When The Hills Ask For Your Blood by David Belton, book review: One man's return on eve of 20th anniversary of Rwandan genocide

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Of the Rwandan genocide the writer Uwem Akpan said: "If I can begin to understand, I may have to see how one person was killed... and if I hear someone sacrificed her life for another person I try to work out in my mind how this is possible." Akpan turned to fiction. "My Parents' Bedroom" is the story of a young girl whose Hutu father kills her Tutsi mother.

David Belton, a BBC producer, was witness to the genocide and its aftermath and has, it seems, been trying to work out how it became possible ever since. In 2002 Belton co-wrote and produced the feature film Shooting Dogs. As we approach the 20th anniversary of the genocide he has written a memoir, When the Hills Ask for Your Blood. Akpan's choice of words is helpful and telling. For neither writer presumes that the individual motivations of the killers of one million Rwandan Tutsis will ever be understood. Instead they reach for something more modest. How did it become possible?

Do you remember where you were the week the news of the genocide broke in April 1994? I do, because I was getting married and going on my honeymoon and so the experience of reading Belton's account of what was happening at the same time in Rwanda was made even more disturbing for encountering familiar dates. On my wedding day several thousand men, women and children were massacred in a church in Nyarubuye in south-east Rwanda.

On my birthday three weeks later, Belton and his crew was forced to stand by whilst a man was hacked to death before their eyes. I remember the news images: rivers choked with swollen bodies, a family sitting slumped in front of their house, their throats slit. I remember the reporters' choice of words: savage, senseless, chaos. Nobody understood. Belton's book demonstrates all the shortcomings of journalism. There has long been, on the part of the Western media, a tendency to strip African wars of their political complexities, a tiresome essentialism which more or less says: "well, what do you expect?" Belton excavates the truth and layers the political, social and military dimensions of the conflict onto three peoples' stories, to produce a book that is both illuminating and profoundly moving.

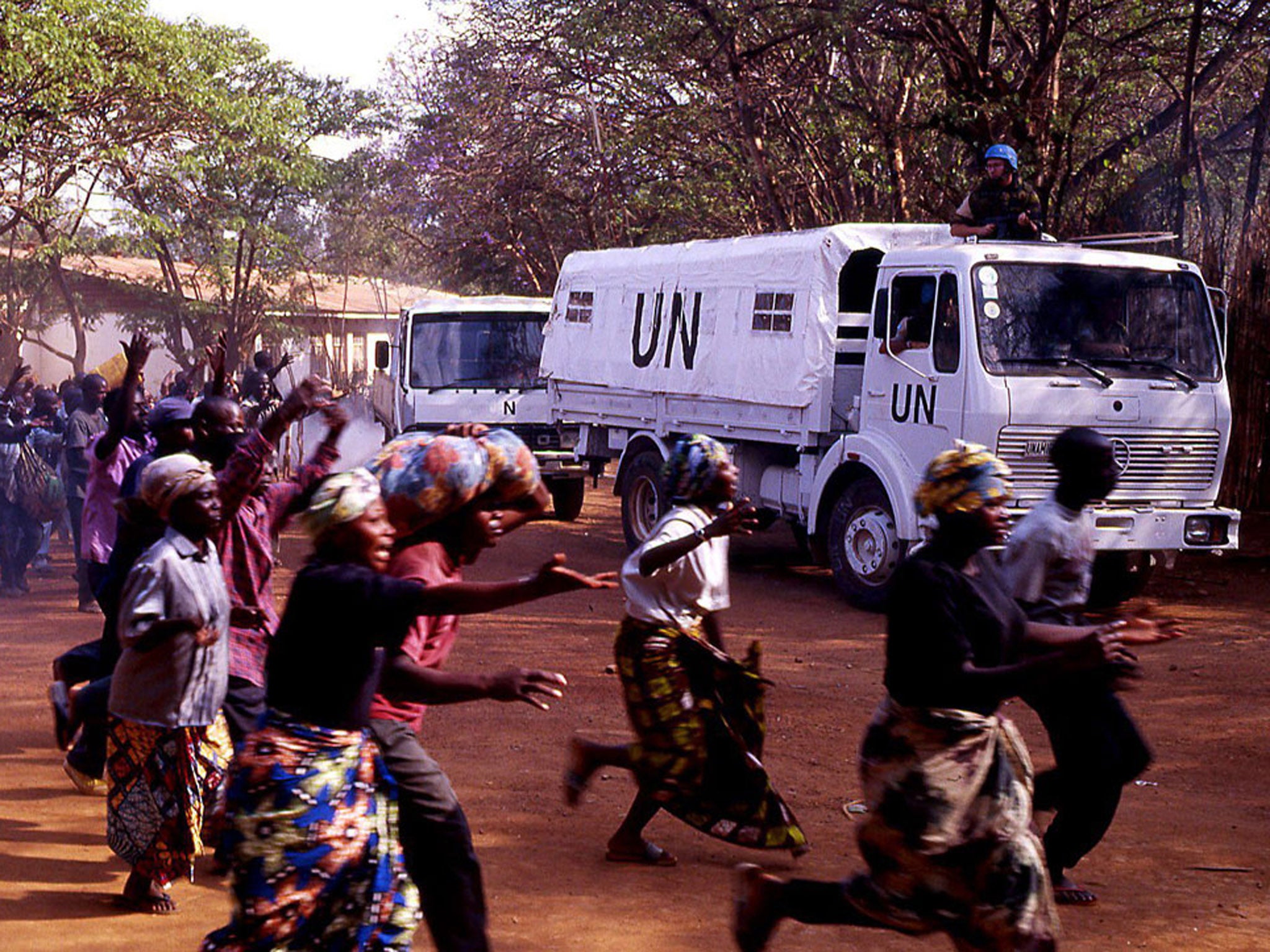

On 6 April 1994, President Juvenal Habyarimana was assassinated. By then the Rwandan government had been at war with the Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Front for four years. Immediately after the assassinations, hundreds of prominent liberal Hutus and Tutsis were killed. A few days later, a pre-planned campaign by Hutu extremists to murder all Tutsis was enacted. Jean Pierre Sagahutu (his surname means "not a Hutu"), his wife Odette and a Bosnian missionary priest Vjeko Curic were swept up in the subsequent blood-letting. Unable to reach home, Jean Pierre is hidden in a disused cesspit by a friend.

Odette with their two children joins the march of refugees. Curic saves thousands of Tutsis by ferrying food to those holed up in the church grounds and smuggling others out of the country. By switching between their stories and later his own arrival in Rwanda, Belton ramps up the tension, forcing the reader to walk the walk with Odette, the awfulness of waiting with Jean Pierre. You know they survive, there wouldn't be a book without them, but you wonder how they could possibly have succeeded. What Belton so successfully captures is not so much the nature of war, but the nature of fear. At night, Jean Pierre hears the killers going from house to house, they have lists of names, they work through them methodically; when they're tired of killing, they rest. And then they come back.

So how was it possible? One reason was that Rwanda was administratively highly organised, split into communes, secteurs, cellules and finally households. Each commune was headed by a bourgmestre who held the names of the people in each cellules. These bourgmestres were co-opted or forced into taking part. The second reason was that the genocide had been four years in the planning. Hutu extremists recruited followers from Rwanda's tens of thousands of unemployed, resentful young men. The extremists and their henchmen began the work, the rest of the population went along with it or stood by.

Civil war gives vent to petty rivalries, long-standing resentments. Jean-Pierre's father was killed by a jealous colleague. Those who opposed it (and there were plenty of Hutus who did) became targets themselves. It's a tried-and-tested recipe for mass slaughter from Nazi Germany to the former Yugoslavia, whose war was contemporaneous with that in Rwanda. In fact, given the priest Curic's background, I would have liked to hear more about Bosnia versus Rwanda, but oddly this comparison, so ripe for examination, is barely explored.

Belton returns to Rwanda in 2004 and then again in 2012/13. The aftermath of the war is equally, differently fascinating. Thousands of Hutu prisoners literally rot away in prisons designed to hold a few hundred. Without room to sit, let alone lie, the men must stand. They die on their feet. Curic, who has remained in the country, sees a man standing on the stumps of his legs. Curic is impatient, sometimes high-handed. His concern for the Hutu prisoners begins to make him unpopular. In the new Rwanda, the words Hutu and Tutsi are banned, at the same time, there are shrines to the Tutsis who died everywhere. In an attempt to bring reconciliation and also empty the prisons, Gacaca trials bring killers face to face with the families of their victims.

Belton tries to fit the pieces together. He struggles with the idea that ethnic identities are banned. A Westerner tells him to use the words "Honda" and "Toyota". The lack of sufficient discussion of the past, the stripping of identity: these things bother him. A young Rwandan woman insists tribes were a colonial imposition. "You've always existed like that," argues Belton. But under the colonials, ethnicity became codified as did race in apartheid South Africa, a basis for the giving and withdrawing of privileges.

South Africa didn't ban the words black and white, but the government certainly encouraged people to see themselves as part of a new South Africa. Germany underwent de-Nazification; to this day the swastika remains outlawed. In that way you can't blame Rwanda, for a country that has lost its way will take many turns to find a route back. Perhaps what recovery really requires is an adjustment of reality, to cease asking how one human being could do such things to another, but to accept that we do and put our energy into preventing it happening again.

Aminatta Forna's latest novel, 'The Hired Man', is published by Bloomsbury

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments