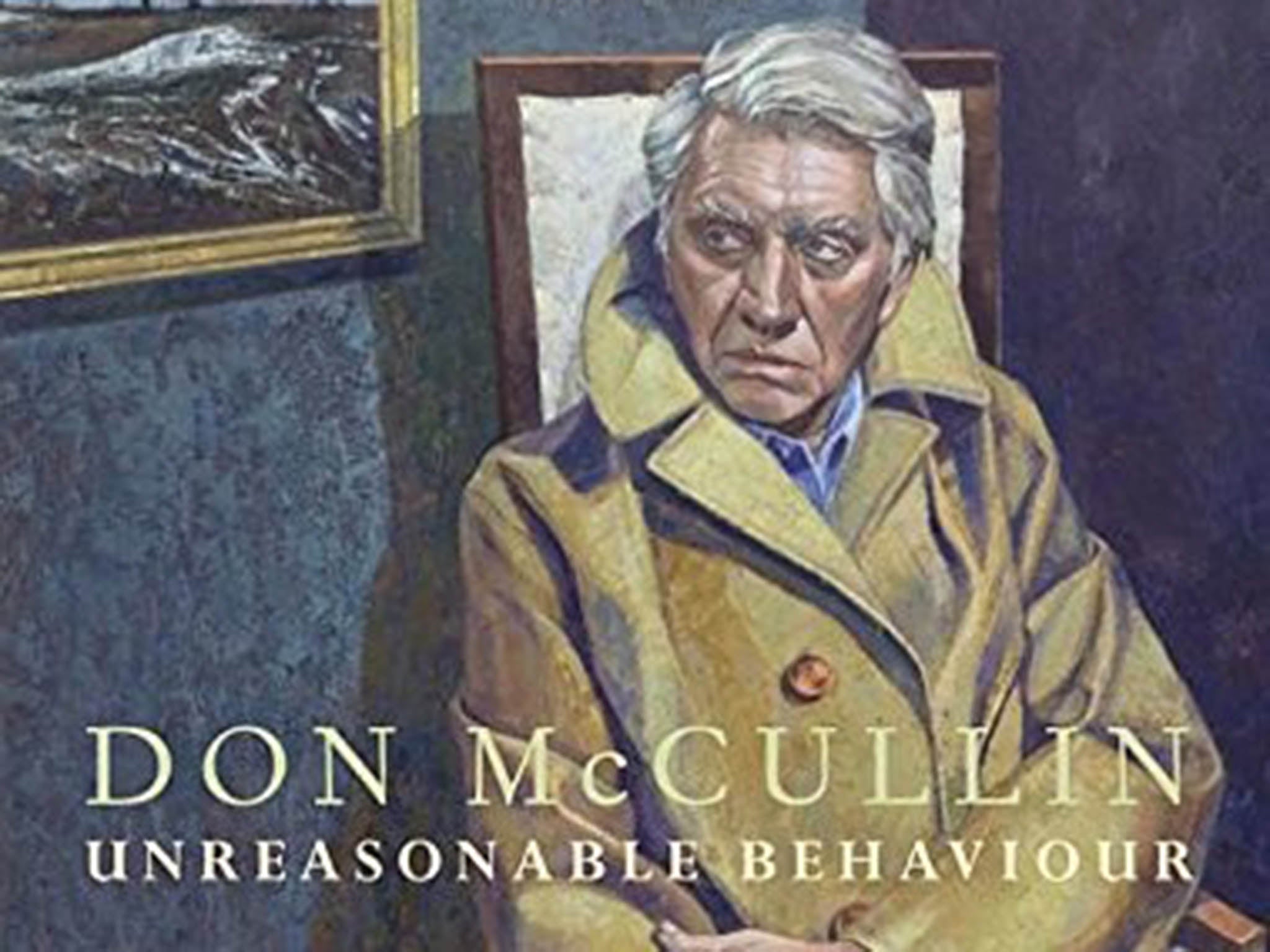

Unreasonable Behaviour, by Don McCullin - book review: McCullin’s self-portait completes his portfolio

In his updated autobiography, McCullin ruefully admits that the body that somehow survived many of the worst hellholes of the latter part of the 20th century is “no longer truly fit for front-line purpose”

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.At the age of 80, the venerated British photojournalist Don McCullin is, by his own admission, “walking around the crater’s edge of the volcano”. In this updated edition of his autobiography – first published 25 years ago – he ruefully admits that the body that somehow survived many of the worst hellholes of the latter part of the 20th century – from the Congo in 1964 to Iraq in 1991 – is “no longer truly fit for front-line purpose”. Even his late-flourishing interest in landscape photography is now threatened by aching feet and arthritic hands.

After declaring himself finished with combat photography in the first edition of the book, the old warhorse reveals he was lured back to the battlefield at the age of 77 despite undergoing a quadruple heart bypass. The late-career foray to the ravaged Syrian city of Aleppo in 2012 was a qualified success. “I experienced one last time that amazing sustained burst of adrenalin … in short I felt very much more alive than I had done before,” he writes. Sadly, the resulting pictures were “undoubtedly below my vintage best …”.

The original edition of Unreasonable Behaviour offered a rather melancholy final chapter. Retired from war photography and frustrated by a flirtation with advertising, McCullin found himself haunted by the ghosts of the tortured souls who have passed in front of his lens. There was guilt too: a struggle to understand why he had emerged relatively unscathed while so many others had died in battle.

The updated book finds him remarried and relishing fatherhood – he has a young son called Max. His world, which revolves around a farmhouse in Somerset, is more reconciled perhaps, but the ghosts are far from vanquished. Now, as it was a quarter of a century ago, the title of the book is multi-faceted. McCullin makes it clear that the act of photographing the most obscene acts of man is inherently unreasonable given that it inevitably extracts a heavy price from those who practice it and the loved ones they leave behind. The toll for this working-class Londoner, who began his journey photographing the gang members he ran with in Blitz-scarred Finsbury Park, includes his first marriage, several relationships, and anguished memories made more vivid by semi-retirement. “The lucky escapes and the cruel encounters and the ghastly injuries I’ve seen keep coming back to me unbidden, sharp and clear as a photograph,” he writes.

Endless accolades and awards have done nothing to assuage his deep seated unease about his profession. I was struck by the contrast between the ambivalence he expresses in Unreasonable Behaviour and the relative certainty shown by another distinguished, albeit younger conflict photographer Lynsey Addario, in her recent memoir It’s What I Do. For Addario war photography is a calling and graphic pictures of carnage have the power to influence governments and individuals.

McCullin, for the most part, seems far less sure. “I take more than I bring. That’s not a role I’m proud of,” he told The Spectator recently and his book is littered with questions about photojournalism as an agency of change. The only certainty – an issue on which both McCullin and Addario agree – is that it can be addictive to the point of self-destruction.

Unreasonable Behaviour, by Don McCullin, Jonathan Cape £25

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments