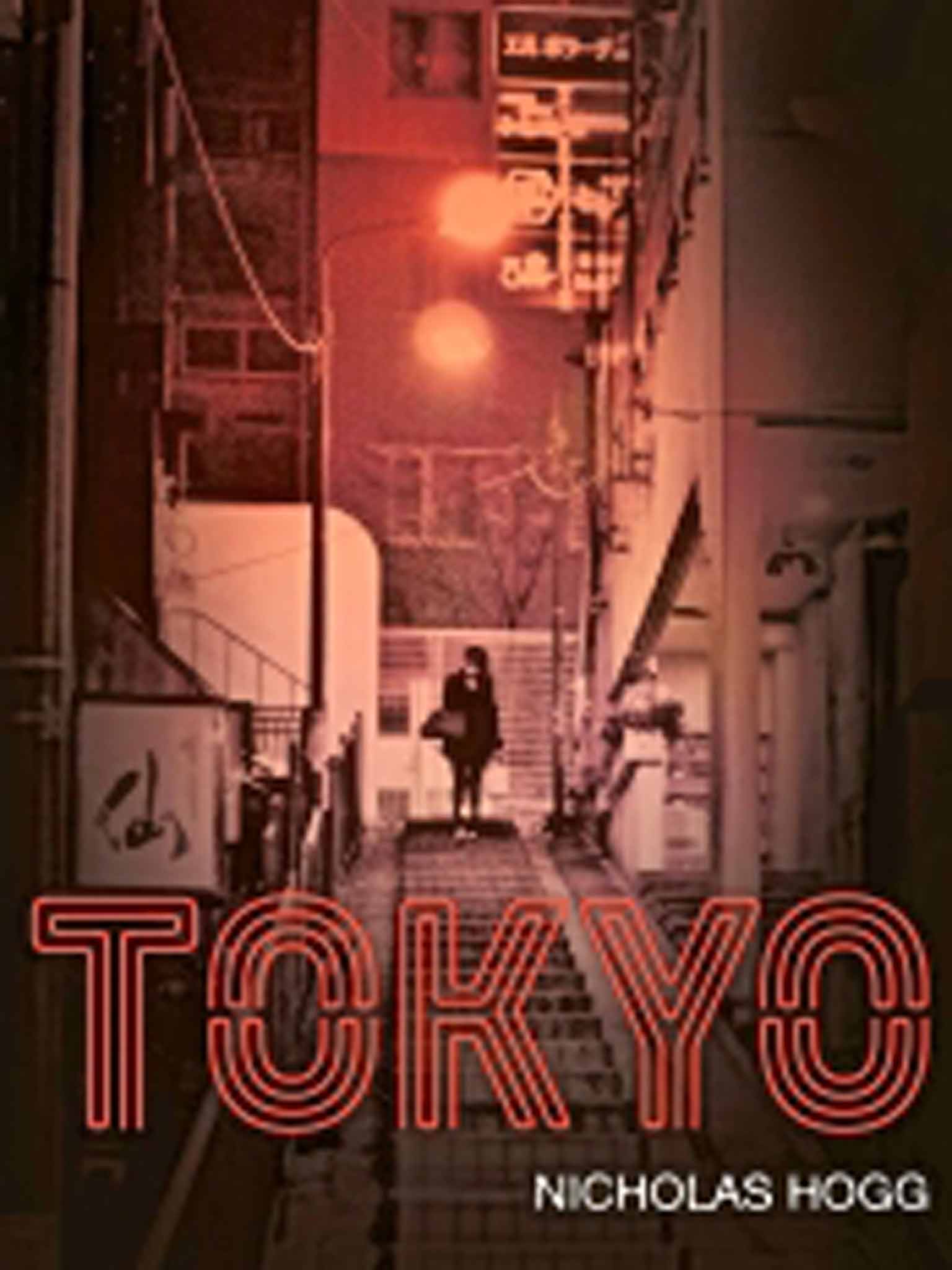

Tokyo By Nicholas Hogg - book review: Too much cliché and backstory in this Japanese noir

A novel with the potential to be more than a travelogue with literary pretensions

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Nicholas Hogg's third novel has all the ingredients of a classic noir. The city of the title is a blur of neon and love hotels; and with much of its culture hidden from view and above street level, to outsiders Tokyo is fascinating, mysterious and menacing.

Protagonist Ben Monroe, a British social psychologist given to introspection, is author of bestselling book "Gangs, Groups and Belonging" and thus also something of a detective of human motivation, particularly in a country long ruled by societal traditions.

Ben, nearly 20 years ago, had been a visitor to "a Japan I knew nothing about beyond the lazy stereotypes". On his return to contemporary Japan he is still a gaijin, bruised and brooding about the failure of his marriage, but able to take the reader on a tour of all things Japanese – nabe feasts and cherry blossom; karaoke and hostess bars.

We kick off with Ben's teenage daughter Mazzy, who is reluctantly en route from LA to Tokyo in order to spend some quality time with her father. On the plane Mazzy sits next to a young Japanese man who tells her a traditional folk tale and then vanishes only to reappear from a different authorial viewpoint, stalking Mazzy as his backstory as a cult member is slowly revealed.

Meanwhile, the bitter history of Ben's marriage breakdown comes to light while his obsession with a previous relationship grows. On his first visit Ben had encountered beautiful – and possibly damned – Kosue while she worked as a hostess in Hiroshima.

We must suppose it's no accident that ex-wife Lydia sends a Geiger counter to Mazzy to chart the toxic danger in post-earthquake, post-Tsunami, post-nuclear accident Japan; a country that is as traumatised as Ben himself. As Ben's quest to discover what might have happened to Kosue leads him to the seedy underbelly of Tokyo's Roppongi – or red light district – so Mazzy's stalker gets ever closer.

Do the ingredients add up to a resolved recipe? Well, with the narrative created mainly from backstory, the plot and characters aren't given a chance to develop. And there are too many romanticised clichés pretending to be people (Ben's mentor Professor Yamada, for example: "Clad in black, with long dark hair falling down his cheeks, he was more Transylvanian fashion designer than fusty lecturer").

Despite some occasionally successful attempts at hard-boiled prose, the writing is too in love with itself to be effective and the result is a victory of surface over meaning, style over substance. It's a shame, because this novel has the potential to be more than the travelogue with literary pretensions that it currently is. When Hogg has a more compelling human drama to tell, then his take on noir will become interesting.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments