Who Cooked Adam Smith's dinner? by Katrine Marcal - book review: Behind every great man is his mother

In short: all our problems are to be blamed on greedy, self-interested men

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

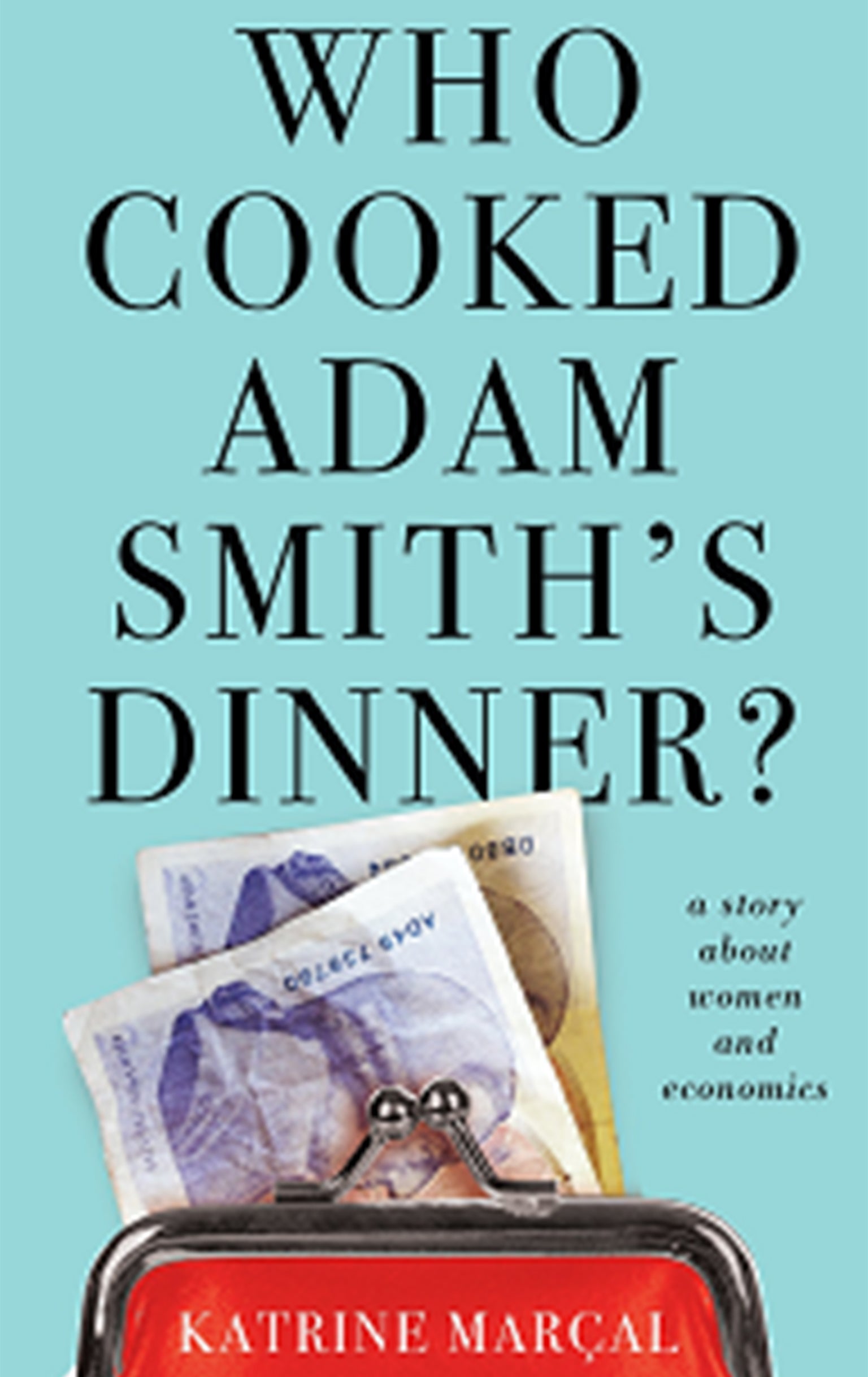

Your support makes all the difference.I laughed out loud over the title of this book by the Swedish journalist, Katrine Marçal: Who Cooked Adam Smith’s Dinner? It’s an absurd but funny question and, you’ve guessed it, the answer is his mother.

Marçal tells you this straight away but what she doesn’t do until the epilogue is explain how Mrs Smith came to be head chef. This is a mistake because the story of why Margaret Douglas, a Scottish noblewoman whose husband died before her baby boy was born, came to care for her adult son tells you more about changes to our society than the rest of the book.

Mrs Smith was 28 when she was widowed. She never remarried and, because her son inherited the estate, was dependent on him for her living. But, in turn, the great economist, the man considered the father of modern classical economic theory, depended on his mother. Since Smith never married, his mother looked after him, cooking his dinners as well as being a huge supporter of his studies.

Yet Marçal uses the Smith household to have a dig at the economist’s famous claim that rational self-interest, and competition, lead to economic prosperity: “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the banker, that we can expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.”

In other words, Marçal reckons Smith got free dinners while his mother was the unpaid slave. Indeed, her motive for writing the book is to debunk the myth of Rational Man, one she claims starts with Smith and ends with the 2008 Great Crash. In short: all our problems are to be blamed on greedy, self-interested men.

It’s the work of women that Marçal wants us to appreciate. Work done out of love and not for money. But for someone who puts Smith so squarely in the dock, Marçal doesn’t go into enough detail on his explanation for the social benefits resulting from the actions of individuals. She forgets too that self-interest works both ways: for centuries women have run the home but in return they ate the meat that their men hunted. Wasn’t that rational too? She also ignores the fact that – despite bad Rational Man – more people live better and longer lives today than at any time in history.

The book asks tart questions, but not the most pertinent one: who would be cooking Smith’s dinner today? If Mrs Smith were alive now, I bet she would have bought her son a microwave and ready-meals.

Portobello books £12.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments