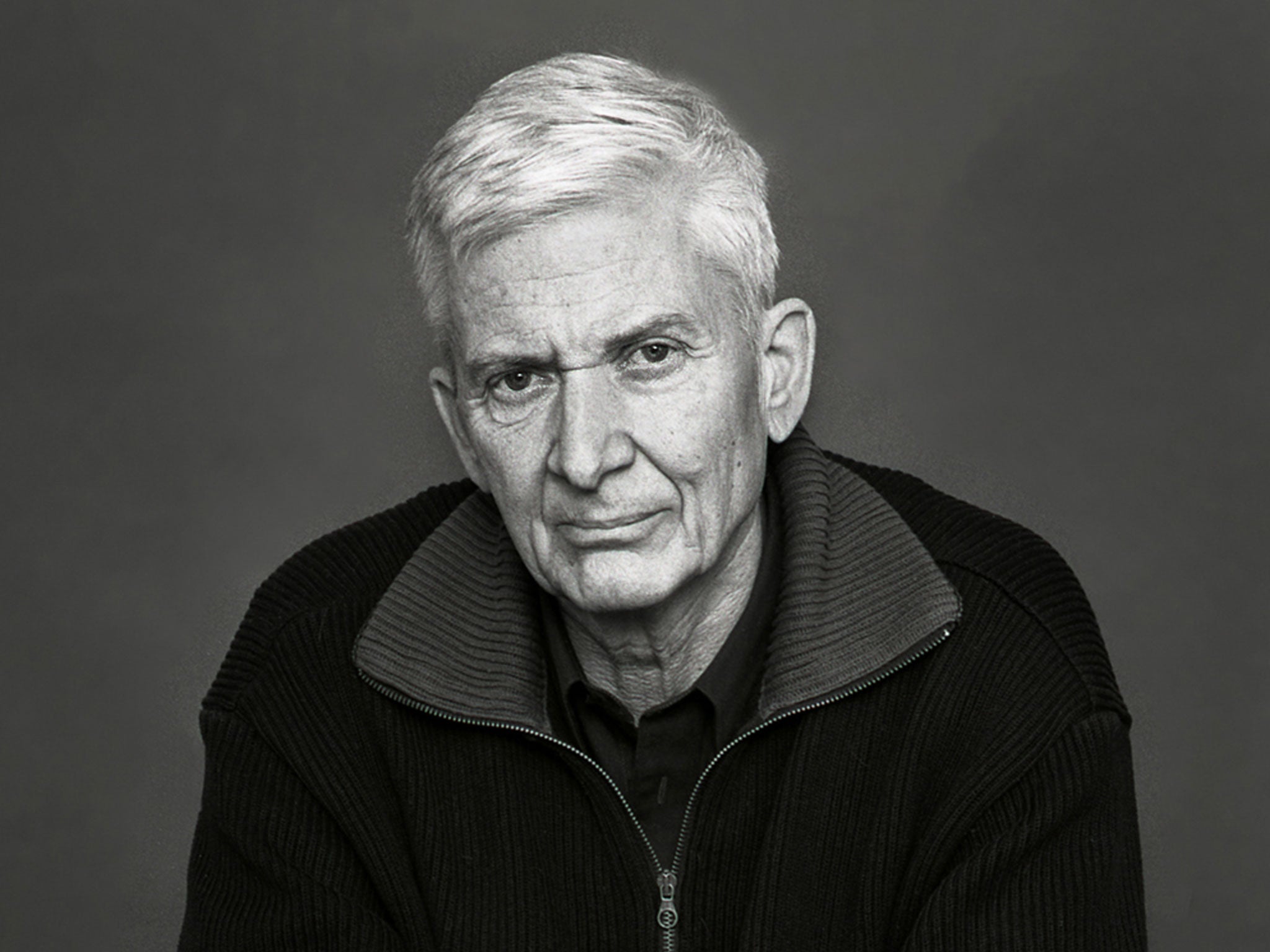

The Wandering Pine by Per Olov Enquist; trans. Deborah Bragan-Turner, book review

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Autobiographical fiction – or is that fictional autobiography – is hot right now thanks largely to Karl Ove Knausgaard's ceaseless delight in the consistency of his children's nappies and the albums he heard as his father hammered at his psyche.

Knausgaard raises his tousled head, almost inevitably, in the blurb of Enquist's The Wandering Pine. Subtitled "My Life as a Novel", it traces a character imaginatively called P O Enquist from a small town in rural Sweden via international success to a dismal, alcohol-fuelled late period.

While there are Knausgaardian glimpses – P O, typing his first novel, dips a comforting toe into his newborn son's crib – Enquist doesn't need an Ove-come-lately to justify his slippery memoir. Revered as a novelist and playwright, he used fiction to dissect real life when Knausgaard was a glint in his father's cold eye. 1968's The Legionnaires was a "documentary novel" that examined Sweden's extradition of Latvian soldiers to Russia after the Second World War.

The Wandering Pine's claims on fiction mirror Enquist's belief that his identity is protean and composed. After a prologue of fractured memories suggestive of the over-arching themes – loss, madness, degradation, and hope of resurrection – the narrative swells towards several dramatic "pivots". These turning points describe falls from states of ever-declining innocence: his father's death, leaving home, an elegiac burst of literary fun culminating in sex and Sgt Pepper.

Enquist's perpetual uncertainty results in lots of questions. The most important are: how did life, having started so well, end up so badly? Where did his addiction to writing come from? Echoing Joyce's A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Kundera's Life is Elsewhere, he finds answers in his upbringing. His birthplace of Hjoggböle is vividly re-imagined as divided between God-fearing (his devout, widowed mother) and godlessness (sport, Flash Gordon, masturbation to mail order catalogues).

One can read P O's adult life as a concerted attempt to resolve the resulting schisms in himself – firstly through art, then politics and finally alcohol. The desperate concluding chapters, in which P O is committed to Scandinavia's answer to AA, expose his contradictions in their antagonistic glory. Defiant but self-destructive, self-aware but self-centred, he is heroic inasmuch as his flaws never quite lose your sympathy. I urged P O to pull out of his tailspin, if only, at times, so he'd stop dissecting the hell of life in a luxurious Paris apartment.

The book's blending of fact and fiction does raise questions. Are we judging the character of P O Enquist, or P O as a character (and is there a distinction)? Is the distance between life and artifice a strategy for Enquist to assess his actions with pitiless clarity or to detach himself from his failings? His narrative teases with gaps, most often in the details of his romantic, sexual and family life. And what are we to make of casual admissions like his baby son is "essential… almost as important as his debut novel"?

The Wandering Pine is a fascinating, if frustrating book that works best when it feels most like a novel – most obviously in its oblique beginning and end. The linear middle which recounts P O's literary researches, his failure on Broadway, and stints in America, Berlin and Paris are interesting in ways that good conventional biography tends to be. And I suspect the last thing P O Enquist ever wants to be is conventional.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments