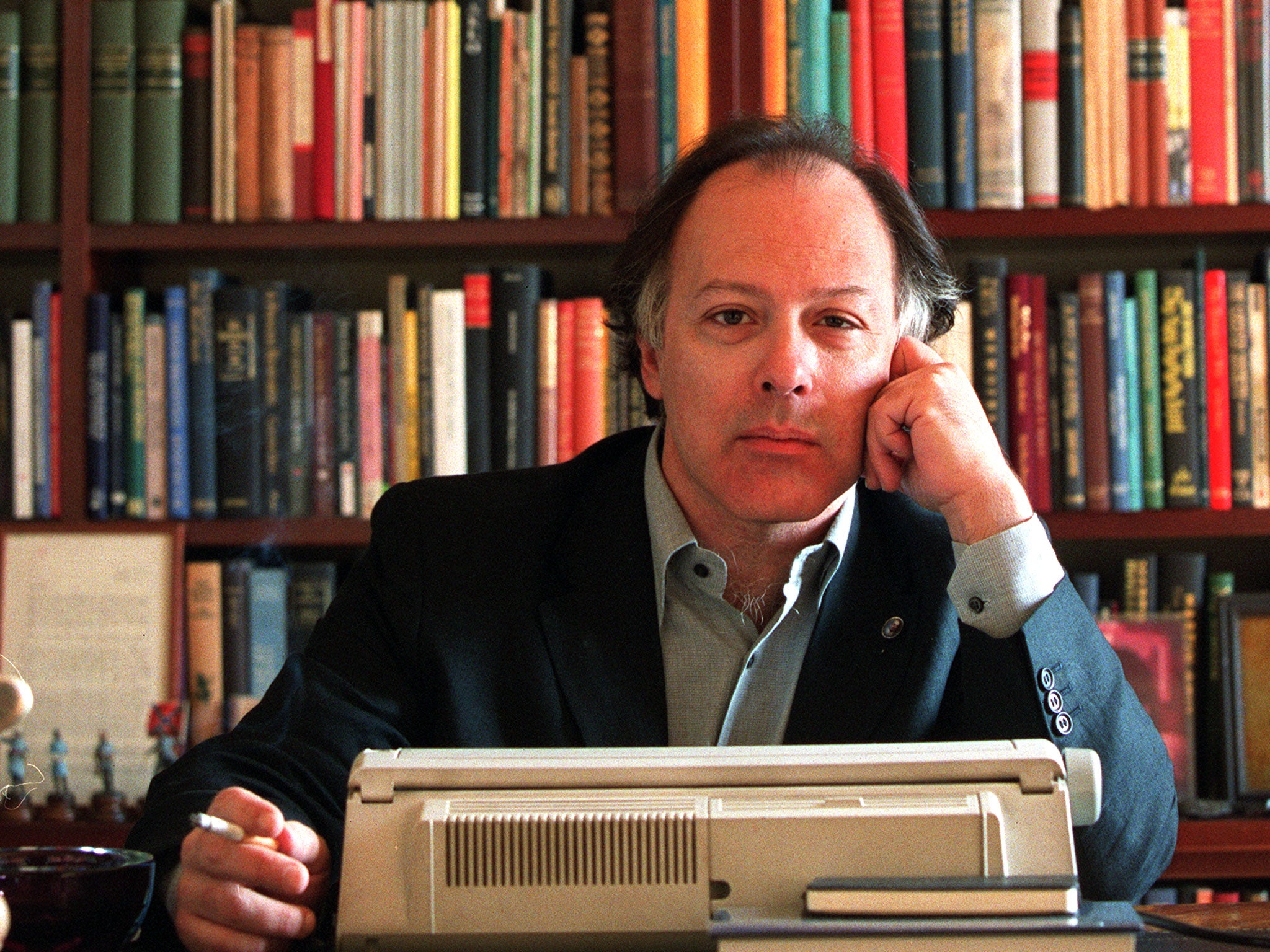

Thus Bad Begins by Javier MarÍas; Trans. by Margaret Jull Costa, book review

Javier Marías’s new novel is full of intrigue, but some longueurs too

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The novels of acclaimed Spanish writer Javier Marías share several commonalities, and his latest, Thus Bad Begins, is no exception. Marías's narrators are intelligent analytic but morally dubious characters, who are cast into the role of spy. His plots involve suicides or murders, and a complex unravelling of secrets. And his style is filled with long digressions, endless clauses and sub-clauses. The action in a Marías novel will, at the most critical moment, halt abruptly as the narrator spends paragraphs, even pages, in philosophical contemplation. The overall effect is something quite marvellous.

Marías's novels are both accessible and literary, pot-boilers that are also lyrical meditations. However, a fine balance is required to achieve such an affect, and Thus Bad Begins falls somewhat short.

In the novel, the narrator, Juan de Vere, recounts his days as a young man in the 1980s when he was tasked by his employer, the film-maker Eduardo Muriel, to spy on a friend who Eduardo suspects of wrong-doing. But Juan finds himself also spying on Eduardo and his wife Beatriz, as he tries to uncover the secret behind their unhappy marriage.

True to Marías form, Juan's propensity to philosophical and analytical inquiry is masterfully depicted. For instance, as he secretly witnesses a moment of tension between Eduardo and Beatriz, Juan embarks on a long rumination on the reciprocity of love, and the precariousness of relationships.

Images such as the lover tremulously choosing the object of their affection, or the indifferent moon that watches over us all, are repeated over and over again. The meanings of these abstract ponderings on love and rejection transform and expand as the story develops, as we learn more of Beatriz, and indeed, Juan himself.

There is, however, another kind of digression in this book that is less successful. This is connected to the central theme of rumours, gossip and secrets. Lengthy sections deal with the power and the danger of a rumour, with the desire to know versus the potential consequences of that knowledge.

The novel self-referentially plays with the reader throughout, withholding and revealing information in a manner that occasionally misfires. For instance, there are several long sections that consist of one character telling another a piece of gossip, sometimes bearing little relevance to the plot, such as when actor Herbert Lom recounts a convoluted scandal involving a film producer, Harry Alan Towers. These characters, like several others in the novel, actually exist in real life, and although there is an interesting play here between fiction and reality, the gossip appears to be more for the amusement of the writer who is familiar with the real-life characters than for the readers' benefit.

By the time the narrator announces he has a secret too (one not "very grave") and tells his readers, "you will all have to keep my secret and be silent too", so many secrets have accumulated, that we, like that complacent moon, begin to feel a little bored. And when Juan delays imparting information to Eduardo, thinking to himself that a "prior period of boredom is vital to awakening curiosity and invention", the reader is unconvinced. Can boredom build up a sense of anticipation? Perhaps in a slimmer novel, or one where the secrets hold more weight. Here, we are left somewhat weary and disengaged.

There is also something dated in the kind of heterosexual voyeurism that Marías's novels abound in: men watching women, obsessing over their voluptuous thighs, high heels and tight skirts. An old-fashioned machismo manifests in a scene where Juan is amazed that a man should feel attracted to a transgender person, and in an incongruous and rather anti-climactic revelation about a character's homosexuality. Still, in spite of these shortcomings, the skill and magic that make up a Javier Marías novel are here, all in place.

Hamish Hamilton, £18.99. Order at £16.99 inc. p&p from the Independent Bookshop

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments