics, as David Mikics explains with great care and lucidity in this admirable book, Derrida was a committed, serious thinker whose main ambition was to make philosophy important outside the philosophy departments of universities. More to the point, Mikics insists that "deconstructionism" (a word Derrida scorned) is not really a philosophical position at all but rather a technique: it is a way of decoding the surface of reality in order to better reshape it.

Derrida himself regarded his critical ways of reading as intensely political. Little wonder then in his later years that he returned to Marx. Derrida's last great book is indeed a series of essays called Specters of Marx, written in 1994 partly as a response to the collapse of Communism but also "to rescue Marx" from the wreckage of history. Derrida reads Marx not as a prophet but as a critic of ideas. For Derrida, this is not nostalgia but a way of preserving Marx.

In the contemporary world of rogue states, phony democracies, the tyranny of technology and the collapsing financial systems, Marx emerges for Derrida as an "ideal" of justice and liberty. Mikics is unconvinced by this and describes Derrida here as "doom-mongering". In fact reading Specters of Marx now is bracing and salutary - not words usually associated with Derrida.

However, the great merit of this intellectual biography is that it not only arrests the downward motion of Derrida's influence but restores him to his proper place. This is as part of a long tradition in Continental Philosophy which connects an ironic scepticism with a profound sense of inquiry. Derrida's peers, the argument follows, are not only Barthes, Deleuze, Foucault, but also Nietzsche, Rousseau or even Plato - all philosophers of what it means to be human as defined through language. Mikics is a literary critic by training and able to explain with forensic detail even the most apparently obscure thoughts of Derrida. The notion of "différance" - which is in my experience a notorious stumbling-block for even the sharpest of undergraduate minds - is explained briskly as the gap between what a person speaks or writes and how that discourse is understood by its audience. The emphasis is on the gap and not the reception (which is irrelevant). Once this point is grasped, great chunks of Derrida's writing suddenly become both comprehensible and stimulating.

Derrida himself argued vehemently that biography was the enemy of truth. His most famous maxim, known even by those who have never read him, is "il n'y a pas de hors texte" ("there is nothing beyond the text"), meaning that an author's words have no relation to an author's life. This is the kind of statement that has always so outraged Anglo-Saxon empiricists.

Mikics takes this statement head-on as a challenge and charges straight into Derrida's education and background in Algeria. Derrida came from a family of Sephardic Jews and was always ill-at-ease with his position as French citizen born into a Muslim country. Hitler's rise to power was celebrated by anti-Semitic mobs in Algiers and Constantine. During the Second World War, the Vichy government persecuted Jews in Algeria as in France with a viciousness that sometimes shocked the Nazis. His experiences as a child left him with the knowledge he was an outsider to French culture even though French was his native tongue.

For Mikics, this is the key to understanding Derrida - as a rebel against all orthodoxies of language or thought. This does not make him a hero. Indeed, Mikics makes the point in his conclusion that Derrida was often wrong, sometimes confused, and satirised his own reputation as a guru. But as this book winningly reveals, Derrida was - as they say in French – "un homme sérieux" after all.

Andrew Hussey is dean of the University of London Institute in Paris

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments